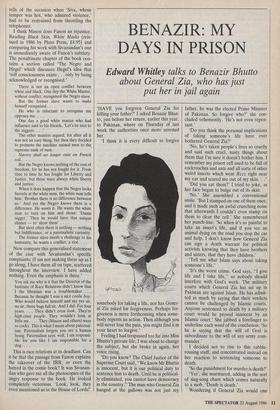

BENAZIR: MY DAYS IN PRISON

Edward Whitley talks to Benazir Bhutto about General Zia, who has just put her in jail again

`HAVE you forgiven General Zia for killing your father?' I asked Benazir Bhut- to, just before her return, earlier this year, to Pakistan, where on Thursday of last week the authorities once more arrested her.

`I think it is every difficult to forgive somebody for taking a life, nor has Gener- al Zia asked for forgiveness. Perhaps for- giveness is more forthcoming when some- body repents an action. Then although you will never lose the pain, you might find it in your heart to forgive.'

Feeling I had trespassed too far into Miss Bhutto's private life, I was about to change the subject, but she broke in again, her voice rising.

`Do you know? The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court said, "We know Mr Bhutto is innocent, but it is our political duty to sentence him to death. Until he is political- ly eliminated, you cannot have democracy in the country." The man who General Zia hanged at the gallows was not just my father, he was the elected Prime Minister of Pakistan. So forgive who?' she con- cluded vehemently. 'He's not even repen- tant.'

`Do you think the personal implications of taking someone's life have ever bothered General Zia?'

`No, he's taken people's lives so cruelly and said such cruel, nasty things about them that I'm sure it doesn't bother him. I remember my prison cell used to be full of cockroaches and ants and all sorts of other weird insects which went Bzzz right near my ear and scared me out of my skin. .

Did you eat them?' I tried to joke, as her face began to bulge out of its skin.

`No.' She assembled a conventional smile. 'But I stamped on one of them once, and it made such an awful crunching noise that afterwards I couldn't even stamp on them to clear the cell.' She remembered her punch-line: `So when it's so painful to take an insect's life, and if you see an animal dying on the road you stop the car and help, I don't know how General Zia can sign a death warrant for political activists knowing that they have brothers and sisters, that they have children.'

`Tell me what Islam says about taking someone's life:' `It's the worst crime. God says, "I give life and I take life," so nobody should interfere with God's work. The military courts which General Zia has set up in Pakistan are against Islam. He has admit- ted as much by saying that their verdicts cannot be challenged by Islamic courts. Anyone sentenced to death by a military court would be proved innocent by an Islamic court.' She jabbed a forefinger to underline each word of the conclusion: `So he is saying that the will of God is subordinate to the will of any army com- mander.'

I decided not to rise to this rabble- rousing stuff, and concentrated instead on her reaction to sentencing someone to death.

`So the punishment for murder is death?'

`Yes', she murmured, adding in the sort of sing-song chant which comes naturally to a mob, 'Death is death.'

Wondering if General Zia would one day hear this, I asked, `Do you reconcile yourself to that?'

`With death? With taking someone's life?'

`Yes.'

Miss Bhutto recognised a direct question when she saw one, and shied well away.

`Challenging is not a subject that I have devoted much time to. I know my father's first act when he became Prime Minister was to commute all the pending death sentences — and his last act. When we were waiting at home for the Army to come after the coup d'etat, he picked up this huge pile of black folders (death warrants always came in black folders and he hated them) and just commuted them. He was so magnanimous. . . ."

`No,' I interrupted. '1 wanted to know what you would feel about sentencing someone to death.'

Miss Bhutto reluctantly reconsidered the question. 'What do I feel about sentencing Zia to death for murdering my father, or just general death sentences?'

`Zia.'

`That will depend upon the parliament of the country. Obviously he has committed a judicial murder, but he will be judged both by the people, and by his own attitude. Whether he repents or not.'

`Do you agree with death sentences?'

`Islam says you can take an eye for an eye, but it also stresses compensation. In general terms, I don't think death sent- ences are a good thing because innocent people like my father or our followers can die, and once a life is gone you can never bring it back. But I also feel that in the West the law has gone too far and too many guilty people get off because "reasonable doubt" has become so elastic. The case of my younger brother, who my entire family is convinced was killed by his wife, has given me an eye-opener into Western justice. They say that even if you are 99 per cent convinced, they won't bring a charge because the jury will let it off on that one per cent. I mean 99 per cent! How can they do things like that?'

Having lived very much in the context of death, Miss Bhutto is well placed to quan- tify it in percentage terms. Her father was hanged in 1979, her brother died last year. Since General Zia's coup in 1977, she herself has spent her life either in prison or exile, including a year in solitary confine- ment. I wondered how she had got through it all.

