The neglected genius of Trieste

Anthony Blond

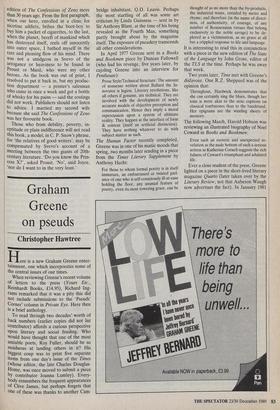

MEMOIR OF ITALO SVEVO by Livia V. Svevo Libris, £17.95, pp.178

You are an author who doesn't go' [Bookshop assistant to Svevo.] He abused the English and they applauded him' [Svevo on James Joyce.]

This memoir, slight and profound, pained yet tender and sweet-smelling like a rosa mundi, was written in the war by Svevo's widow while on the run from her native Trieste, which had a direct rail-link to Auschwitz. She never took that terrible train because the Italians successfully avoided delivery of their Jews to the Nazis, so she can be forgiven for not once referring to her husband's wholly — and her quarter — Jewish background.

Ettore Schmitz was one of eight surviv- ing children (another eight had died as infants) of a rich and cultivated Triestino Jewish family who, by virtue of the signifi- cance of that city, enjoyed better status than his co-religionists in the Austro- Hungarian Empire towards which his feel- ings, as in his choice of pseudonym — the Italian Swabian — were mixed. Livia Veneziani's father had invented a paint for the keels of ships which discouraged barna- cles. This was a good thing because Svevo was able to manage the company when his own father's business failed, a duty he performed as efficiently as his contempor- ary Kafka in the Prague insurance office. At Ettore's mother's deathbed — a scene banished by today's medicine — Livia, just out of the convent, offered Ettore a glass of marsala. He recognised that this was his life's companion. He was baptised, mar- ried her, and moved into the Villa Vene- ziani where he lived for 32 years. Every month he gave her his entire salary, keeping money only, one suspects, for the cigarettes which killed him. She chose his suits. He couldn't even undo a button.

There is little in this recollection of her husband — and it is the sweeter for it — to imply that Livia thought she was nursing a genius. Certainly he kept from her his `bitterness and disappointment' at the 'lack of recognition and understanding' he re- ceived until she read this in his journal during her long widowhood. In 1889 he

had offered a novel Svevo-esquely entitled Un Inetto (`The Inept One') to a Milan publisher who refused to publish a book with such a title. When finally he had to pay for the book to be printed, the reaction in the Italian world outside Trieste was nil, but he did get a letter from Munich recommending a 'happier and more signifi- cant subject-matter'. But Svevo would not change tack, and As A Man Grows Older, his next novel, was equally ignored, so that by 43 he felt his life was over and, as Livia put it, 'the writer in him asleep'.

However, the muses were stirring their stumps. In 1907 a polymath Dubliner only 20 years old arrived in Trieste to teach the burghers English. Svevo, who travelled to England to sell his paint, spoke German and French but little English. It was his and our good fortune that the Berlitz school hired James Joyce, to whom Svevo confess- ed that he too had done a bit of writing. Joyce instantly became Svevo's fan and eventually triumphant protagonist, though the traffic was two-way, with Joyce milking Svevo for the Jewishness of Bloom.

Svevo's apotheosis came a year before his death at a banquet of the PEN Club in Paris to celebrate the publication of The Confessions of Zeno. Livia sat next to Joyce, whose wife was 'delighted to talk in Triestian dialect with me again'.

My first father-in-law, John Strachey, who had taste in all things but did not excel in anything, gave me the G. P. Putnam edition of The Confessions of Zeno more than 30 years ago. From the first paragraph, when our hero, enrolled in a clinic for nicotine addicts, bribes the boot-boy to buy him a packet of cigarettes, to the last, when the planet, bereft of mankind which has destroyed itself, reels off innocently into outer space, I bathed myself in the rare and pleasing flow of his mind. There was not a smidgeon in Svevo of the arrogance or heaviness to be found in Proust or Musil, who were my other heroes. As the book was out of print, I resolved to put it back in, but my produc- tion department — a printer's salesman who came in once a week and got a bottle of whisky for his pains — said the costings did not work. Publishers should not listen to advice. I married my second wife because she said The Confessions of Zeno was her favourite book.

Those who from debility, poverty, in- eptitude or plain indifference will not read this book, a model, in C. P. Snow's phrase, for 'the relatives of good writers', may be compensated by Svevo's account of a meeting between the two giants of 20th- century literature. 'Do you know the Prin- cess X?', asked Proust. 'No', said Joyce, `nor do I want to in the very least.'

Previous page

Previous page