Paying the penance for Culture

Lloyd Evans, on his first visit to Edinburgh, finds a grey city in need of a Parliament

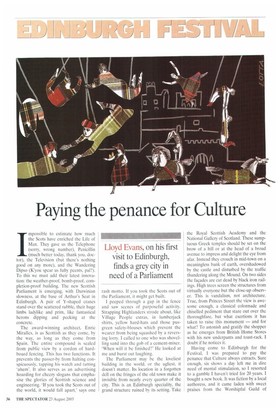

Impossible to estimate how much the Scots have enriched the Life of Man. They gave us the Telephone (sorry, wrong number). Penicillin (much better today, thank you. doctor), the Television (but there's nothing good on any more), and the Wandering Dipso (K'you spear us fufty peents, pal?). To this we must add their latest innovation: the weather-proof, bomb-proof, completion-proof building. The new Scottish Parliament is emerging, with Darwinian slowness, at the base of Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh. A pair of Y-shaped cranes stand over the scattered nibble, their huge limbs ladylike and prim, like fantastical herons dipping and pecking at the concrete.

The award-winning architect, Enric Miralles, is as Scottish as they come, by the way, as long as they come from Spain. The entire compound is sealed from public view by a cordon of hardboard fencing. This has two functions. It prevents the passer-by from halting conspicuously, tapping his watch and tutting 'ahem'. It also serves as an advertising hoarding for cheery slogans that emphasise the glories of Scottish science and engineering. 'If you took the Scots out of the world, it would fall apart,' says one rash motto. If you took the Scots out of the Parliament, it might get built.

I peeped through a gap in the fence and saw scenes of purposeful activity. Strapping Highlanders strode about, like Village People extras, in lumberjack shirts, yellow hard-hats and those pusgreen safety-blouses which prevent the wearer from being squashed by a reversing lorry. I called to one who was shovelling sand into the gob of a cement-mixer. 'When will it be finished?' He looked at me and burst out laughing.

The Parliament may be the loveliest building in the world, or the ugliest, it doesn't matter. Its location in a forgotten dell on the fringes of the old town make it invisible from nearly every quarter of the city. This is an Edinburgh speciality, the grand structure ruined by its setting. Take

the Royal Scottish Academy and the National Gallery of Scotland. These sumptuous Greek temples should be set on the brow of a hill or at the head of a broad avenue to impress and delight the eye from afar. Instead they crouch in mid-town on a meaningless bank of earth, overshadowed by the castle and disturbed by the traffic thundering along the Mound. On two sides the facades are cut dead by black iron railings. High trees screen the structures from virtually everyone but the close-up observer. This is vandalism, not architecture. True, from Princes Street the view is awesome enough, a classical colonnade and chiselled pediment that stare out over the thoroughfare, but what exertions it has taken to raise this monument — and for what? To astonish and gratify the shopper as he emerges from British Home Stores with his new underpants and toast-rack. I doubt if he notices it.

Having come to Edinburgh for the Festival, I was prepared to pay the penance that Culture always extracts. Sure enough, six shows a day left me in dire need of mental stimulation, so I resorted to a gamble I haven't tried for 20 years. I bought a new book. It was fiction by a local authoress, and it came laden with sweet praises from the Worshipful Guild of Female Writers (Hampstead Branch): Natasha Walter, Rachel Cusk. Fay Weldon and Germaine. It was garbage. I threw it away on p.26 and went into Save the Children, where I sifted the tatty shelves and bought Herbert Read's The Meaning of Art for a few pennies. Inestimably better. If every publishing house were this very minute to cease its work for ever, how long before the world ran out of good reading? Thousands of years.

I've never visited 'the Athens of the North' before and what a grey city I found it. Endless boulevards of scarred granite flaking under a crust of satanic filth. Witchy gables everywhere and joyless lines of cramped, mean little windows. From certain angles Edinburgh looks like no capital in Europe so much as East Berlin. And, God, it could do with a scrub. Architecturally, its finest moment is the Royal Mile viewed from Princes Street. Up this gentle gradient marches a pageant of stately monuments in intermingled styles, the stern Gothic, the temperate Classical and the flashy Tyrolean, whose diversity somehow harmonises with the wild and stormy slopes of the hill. The Castle makes a dramatic climax with its shining walled turrets and Colditz roofs and that terrible plunging precipice of sheer green lawns and dragony outcrops of rock. Hard to look at without feeling your palms grease up.

Everything else is grey, grey, grey. And white, too. I missed the exotic tints of London's Eastern faces. The entire population is blue-eyed, pale and freckled, apart from the Asians, of course, who run the mini-markets and newsagents, as they do in every city I can think of. Where is it written in their holy book, '0 my tribe, sorrowing exiles shall you be, wandering the earth and purveying tobacco'?

In the evenings, at a cornershop on Candlemaker Row, I purchased the simple pasty-and-a-Fanta supper which sustains the arts correspondents of frugal magazines like this one. At the till was a voluptuous teak-skinned beauty whom I bantered with compulsively. She almost defied belief: the face of Cleopatra and the voice of Bill Shankly.

After a week of sensory deprivation, sorry, cultural joy, I was glad when my train (GNER, punctual) finally purred into King's Cross. I clambered on to the platform and headed for the Tube, feinting and dummying my way through the crowds. Near the ticket-office, lingering in an archway. I saw an ancient crooked goblin, leaning against the stonework as if he were part of a cathedral grotesque. He flipped himself forwards and limped towards me — scuffed grey hair, a honeyed tan, flaring red cheeks and blue eyes blazing — and he addressed me in that harsh, luxurious Lowlands burr. `K'you spear us fufty peents, pal?' Home at last.

Previous page

Previous page