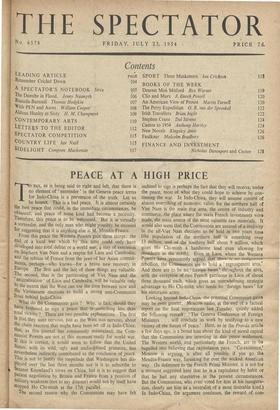

PEACE AT A \ HIGH PRICE T 0 SAY, as is being

said to right and left, that there is no element of ' surrender ' in the Geneva peace terms for Indo-China is a perversion of the truth. Let us be honest. This is a bad peace. It is almost certainly the best peace that could, in the immediate circumstances, be Obtained; and peace of some kind had become a necessity. Therefore, this peace is to be welconied. But it is-virtually a surrender, and the only man who might possibly be excused for suggesting that it is anything else is M. Mendes-France.

From this peace the Western Powers gain three things: the end of a local war which by this time could only have developed into total defeat or a world war: a stay of execution on Southern Viet Nam and a respite for Laos and Cambodia; and the release of France from the jaws of her Asian commit- ments, perhaps—who knows—for a brave new recovery. in EuroPe. The first and the last of these things are valuable. The second, that is the partitioning of Viet Nam and the neutralisation' of Laos and Cambodia, will be valuable only to the extent that the West can use the time between now and the Vietnamese elections to build a strong anti-Communist front behind Indo-China.

What do the Communists gain? Why, in fact, should they have bothered to sign a peace that is something less than total Victory? There are two possible explanations. The first LS that they were nervous, just as the West was nervous, about the chain reaction that might have been set off in Indo-China; that, as this journal has consistently maintained, the Com- luunist Powers are not at this moment ready for world war. If this is correct, it would seem to follow that the United States, with its wild, ugly and undisciplined grimaces, has nevertheless indirectly contributed to the conclusion of peace. This is not to justify the ineptitude that Washington has dis- played over the last three months nor is it to subscribe to Senator Knowland's views on China, but it is to suggest that Patient negotiation by Britain and France from a position of military weakness (not to say disaster) would not by itself have Stopped Ho Chi-minh at the 17th parallel. The second reason why the Communists may have felt inclined to sign is perhaps the fact that they will receive, under the peace, most of what they could hope to achieve by con- tinuing the war. In Indo-China, they will assume control of almost everything of economic value, for the northern half of Viet Nam is the main ric,e area, the centre of industry and commerce, the place where the main French investments were made, the main source of the most valuable raw materials. It would also seem that the Communists are assured of a majority in the all-Viet Nam elections to be held in two years time (the population of the northern half is something over 13 million, and of the southern half about 9 million, which gives Ho Chi-minh a handsome lead even allowing for dissidents in the north). Even in Laos, where the Western ,Powers have persistently argued that Moro rebellion, the Communists are to hold a regroupment area.' And there are to be no foreign bases' throughout the area, with the exception of two French garrisons in Laos .of about three thousand each, Which gives an overwhelming strategio advantage to Ho Chi-minh who needs no 'foreign bases' for his victorious army. Looking beyond Indo-China, the potential Communist gains may be even greater. Moscow radio, at the end of a factual report on the final negotiations last Tuesday, quietly added the following remark: The Geneva Conference of Foreign Ministers . . . will conclude its work by testifying to a new victory of the forces of peace.' Here, as in the Pravda article a few days ago, is a broad hint about the kind of moral capital that the Communists are investing in this peace settlement. The Western world, and particularly the French, are to he beguiled into believing that capitulation pays. 'Co-existence,' Moscow is arguing, is after all possible if you go the Mendes-France way, forsaking for ever the wicked American way. (In deference to the French Prime Minister, it is not for a moment suggested here that he is a capitulator by habit or that he had any alternative in the present circumstances. But the Communists, who even voted for him at his inaugura. tion, clearly see him as a neutralist\of a most desirable kind.) In Indo-China, the argument continues, the reward of con. cessions has been peace. Why not try it in Europe ? Why rearm those dangerous Germans, why pay those taxes, why not indulge your anti-Americanism ? And this rain of triumphant insinuation will come pouring on to well-prepared soil. Europe has never been more eager to believe that the Americans are warmongers to a man (look no further than the British Labour Party); and the Americans have never been louder in their conviction that all Europeans are ready to rat. 'Little nubbins of agreement at conferences in Bermuda and Berlin and Washington must no longer obscure the central fact that for practical purposes the United States stands alone among the great Powers in the cold war '—so runs the latest contribution by the magazine Time to Anglo- American relations.

This is the situation that is the real price of peace in Indo- China. It is a price that, given the French military collapse, the misinformation of France's allies, the confusion in which the Powers went to Geneva, had to be paid. But it will require the concentrated efforts of the leaders of the Western world to wipe out the overdraft that it has created in Western security.

Previous page

Previous page