Simon Raven on other men's Shakespeare

Shakespeare's Lives S. Schoenbaum (our £6) S. Schoenbaum's purpose, first conceived, as he tells us, in Stratford-upon-Avon, is to present and assess all the biographical materials—whether fact, conjecture, fake or fiction—which attach to the name of Wil- liam Shakespeare.

Of known fact there is, of course, very little, and that little not edifying. Apart from the works themselves and the bare list of dates and names to be found in every stan- dard introduction, about the only things we can be more or less sure•of arc that Shakes- peare's marriage was ill begun and worse continued, and that he was extremely inter- ested in making money, much of which he later invested, like any good bourgeois, in sound properties in his native Stratford. So much is clear enough from the documents adduced by Mr Schoenbaum. To assert that Shakespeare wrote only for money would doubtless be overdoing it; but let nobody think that the Bard was indifferent to the box oflice. To say the very least, he was much concerned about his old age.

Having exhausted what is known in 75 Pages out of over 800, Mr Schoenbaum turns to legend. None of this is very edify- ing either. Shakespeare is alleged to have been an enthusiastic drinker but to have had a weak head, at any rate by the stan- dards of his day. In his early youth he may have been a deer-poacher, and a very clumsy one at that. Possibly he started his career in the theatre by holding horses' heads outside it; perhaps he•had previously been a schoolmaster, and if so he might not have kept his hands very strictly to. himself. Oh dear, oh dear. Is there nothing in all this Which we can pass on with pride, or at least satisfaction, to our starry-eyed sons and daughters?

Well, let's see if the biographers have any- thing to say which might give us heart. Edmond Malone (of the eighteenth century) might have helped, but he failed to finish the course. When we come to the nineteenth cen- tury, we find that biographers and allied workers were either forgers (e.g. Collier), cranks (e.g. Delia Bacon), or, by and large, narcissists. With the first two classes we can have nothing more to do. Of the last we must sadly observe that, while it included many men of talent and repute, its members were all, as the term I have used implies, writing about themselves rather than Shakespeare. For so little was known that they had a prime excuse for conjecture, and hence the temptation to cast the National Poet in their own images was quite irresistible. Thus Bagehot makes the poet out to be a good- humoured and moderate empiricist, loyal to the Crown yet advocating gradual reform. given to -quiet gaiety in public and mild musing melancholy when alone; Wilde pre- sents us with a romantic and passionate pederast: and Samuel Butler. having been roundly fleeced by his own boy-friend Pauli, projects the master as the seedy and guilt- ridden victim of a sexual confidence trick. Of these three portraits. Bagehot's alone might recommend itself to the general appro- bation—and this only because it is really a self-portrait of the civilised and equable Bagehot.

Still, it remains a pleasant picture and offers some comfort to those who would like to think well of their poet. Little such com- fort is to be had from more recent exercises in the game. Of the twentieth-century self- portraits which claim to body forth the Bard, Frank Harris's, needless to say. is randy and paranoiac. Lytton Strachey's bored, waspish and precious, and A. L. Rowse's as podgy and complacent as suet. Of the descriptions which are not self-portraits, John Dover Wilson's1/4(despite the excellence of his criti- cism) reads like the work of an inflamed female novelist; while Anthony Burgess, in his story Nothing Like the Sun, treats us to a Technicolor close-up of the dramatist's secondary syphilis.

And what does Mr Schoenbaum himself make of it all? In some ways he comes out rather well. In the midst of this huge tract of muck and mirage, he keeps his head and his ,sense of direction, and remains quick to spot the true flower among the copious weeds. He uses a steady long-distance prose, which he varies with occasional laconic re- bukes and sly asides; and he is adept at put- ting everybody, from Ben Jonson to Sig- mund Freud. in his proper place.

Everybody, that 'is, except possibly Wil- liam Shakespeare. whose proper place is the tomb in Stratford which he saved so dili- gently to pay for. The minatory words above the gravestone ('And cursed be he that moves my bones') incline one to believe that he wished to stay quiet beneath it; instead of which he has been conjured up, by Mr Schoenbaum's appalling crew of maniac, or fraudulent mediums, and made to flit and gibber through these 800 pages. All in the interest of scholarship, of course, and cer- tainly Mr Schoenbaum tries to make due amends by vigorously, chastising his necro- mantic agents after each of them has done his worst. But will that be enough to lay the poet's ghost? If not, perhaps the celebrated curse will be visited on Mr Schoenbaum by and by. I shall be. most eager to learn what form it takes—in the interest of scholarship, of course.

Simon Raven. author and dramatist, is cur- rently adapting Trollope for BBC television.

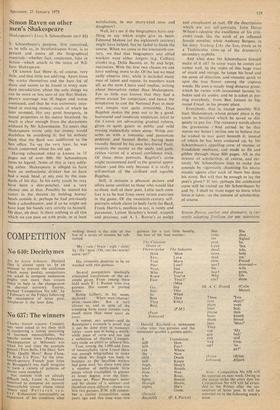

Previous page

Previous page