FIRST-CLASS FREE LOAD

Patrick Skene Calling is treated

to a gastronomic holiday that is just the ticket

IN every metropolis, I suppose, there are tycoons whose style may be cramped tem- porarily by an impediment in the cash flow, between one big deal and another. My friend Vincent, having painfully stubbed his toe in the City, has recently been resting longer than usual while considering what to get into next.

'During the present hiatus,' he said on the telephone the other morning, 'it is important to maintain one's morale, keep the wits well honed, and so on. Are you doing anything for lunch?'

As it happened, I was not busy. In memory of his lavish hospitality in the past, I was glad to be able to treat him to a meal.

'The Connaught?' I suggested, not with- out a certain apprehensiveness, for I have never been as rich as he sometimes is.

'No, no, no!' he protested genially. 'I'm not asking you to ask me to lunch. This expedition was my idea. All I want from you is your company. Almost all.'

'But surely it's my turn,' I murmured.

'No. This little outing is something I thought up just today in the bath. It'll do both of us a lot of good. It may well change the pattern of social life as we know it. In addition to your presence, actually there is one contribution I need from you.'

Oh, I thought. Here it comes.

'Are you still there?' he asked.

'Yes,' I admitted.

'You have to bring some cash.'

'Yes,' I said with a sigh. 'How much?' 'Enough for two tickets from London to Paris.'

'Paris!' That must mean the Tour d'Ar- gent or the Grand Velour or at least the Crillon. Wasn't that rather extravagant, even for someone whose morale needed a boost?

'Paris,' he confirmed. 'First class.'

'London-Paris first-class return must be —' I could only hazard a guess. I fly to Paris only infrequently, and then always executive class or even economy.

'First class,' he repeated emphatically. 'But not return. I've checked on the one-way fare.' This was in the peak season. 'It's £167 — £334 for the two of us.' Some lunch! And that was what it would cost the guest.

But Vincent —'

'Why only one way?' he said, as if reading my mind. Even over the tele- phone. I could detect his characteristically cryptic smile. He enjoys mystifying others. 'That's all you have to bring,' he assured me. 'In cash, please. You'll see soon enough how it's all going to work out. You'll get your money back.'

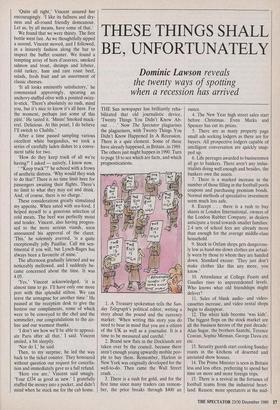

How and when? I wondered, not very optimistically. I trust him but there are times when he seems maiiana-orientated. Was he counting on funds from some French business associate? As far as I knew, he had dealings with only a charm- ing but languid marquis, whose principal function was to add Continental éclat to Vincent's letterhead. Having pocketed my passport and vi- sited my bank, I took a taxi to Vincent's mews house in Belgravia. He was already outside the yellow door, dressed in a cheerful tweed suit, a soft brown hat and brown suede shoes, as if going to an informal race meeting. He was wearing. a red carnation in his button-hole and a grin on his roundish, pink face, so I realised he was in a playful mood. I wished I were too. Slamming the taxi door behind him, he told the driver to take us to Heathrow.

`Which terminal, guy?'

Vincent said he wanted the one from which planes left for Paris, and told him the name of the airline.

`Why that one?' I asked. I wasn't object- ing; I was merely curious. It was a long- established, reputable national airline, but not the one that would first have sprung to mind.

'Their new advertising campaign is in- comparably superior to the others',' Vin- cent replied. 'They are really trying to please. Haven't you noticed? They obviously understand about food and drink. They sympathise with gluttons. Their stewardesses are the prettiest.'

At the airport, I gave Vincent the money. He went to get the tickets, while I looked at magazines.

'What's our flight?' I asked. I like to be on time. He smiled complacently.

