Middle East

Israel and her risks for peace'

Patrick Cosgrave

On the surface at least it is bewildering to observe the contrast in Israel between a totally united and totally dedicated nation, and the profusion of Israeli political parties. The country as a whole is a curious combination of the relaxed and intense. I observed this to Mr An Rath, editor of the Jerusalem Post, who grinned and said, "You have come, you know, to the orient, and here we are very fatalist." Nonetheless, it bespeaks a massive inner confidence that the Israelis are able — convinced though many of them are that Egypt will abide by no disengagement agreement, and that they have been or are about to be betrayed by Dr Kissinger, for whom there is a growing loathing and about whom many scabrous jokes circulate — to carry on a pleasant, hospitable and outgoing national life. It is also an almost fanatically constructive one.

I was able, at the end of last week, to pick delicious apples in an Israeli orchard virtually on the front line at the Golan Heights, for the Israelis will allow no opportunity to sow and reap to be missed, and in this area at least the local kibbutzniks are anxious to point out to the visitor that the land, the possession or at least occupation of which the Syrians dispute with them, had, under Arab administration, been laid waste. A companion on the heights pointed towards the ghost city of Kuneitra, in Syrian territory. "Where the orchard ends," he said, "Israel stops."

For all its essential unity, however, Israeli society is deeply divided over the attitude which ought to be taken towards the Kissinger-Sadat formula for disengagement in Sinai. (It should be stressed, by the way, that only a further disengagement is at issue: neither peace, nor even non-belligerence, on any terms, are on offer from the Arabs.) I expected to find that at least some of the Israelis I would meet would be, in the cant phrase, hawks — that is, people itching to have another go at the Egyptians, and put beyond doubt the verdict every military historian will record on the Yom Kippur war, that it was a smashing Israeli victory, more considerable even than that of 1967, the fruits of which were snatched from the conquering Israeli defence forces at the very last moment by the United States. However, though it is true that Israelis of all shades of opinion seem convinced that only the lack of nerve of their own government and the perfidy of the Americans denied them the extra thirty-six hours they needed to crush the Egyptians and the Syrians beyond doubt, and utterly to destroy the Egyptian Third Army, I found no senior Israeli politician or soldier, of whatever shade of political opinion, who was not heartily sick of war, and desperately anxious for a peace. What is at issue is the character and number of the risks Israel should take for peace — 'risks for peace' is' a phrase that recurs in almost every conversation.

That is not to say that the Israelis do not continue to have considerable contempt for the fighting qualities of the Arab armies, and even more for the deceits of Arab governments. When President Sadat recently observed that only super-power intervention prevented the Arabs from dictating terms at the end of the 1973 war, Israeli opinion was expressed in a Post cartoon which pretended to accept the Egyptian President's thesis, but ended with a panel observing that the Third Army had had the Israelis surrounded, 'from the inside.' Another senior journalist, a deeply and bitterly depressed man, who was a fund of anti-Kissinger jokes, said in an almost offhand way, "Of course we can lick them again, and again, and again if need be. But think of the cost."

The question of cost has everything to do with attitudes to the suggested dispositions of forces in the Sinai. There are three broad reasons for agreeing to a withdrawal from the passes in accordance with American and Egyptian wishes. First, the subsequent attitude of Egypt will indicate whether she is willing to go further, over however long a period, towards a genuine peace. Since the Israelis are acutely aware of massive and growing internal Egyptian problems, and since they realise that Libya poses a threat to Egypt on the other side, there is some disposition, especially in government circles, to take a chance. Second, there is some inclination, especially among civilian civil servants who accept the fact that the Israeli Army has never been in better shape, to believe that, even if they are compelled to retreat from the passes, the IDE would be able to repeat a sixday war type campaign against Egyptian forces debouching from the passes. Thirdly, the Israelis are anxious to please the Americans, not only in terms of politics, but in terms of diplomatic strategy. There is considerable talk in Israel of Portugal, and a fear that, if the Communists win in that country and the Americans are not enabled to keep their grip in Egypt, the Mediterranean will become a Soviet lake, with Italy and Greece scheduled also to fall into the Russian thrall.

