Graham Greene on pseuds

Christopher Hawtree

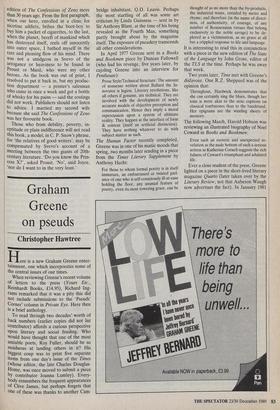

Here is a new Graham Greene enter- tainment, one which incorporates some of the central issues of our times.

When reviewing Greene's recent volume of letters to the press (Yours Etc., Reinhardt Books, £14.95), Richard Ing- rams remarked that it was a pity this did not include submissions to the 'Pseuds' Corner' column in Private Eye. Here then is a brief anthology.

To read through two decades' worth of back numbers (earlier copies did not list Contributor) affords a curious perspective upon literary and social feuding. Who would have thought that one of the most amiable poets, Roy Fuller, should be so assiduous at landing others in it? His biggest coup was to print five separate items from one day's issue of the Times (whose editor, the late Charles Douglas- Home, was once moved to submit a piece by contributor Joanna Lumley). Every- body remembers the frequent appearances of Clive James, but perhaps forgets that one of these was thanks to another Cam-

thought of as no more than the by-products, the industrial waste, entailed by metre and rhyme; and therefore (in the name of direct- ness, of authenticity, of courage, of any number of Rousseauian virtues that belong exclusively to the noble savage) to be de- plored as a victimisation, as no grace at all but a crippled response to life and language.

It is interesting to read this in conjunction with a piece in the new edition of The State of the Language by John Gross, editor of the TLS at the time. Perhaps he was away that week.

Two years later, Time met with Greene's disfavour. One R.Z. Sheppard was of the opinion that:

Throughout, Hardwick demonstrates that she can certainly sing the blues, though her tone is more akin to the stoic captions on classical tombstones than to the bandstand. Her epigrams are the winding sheets of memory.

The following March, Harold Hobson was reviewing an illustrated biography of Noel Coward in Books and Bookmen:

Even such an esoteric and unexpected re- velation as the nude bottom of such a serious actress as Katherine Cornell suggests the rich fulness of Coward's triumphant and adulated life.

Ever a close student of the press, Greene lighted on a piece in the short-lived literary magazine Quarto (later taken over by the Literary Review, not that Auberon Waugh now advertises the fact). In January 1981 bridge inhabitant, Q.D. Leavis. Perhaps the most startling of all was some art criticism by Linda Guinness — sent in by Sir Anthony Blunt, at the time of his being revealed as the Fourth Man, something partly brought about by the magazine itself. The exposure of pseudery transcends all other considerations.

In April 1977 Greene sent in a Books and Bookmen piece by Duncan Fallowell (who had his revenge, five years later, by cajoling Greene into an interview for Penthouse):

Prose Style/Technical Structure: The amount of nonsense written about Ballard the In- novator is legion. Literary revolutions, like all others if genuine, are technical. They are involved with the development of newly accurate models of objective perception and communication. Hence they imply a moral repercussion upon a system of ultimate reality. They happen at the interface of form & content (itself an artificial distinction). They have nothing whatever to do with subject matter as such.

The Human Factor recently completed, Greene was in one of his manic moods that spring, two months later sending in a piece from the Times Literary Supplement by Anthony Hecht:

For those to whom formal poetry is in itself immature, an embarrassed or twisted parl- ance of one who is self-consciously ill-at-ease holding the floor, any unusual feature of poetry, even its most towering grace, can be

playwright Trevor Griffiths wrote: By the early 70s, the disengagement between Tynan and his earliest cultural constituency had all but been effected, though rhetorics endured; and Tynan somehow knew it. By 1975, the Tynan of Two Hands Clapping had dwindled to little more than the untidy sum of his cultural 'enthusiasms', themselves snugly lodged within the accompanying hegemony and of serious concern to nobody. By Show People, as 'late 70s' as almost anything I've read or seen, the disengage- ment has terminated into emigredorn, a disposition of the spirit as much as geog- raphical circumstance, and the long painful declension from autonomy to heteronomy (from, roughly, hierophant to acolyte) fetch- es up at last in the cosmic cultural cul-de-sac of Los Angeles, arguably the worst glimpse of the future the West has yet given' itself.

No ambassador for America, Greene views bad prose with even greater disfavour. Poetry is not exempt, either: in August 1982 he sent in a Sunday Times piece by Christopher Ricks, who began with some lines of Thom Gunn's:

C'mon said the pilot and the three of us climbed onto the wing and into the snug plane.

With a short run we took off, lurched upward, soared, changed direction, missed a treetop, and found an altitude.

Phew, under your breath. The clipped ex- citement is infectious. The title, too, is laconically clipped (the poem 'A Small Plane in Kansas' or 'The. . .'); and then 'C'mon' at once gets cracking with its slurred sober casualness. Then there is the precariousness of 'and' and 'onto' at the ends of the first lines; the pause before take-off, with the full-stop after 'plane', on the runway of its tine; the feeling in the small of the back from the pressure at the start of the line in 'lurched upward'.

Phew, under your breath. Lest all this should appear to be knocking the opposi- tion, one must, alas, conclude with an item from Auberon Waugh's Spectator Wine Club, perhaps the result of too great an enthusiasm for the products he was trying to sell. Greene contented himself with a letter of protest to the magazine (printed in Yours Etc.) but his sister, Elizabeth Dennys, earned a fiver from the Eye for it:

Perhaps I had better introduce it by its smell. Burgundians will recognise it immediately as a smell which sometimes attaches to a very grand, very dusty, slightly sewery smell which I, at any rate, find delicious (knowing what it presages) but non-Burgundians sometimes find disconcerting. My wife, who is no Burgundian, characterises it as the smell of a railway station in a book by Zola.

Perhaps in revenge for this revelation, Teresa Waugh has herself earned a couple of fivers for items clipped from the journal edited by her husband. But any more of this, and one will rival the annotations to the Twickenham Pope.

Previous page

Previous page