THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Budget Repercussions

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

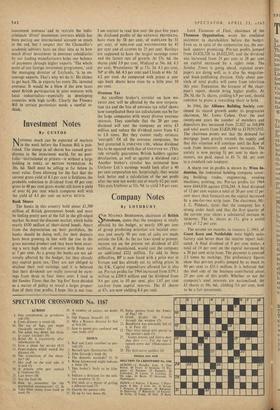

ON April 27 the Finance Bill will be pub- lished, and it behoves all people of good will to stand up for the principles of Mr. Callaghan's budget against those who would destroy it be- cause of the few mistakes committed by the draftsmen. The purpose of the budget was two- fold. It was designed, first, to persuade the workers of this country that, as the taxation system would now strike a fair balance between capital and income—instead of favouring capital as it used to do—they must seriously co-operate in a national incomes policy which they have not yet begun to do. (Remember the fine peroration in Mr. Callaghan's budget speech about uniting a divided nation.) It was designed, secondly, to secure the balance of payments more firmly by restraining and restricting the flow of capital abroad. These are fine principles which must be upheld, but I am sure that Mr. Cal- laghan did not intend that the Bill carrying these principles into action would, on the first count, devalue government credit, demoralise the gilt- edged market, drive up the rate of interest and make our housing and social investment intoler- ably expensive; and, on the second count, militate against our export trade, hand over part of our domestic oil trade to American companies and perhaps worsen our balance of payments in the long run. But there is a distinct possibility that such damaging, untoward effects will follow on the anti-capital fervour of the academic drafts- men of the Finance Bill.

On the first count, the trouble has been caused by bringing the life assurance companies into the capital gains tax, although in all other respects their taxation remains unaltered. This has brought to an end their switching operations in the gilt-edged market, by which they used to add perhaps I per cent to their interest in- come, and destroyed the marvellous flexibility of the open market in £20,000 million of British governnient funds which was the envy of the world. The result has been to demoralise the market, depress prices and raise the rate of in- terest. Of course, the market will recover when Bank rate is reduced to 6 per cent—did our Prime Minister get a promise from the American authorities on his recent visit that they would reduce their re-discount rate from 4 per cent to 31 per cent so that we could soon effect this move? --but the Treasury has no hope of bringing down the long-term rate of interest by 1 per cent or more unless it gets the market—and that means the life funds—to co-operate in a sustained buy- ing movement. Now I venture to make this sug- gestion, which I hope Mr. Callaghan will con- sider. Let him say to the life companies that he will remove them from the capital gains tax on their gilt-edged operations if they will undertake to put at least 25 per cent of their new money into government funds. I am sure that they would accept this measure of government direction in return for the freedom to manipulate their gilt- edged portfolios free of capital gains tax. In the share markets they would still pay capital gains tax, but their exemption from capital gains tax in gilt-edged would enable them to become agents of the Government in the furtherance of cheaper borrowing and cheaper housing. On the conclu- sion of such a deal they would probably put the whole of their new money into government bonds until the market had had the. rise which the nation needs.

On the second count, the trouble arises because of the incidence of the new tax proposals on the companies operating overseas. This particu- larly applies to the British' oil companies. The Chancellor recognised their difficulties because the extra amounts required to 'gross up' their present tax-free dividends would be so huge— £29.4 million in the case of Shell and £22.4 million in the case of British Petroleum. He has therefore conceded that over the next five years they can apply the `overspill'—the excess by which the taxes paid overseas exceed the UK corporation tax due—to the relief of tax paid on' their share- holders' dividends. But this does not work out harmoniously. The Shell 'overspill' is only £9.3 million against the extra dividend cost of £29.4 million, and if it fried to maintain its share- holders' income, every extra 20s.' paid might in- volve 30s. to Royal Dutch shareholders under the 60/40 partnership agreement. It would prob- ably pay Shell to liquidate or sell out to Dutch and American interests. I am certain that the Chancellor never intended to force such an out- standingly efficient and progressive company as Shell out of the British household.

British Petroleum is our company : it is already 51 per cent owned by the British government. According to its annual statement, it contributed last year at least £67 million to the UK balance Of payments. It is the largest producer of crude oil in the Middle East, it refines oil in twenty countries, it owns a fleet of 125 tankers and charters nearly as many. Its net income on each gallon of oil sold was only three farthings. To stay in the highly competitive international oil business it has to spend vast sums each year on extending: and improving its facilities. Last year its capital expenditure was £169.1 million. It has to finance this expenditure out of retained earnings and from what it can borrow from the `risk investor.'How on earth can it go on financing itself on this huge scale if for every 20s. it earns it has to pay 12s. in tax overseas and then deduct 411 per cent out of any part of the remaining 8s. which it distributes to its shareholders as dividends? A !risk investor' paying 8s. 3d. in- come tax would only get 4s. 8d. out of every 20s. earned by the company and an investor paying the highest rate of surtax would only get 8d. No investor except a philanthropist would invest 'risk' money on such terms. Yet BP, like all other international oil companies, depends on `risk' capital being subscribed by the public. The idea that a transitional period of five years for the 'overspill' concession allows the company to grow sufficiently to offset the extra taxation with extra earnings is ludicrous, for no company can grow which finds itself starved of 'risk' capital. It seems obvious that the Chancellor's otherwise excellent tax reforms will gradually kill a UK- based oil industry. They may also drive overseas the great international mining groups—Rio Tinto- Zinc, Consolidated Goldfields, Selection Trust. Charter Consolidated, etc. which are at present registered in the UK. Surely this is not what Mr. Callaghan intended?

Of course, it was right to discourage portfolio investment overseas and to restrain the indis- criminate 'direct' investment overseas which has been putting our international account so much in the red, butt suspect that the Chancellor's academic advisers have no clear idea as to how much direct investment in overseas subsidiaries by our leading manufacturers helps our balance of payments through higher exports. `The whole point of our foreign investment programme,' said the managing director of Leylands, 'is to en- courage exports. That's why we do it.' He claims to get back 70s. in exports for every 20s. invested overseas. It would be a blow if the new taxes upset British participation in joint ventures with local industrialists-especially in developing countries with high tariffs. Clearly the Finance Bill in certain particulars needs a careful re- think.

Previous page

Previous page