Objectors to the agreement concentrate in the first instance on the position of the Israeli Army after a withdrawal. They do not believe in the genuineness of Egyptian intentions, and they fear the terrible burden the youngsters of the IDE will have to carry. (When Israelis speak of our boys' in the Army they do so in no sentimental spirit: the armed forces, and the legions of young women on whom their administrative structure depends, are staggeringly youthful.) "You must remember,said one man to whom I spoke, "that nothing like the 1967 war can ever happen again. For one thing there has been a complete change in world strategic conditions. Nowadays the scale of even a local war is so great that it cannot be sustained without the kind of material pro vision that only a super-power can make. Even if the entire European arms industry offered its total output to the Israelis or the Arabs we would not have enough stuff to keep a war going for more than a week or so. And the defences which the Egyptians are now creating, with Russian help, are so strong that the could probably be taken only at great cost.' And a young soldier with whom I talked gave me an army view with the aid of a map. "If we have to pull back," he said, "it will mean that we must deploy much larger defensive forces on the plains on our side of the passes. We must do that to be secure, for if the Egyptians were to pierce a line beyond the passes they would be at the heart of Israel, and every Israeli soldier has it drummed into him that, while a battle lost by the Arabs means to them only the loss of an army, to us it means the loss of our country." So, in order to ensure their security the Israelis would have to deploy larger forces, partly because the terrain, is more favourable to an attacking force beyond the passes, partly because, even with Americans in charge of early warning devices within the passes, Israeli devices further back would have hills between them and the enemy, and would be much less efficient at monitoring his movements. "All this," my soldier friend went on, "means large,f forces, more frequent calls to the reserves, and an even greater load on the Israeli econonlY' We will have to redistribute the burden on the girl soldiers as well as the men." He grinned, and added, "If you come back in six months a girl will be doing my job." The same point was made by all the spokesmen of the Likud, the coalition of opposition parties (to which General Ariel . Sharon, the victor of the crossing of the Canal in 1973, and now principal military adviser t°, Prime Minister Rabin, belongs). Mr Shan° Tamir, one of their most able spokesmen, preferred to emphasise doubts about Egyptian intentions. With that vividness of phrase which all Israelis, even if their first language is not English, seem to possess, he waved his arms and exclaimed, "How can you rely on the professions of a power which professes daY after day that your country is an excrescence which must be vomited from the area? Our government is allowing the Americans t° impose on us a risk which may end in out destruction." And yet, military though she is, 'Israel remains a completely free society: when I took a dispatch for London to the military censor he glanced through it only briefly, searching onlY for what might be an impermissible reference to military dispositions. And when 1 asked an army spokesman about the balance between regulars and reservists in the IDE he shook his head and said, "We never give numbers." F01 the rest, no attempt is made to jam the bloodthirsty broadcasts of the Arab rach° stations, even when they strive to incite the Arab population in Israel; and Arab newspapers are wholly free to repeat that propaganda within the borders of Israel itself. I listened t° several accounts of meetings of the Prirne Minister's editors' committee, which discusses regularly the news of the day and, after liearin reservations exPressed about whether or not inhibited critical news coverage, I could stn,l not accept that it differed in any material degree from the lobby system in Britain. Nor' for that matter, is there activity by the securitY forces comparable to that of the British AMY JO Northern Ireland. Every possible effort, even al considerable risk, is made by the government to preserve the even flow of the quotidian activities of a wholly free society. True, I was a little chilled when my dri■ stopped to fill his tank at the outset of a trip 1° the Negev and Dimona, where the Israeli nuclear reactor is sited and, on returning to the wheel, tossed a Biretta on the seat beside hirn„' But apart from taking the safety catch 0" during the long desert run down to Beersheba' no action was called for from him. (One of the reasons for this sense of a security which'

