LAMB AND SLAUGHTER

Paul Webb contrasts the humour

of Charles Lamb's writing with his tragic life

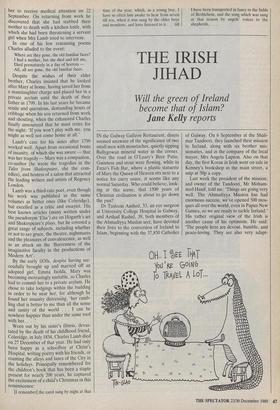

FEW of the .adults who buy Lamb's Tales from Shakespeare (first published 1807) as an educative but entertaining Christmas present for children are fully aware of the tragic relationship between Charles Lamb and Mary, his sister, co-author of the Tales, and murderer of their mother.

Charles Lamb was born on 10 February 1775, the third child of parents who work- ed (as factotum and housekeeper) for Samuel Salt, a one-time Member of Parlia- ment and director of the South Sea and East India Companies. His siblings were Mary (10) and John (12). The family lived in Salt's household in the Inner Temple, and Lamb was to be devoted to the buildings and traditions of the City of London all his life.

Following his brother to Christ's Hospit- al, a blue-coat school, he became a life- long friend of another pupil, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Slightly built, a vora- cious reader, crippled by a bad stammer, he could have been an easy victim for bullies, but his charm and good nature, which were to endear him to the most illustrious of his contemporaries, made him popular.

Leaving school at 14, he went to work for the South Sea Company, then moved to the East India Company, in whose service he remained until his retirement in 1825. Although he loathed the drudgery of the work he kept his sense of humour, describ- ing himself to a recently married friend as: married myself — to a severe step-wife, who keeps me, not at bed and board, but at desk and board, and is jealous of my morning aberrations. I cannot slip out to congratulate kinder unions. . . .

His humour was not to everyone's taste, especially his love of puns (which he shared with an admirer, the poet Thomas Hood), and he could be alarmingly eccentric at times. Describing himself in a mock auto- biography, Lamb alluded to these allega- tions, and characteristically used wit to defend himself:

Below the middle stature; cast of face slightly Jewish . . . stammers abominably, and is therefore more apt to discharge his occasion- al conversation in a quaint aphorism . . • than in set and edifying speeches; has conse- quently been libelled as a person always aiming at wit, which, as he told a dull fellow that charged him with it, is at least as good as aiming at dullness. . . .

Physically attractive, as William Hazlitt's painting of him in the National Portrait Gallery shows, he displayed little active interest in women other than in the out- pourings of adolescent verse. The reason for this was his devotion to his sister, of which De Quincey wrote 'The whole range of history scarcely presents a more affect- ing spectacle of perpetual sorrow . . . •' Mary, a spinster, looked after their aging and infirm parents, a responsibility that was too much for her, leading to a break- down in 1794. In 1796 her mental health was again giving cause for concern, and Charles unsuccessfully tried to arrange for her to receive medical attention on 22 September. On returning from work he discovered that she had stabbed their mother to death with a kitchen knife, with which she had been threatening a servant girl when Mrs Lamb tried to intervene.

In one of his few remaining poems Charles alluded to the event:

Where are they gone, the old familiar faces?

I had a mother, but she died and left me, Died prematurely in a day of horrors - All, all are gone, the old familiar faces.

Despite the wishes of their elder brother, Charles insisted that he looked after Mary at home, having saved her from a manslaughter charge and placed her in a private asylum until the death of their father in 1799. In his last years he became senile and querulous, demanding hours of cribbage when his son returned from work and shouting, when the exhausted Charles finally announced that he must retire for the night: 'If you won't play with me, you might as well not come home at all.'

Lamb's care for his sister after 1799 worked well. Apart from occasional bouts of insanity, of which she was aware — that was her tragedy — Mary was a companion, co-author (he wrote the tragedies in the Tales from Shakespeare, she the com- edies), and hostess of a salon that attracted the leading writers and artists of Regency London.

Lamb was a third-rate poet, even though his work was published in the same volumes as better ones (like Coleridge), but excelled as a critic and essayist. His best known articles (many written under the pseudonym 'Elia') are on Hogarth's art and Shakespeare's plays, but he covered a great range of subjects, including whether or not to say grace, the theatre, nightmares and the pleasures of convalescence, as well as an attack on the 'Barrenness of the imaginative faculty in the productions of Modern Art'.

By the early 1830s, despite having suc- cessfully brought up and married off an adopted girl, Emma Isolda, Mary was becoming increasingly unstable, so Charles had to commit her to a private asylum. He chose to take lodgings within the building in order to be near her, for although he found her insanity distressing, 'her ramb- ling chat is better to me than all the sense and sanity of the world . . . I can be nowhere happier than under the same roof with her. . .

Worn out by his sister's illness, devas- tated by the death of his childhood friend, Coleridge, in July 1834, Charles Lamb died on 27 December of that year. He had only been happy as a schoolboy at Christ's Hospital, writing poetry with his friends, or roaming the alleys and lanes of the City in the holidays. Principally remembered for the children's book that has been a staple present for nearly 200 years, he captured the excitement of a child's Christmas in this reminiscence:

[I remember] the carol sung by night at that

time of the year, which, as a young boy, I have so often lain awake to hear from seven till ten, when it was sung by the older boys and monitors, and have listened to it . . . till I have been transported in fancy to the fields of Bethlehem, and the song which was sung at that season by angels' voices to the shepherds. . . .

Previous page

Previous page