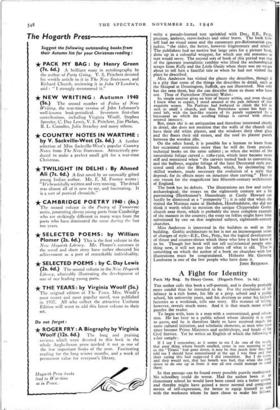

A Fight for Identity Pack My Bag. By Henry Green.

(Hogarth Press. 7s. 6d.) THE author calls this book a self-portrait, and is thereby probably more candid than he intended to be. For the revelation of his infancy in a rich home, his life at a prep. school and a public school, his university years, and his decision to enter his father's factories as a workman, tells one story. His manner of telling, however, reveals much more. And it is that much more which puzzles the reader.

To begin with, here is a man with a conventional, good educa- tion. He has beer to a public school whose identity it is easy to guess, and he is therefore likely to have received much the same cultural initiation, and scholastic elements, as men who have since become Prime Ministers and archbishops, and heads of the Civil Service. Yet he writes an English of which the following Is a fair sample: If I say I remember, as it seems to me I do one of the maids. that poor thing whose breath smelled, come in one morning to tell us the ' Titanic ' had gone down, it may be that much later they had told me I should have remembered at the age I was then and that their saying this had suggested I did remember. But I do know, and they would not, that her breath was bad, that when she knelt down to do one up in front it was all one could manage to stand there.

In that passage can be found every possible puerile inadequacy. No schoolboy could do worse. Had the author been at an elementary school he would have been caned into a better syntax, and thereby might have gained a more normal and competent means of self-expression, the better to equip himself to flux with the workmen whom he later chose to make his fellows. Both in this book, and in his earlier attempts at the art of the novel, I can see no justification for this infantilism. What virtue he shows as a writer—and he shows a lot—emerges in spite of, and not because of, this absurd idiosyncrasy. Perhaps he is aping that school of painters which is already outmoded, who drew profile portraits with two eyes, and still-life studies that were for ever sliding and forever wrong.

If the reader survives the irritation caused by this wilfulness or incompetence, he will discover a personality which is interesting but also puzzling. It is puzzling because, as in his self-expression, the writer has had a life that should have given him an adequate cultural sophistication. But one has a sense, from this book, that the background of the writer's life is bleak and bare, with no riches of scholarship, no historical joy. A few things obsess him; the problem of sex life, the inequalities of wealth and poverty, the technique of good-fellowship and conviviality, and the superstitious fear of death. This last is the motive for the writing of the book. He says openly that he believes this war will destroy him, and that before he is killed he wants to put on record the incomprehensible experience which he calls his life. But he gives the impression that it is incomprehensible not because of its vastness, and the superb antecedence of history and heredity from which it sprang, but because he is naive and clumsy-fingered in the handling of his environment. The result is a certain poverty of texture in the stuff of his narrative, and this in spite of his uncommon sensibility and quick instinct in things which can be apprehended by physical contact. He seems to be deliberately groping his way along a self-destined path that is, after all, running alongside the public way of normal society.

This wilful determination to do and say things without the help of precedent may be due, as he says, to the shock on his childish mind caused by the last war.

But if then one grew up in the forced atmosphere of war under a strain which went on but which did not directly stress one, and as with the opportunities this strain gave to every child to see the cracks in the facade people put up before children in my circumstances, sleeping as I did at home alone and so with less chances to see people at bay, I came to know there was no great difference between ages and to guess that twenty years can go by fast. They can go by so quick the only difference is that at the end one may be far more tired, thinking much the same about everything, only blunted.

Through this execrable maltreatment of English one sees that the author is capable of reaching many vivid half-truths.

RICHARD CHURCH.

Previous page

Previous page