though armed, is not inhibiting, was given to me by a senior Arab politician in Nazareth. I had expressed polite scepticism about his Professions of loyalty to the state of Israel, and he insisted that my instincts were wrong. "I have lived here for twenty-eight years," he said, and my people, though there are too many of them for this city, now have all the necessary services available. The Israelis have governed here well and where once the people would not pay taxes they now come voluntarily and pay them. Besides" and here he spread his hands and grinned "if the Arabs came here tomorrow I would be dead, and many friends With me.") There is one concrete example of Israeli attempts to extend their conception of freedom towards their neighbours. There is total freedom for any Arab citizen to travel to and about Israel. (I should mention, though, that Israelis expect their guests to work: after the six-day war a group of captured and highranking Egyptian officers were given a highPowered, gruelling, VIP tour of Israel; and they complained to the Red Cross about maltreatment.) This freedom is given particular expression at the Allenby Bridge, between Israel and Jordan, where Arabs arrive every day, to cross into enemy territory and visit relations or old homes. Security is, of course, strict, and before entering Israeli territory the visitor must endure a long, frustrating and thirsty wait in the dust and the heat while everybody is thoroughly searched. A problem, too, arises in that the Jordanians habitually send over, in a day, more buses than have been agreed with the Israelis, and more people than the security forces can comfortably handle, so it sometimes happens that disappointed visitors have to be returned to Jordan at the end of the day, to begin the whole wretched ,business all over again on the morrow. Still, they come every day in their hundreds and even thousands 1,800 had already been cleared for entry by the afternoon of the day on which I visited the bridge. And the Israelis have tried to create the same 'open bridges' agreement with Egypt, but have been turned down.

It is this sort of attitude on the part of the Egyptians which gives rise to Israeli suspicions of President Sadat's intentions. Mr Tamir, and his colleague Dr Rimental, insisted, convincingly to my mind, that despite the hawkish

reputation of Likud abroad, they do want a genuine peace. Mr Tamir, in particular, reminded me of his own suggestion that Israel Should offer an open frontier to the Lebanon, in return for which realising that the Lebanese, like the Egyptians, would meet with hostility from the more extreme Arab governments ifSuch a suggestion were entertained Israel Would accept and settle all the Arab refugees Presently plaguing the Lebanese government. He also reminded me that he, who has frequently been accused of racism, has fought many Arab civil rights cases in his capacity as' an advocate.

In principle, of course, much of the Middle Eastern dispute is about territory rather than People. There is a certain lack of imagination on the part of the Israelis in their inability to comprehend that the fact that they cultivate every possible square inch of land, whereas the Arabs fecklessly neglected the riches of the soil, does not count much in the outside world's judgement of who actually owns, or should °Nwn, the land. In the West Bank, as near the Golan, they have planted settlements of their oWn in occupied territory, both to increase their agricultural output and because these „settlements of armed farmers not always in -`kibbutzim increase security potential. But the government takes great care to ensure that settlements are made only with its own express Permission, and no security of tenure is offered the settlers. True, a certain strain of expansionary Zionism remains in many considerations of the West Bank, for there are in that territory many places sacred to any religious or historical conception of Judaism.

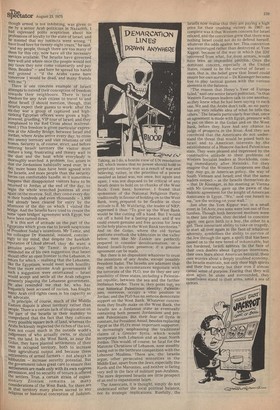

Zr4N-"TC-A-7 Taking, as I do, a hostile view of UN resolution 242, which insists that no power should hold in perpetuity territory won as a result of war and believing, rather, in the priorities of a power assailed as Israel was, not once, but again and again, I was not disposed to be critical of any Israeli desire to hold on to chunks of the West Bank. Even here, however, I found that spokesmen of the National , Religious Party, traditionally in favour of holding on to the West Bank, were, prepared to be flexible in their attitude to it. Mr Wahfartig, the leader of NRP, expressed it thus: "To give up the West Bank would be like cutting off a hand. But I would cut off a hand for a lasting peace, and if we could ensure genuine and free access for Jews to the holy places in the West Bank territories." And on the Golan, where the old Syrian positions overlook the kibbutzim in the valley below, men like Mr Zankin are perfectly prepared to consider demilitarisation, or a shared Israeli-Syrian presence, if a genuine agreement can be made.