`It was pretty much a nightmare.' She tucked her feet up beneath her on the sofa and hugged her knees to her chest. 'I remember those years from 1977, with my father in prison and none of us knowing what might happen to him. Then his assassination in 1979 and my imprisonment not knowing if I would be sentenced to death. Because I was in solitary confine- ment, I could never talk to anyone about what would happen, so I used to just gear myself to passing each day.' `How did you pass it?'

`Well, there's not much you can do in a cell. I used to pray a lot and do little exercises. I was conscious that I must get up at a fixed time. They take away your watch, but there is a jail clock which chimes on the hour. By that chime I timed myself and would walk back and forth for an hour. It's not an exciting routine, but you have to do things according to time otherwise you get lazy. It gets difficult because you don't want to get up, you don't want to throw water on your face, a lassitude grips you. You have to constantly fight against that lassitude so when you reach the end of the day you can say, "Well, whatever the future holds, it's one day closer." ' `So you had no idea what was going on outside?'

`No idea at all.'

`You didn't talk to your guards?'

`I used to try when they brought my food, but they would give me scared looks and scuttle away as fast as they could - which was hardly comforting! Bureaucrats, especially petty bureaucrats, are the most scared people around. If they think your life is threatened, they won't touch you with a bargepole, but if they think you're going to be okay, they fawn around you.

When I was released, one of the guards came up to me and said, "You know my son, could you get him a job in a fac- tory?" ' Miss Bhutto laughed for the first time, an uneasy rattle of nerve-ends.

`What was it like when you were re- leased?'

She stopped laughing. 'I was paranoid.

remember continuously feeling breathless and looking over my shoulder the whole time. I didn't want to go out of my flat because I found the world threatening. I hadn't dealt with human beings, so I had no topics of conversation. I had not read a single thing for three years — even Time and Newsweek were considered communist literature and not permitted.' She smiled. `I'm sure that will interest them.'

`And without your father, who is your support in life, who is your anchor?'

`I don't have any anchor in life now. It is terrible. It's the worst thing in life. I mean, I could tell you that the people of my country who share my vision of Pakistan are my anchor, but that's too abstract. To have one person behind you, to know that whenever you are in trouble, no matter what, you can fall back on him — I don't have that.'

`What about marriage? That would give you an anchor.'

Miss Bhutto's face distorted into anger like one of those grotesque circus mirrors.

`It would have been shocking if I had got married when my father was fighting for his life in jail. I could not even go out and see a movie, because people would laugh at me and say, "Her father's in a death cell and she's running around enjoying herself! She expects us to come out and risk going to prison for her cause when she's having a good time!" Oh no! It involves sacrifice, putting aside life's normal pursuits. I would not have been able to live with myself if I had been thinking of romantic pursuits.'

`What about now though?' I persisted.

`Now my brother's dead. He's just been killed last July [1985], and we mourn for one year when a member of our family dies. For the death of my father we mourned two years. So, you see, when there is a death in the family these things are considered distasteful even to talk about.'

was just trying to make the point that marriage would give you an anchor in life, something you haven't had since your father's death.'

`I don't think marriage is such an anchor. Unfortunately I did not keep it, but in the Herald Tribune a few days ago I read an article which said how other people love you for what you are achieving; but your family accepts you just for what you are, for better or for worse, because you are the same blood. A father accepts you because you are his daughter, but a husband/wife relationship is not like that. I know the marriage vow is "for better or for worse", but I think your husband prefers to accept you "for better". He has fallen in love with an image of a person, with the person he hopes you will be. He might be disillu- sioned if you fail. But your parents, they accept you from the time you are having your first bottle of milk right through to when you are 16 and having Coca-Cola and leaving empty cans around the place!'

`Don't you yearn for that sort of security?'

Miss Bhutto fidgeted with a bracelet for a moment. I wondered if her father had given it to her. 'I don't think. . . I don't know. You see, my life has always been one of self-denial. To lose your liberty is one of the worst things, because you feel like you're in a grave. You're watching life pass by, and the days leave you older and older, and you're doing nothing. I couldn't have survived my imprisonment unless I had realised how much I was prepared to pay. I asked myself: "Do I really want a democratic Pakistan? Do I want to carry out my father's ideals? And if so, what price am I prepared to pay? Because if you are not prepared to pay the price, you have no business being in this political life." So it has been a life of self-denial, it has been one of knowing my best years have gone bad.'

Miss Bhutto showed me down the stairs, telling me she would be off back to Pakistan next month to continue her quest for democracy. So far she has found a prison.

Edward Whitley's first book, The Gradu- ates, was published in April (Hamish Hamilton, £12.95).

Previous page

Previous page