'The 4.50,' he said.

'4.50! I thought we were going to have lunch.'

'We are. Oh, we are!'

He led the way to the newly redecorated first-class departure lounge, whose luxu- rious facilities are open, of course, only to bearers of first-class tickets. Vincent uttered a conventional pleasantry or two as he showed our tickets, and the beautiful hostess beamed as warmly as a breakfast- show presenter. The lounge was gently animated by the small talk of elegant men and women. The place was not crowded. Everything about it was pleasantly soft: the lighting was soft; the music was soft; softly upholstered, dull-golden armchairs were disposed here and there in discreetly separated groups; the dark-saffron carpet was soft on the way to the long, richly- stocked bar and buffet.

`Champagne first, don't you agree?' Vincent suggested. 'I always say it's the best thing to rinse the taste-buds with, early in the day.' A softly illuminated golden clock on the wall indicated that the time was 11.40, five hours and ten minutes to our scheduled time of take-off. Cham- pagne, I thought, was a good idea.

'Have you any Bollinger?' Vincent en- quired of the young blonde barmaid, whose voluptuousness mocked the restric- tion of her well-cut uniform. 'Or Veuve Clicquot would do.' Thus began the first of many interesting discussions which en- livened the hours.

The champagne is Piper-Heidsieck,' the barmaid informed us. 'Is that all right?' `Quite all right,' Vincent assured her encouragingly. 'I like its fullness and dry- ness and all-round friendly demeanour. Let us, by all means, have some of that.'

We found that we were thirsty. The first bottle went fast. As we thoughtfully sipped a second, Vincent moved, and I followed, in a leisurely fashion along the bar to inspect the buffet counter. We found a tempting array of hors d'oeuvres, smoked salmon and trout, shrimps and lobster, cold turkey, ham and rare roast beef, salads, fresh fruit and an assortment of classic cheeses.

`It all looks eminently satisfactory,' he commented approvingly, spearing an anchovy-stuffed olive with a pointed swizz- le-stick. 'There's absolutely no rush, mind you, but it's nice to know it's all here. For the moment, perhaps just some of this pâté.' He tasted it. `Mmm! Smoked mack- erel. Delicious. At this point, I do believe I'll switch to Chablis.'

After a time passed sampling various excellent white burgundies, we took a series of carefully laden dishes to a conve- nient table for two.

`How do they keep track of all we're having?' I asked — naïvely, I know now. "Keep track"?' he echoed with a frown of aesthetic distress. 'Why would they wish to do that? There is no time limit here for passengers awaiting their flights. There's no limit to what they may eat and drink. And, of course, there is no charge.'

These considerations greatly stimulated my appetite. When sated with sea-food, I helped myself to a generous selection of cold meats. The beef was perfectly moist and tender. Vincent, also having progres- sed to the more serious viands, soon announced his approval of the claret. `This,' he solemnly averred, 'is a quite exceptionally jolly Pauillac. Call me sen- timental if you will, but Lynch-Bages has always been a favourite of mine.'

The afternoon gradually latened and we noticeably mellowed, and I suddenly be- came concerned about the time. It was 4.05.

`Yes,' Vincent acknowledged, 'it is almost time to go. I'll have only one more port with this splendid stilton. We can leave the armagnac for another time.' He paused at the reception desk to give the hostess our compliments, some of which were to be conveyed to the chef and the sommelier, our congratulations to the air- line and our warmest thanks.

`I don't see how we'll be able to appreci- ate Paris after all that,' I said. Vincent smiled, a bit sleepily.

`Nor do I,' he said.

Then, to my surprise, he led the way back to the ticket counter. They honoured without question our request for cancella- tion and immediately gave us a full refund.

`Here you are,' Vincent said smugly. `Your £334 as good as new.' I gratefully stuffed the money into a pocket, and didn't mind when he stuck me for the cab home.

Previous page

Previous page