But there is no disposition whatever to trust , the intentions of any Arabs, except possibly President Sadat. The Israelis are adamant that they will in no circumstances negotiate with the terrorists of the PLO, nor do they see any possibility of three states, including a Palestinian republic, between the sea and the farther Jordanian border. There is, they point out no true historical Palestinian identity; Palestinians, moreover, occupy a vital position in Jordan; and the PLO has no serious democratic support on the West Bank. Whatever concessions they finally make on the West Bank, the Israelis see a Jordanian state as eventually containing both present Jordanians and present Palestinians. But their fear of Syria is constant, for President Assad, besides replacing Egypt as the PLO's most important supporter, is increasingly emphasising the traditional claims of a Greater Syria, which would incorporate both Lebanon and at least North Jordan. This would, of course, be fatal for the Maronite Christians of Lebanon, now steadily losing out in the birthrate competition with the Lebanese Muslims. There are, the Israelis argue, other persecuted minorities in the Middle East, apart from the Jews,,especially the Kurds and the Maronites, arid neither is faring very well in the face of militant pan-Arabism. The more depressed Israelis see little prospect of an end to expansionist Islam.

The Americans, it is thought, simply do not understand either the local political balance, nor its strategic implications. Ruefully, the

Israelis now realise that they are paying a high price for their crushing victory in 1967: so complete was it that Western concern for Israel relaxed, and the conviction grew that there was nothing Israel could not do to defend herself, whatever the odds against her. This conviction was encouraged rather than destroyed at Yom Kippur, because of the way in which the IDE recovered from what, for most armies, would have been an impossible position. Once the , dominant concern, especially in the United States, ceased to be the survival of Israel once, that is, the belief grew that Israel could ensure her own survival Dr Kissinger became free to play tactical games with the various elements in the balance.

"The reason that Henry's Year of Europe failed," said one senior Israeli politician, "is that Western European leaders talk to one another, sorhey knew what he had been saying to each one. We and the Arabs don't talk, so no party has any very reliable idea of what he tells the others." The Israelis particularly fear that, once an agreement is made with Egypt, pressure will be put on them in the Golan and on the West Bank, before they have had any chance to judge of prospects in the Sinai, And they are convinced that the Americans do not understand the threat that would be posed both to Israel and to American interests by the establishment of a Moscow-backed Palestinian state. They were pleased and impressed by the constructive attitude to their problems of Western Socialist leaders at Stockholm, coming immediately after Helsinki, for they imagine-that the Western Europeans see that they may go, in American policy, the way ofSouth Vietnam and Israel; and that the same leaders suspect as the Israelis themselves do that Dr Kissinger, in his meeting at Vienna with Mr Grornyko, gave up the pawn of the Helsinki agreement for the knight of American dominance in Egypt. "We," said one Israeli to me, "are the writing on your wall."

Just after the Yom Kippur war, in a small street in Tel Aviv, two sons were lost out of five families. Though both bereaved mothers were in their late thirties, they decided to conceive again: one gave birth to a boy, the other to a girl. Their insouciant ability to take on tragedy, to start all over again in the face of whatever adversity, symbolises the ability to survive of the Jew through the ages, a spirit that has been passed on to the new breed of indomitable, but not hardened, Israeli sabbras. In the face of their own doubts about Egyptian intentions, their own fears about American betrayal, their own worries about a deeply troubled economy, the Israelis maintain, not only their high spirits and their free society but their iron if almost casual sense of purpose. Fearing that they will soon again be alone and surrounded, they nonetheless stand to their arms, amid a sea of terrors.

Previous page

Previous page