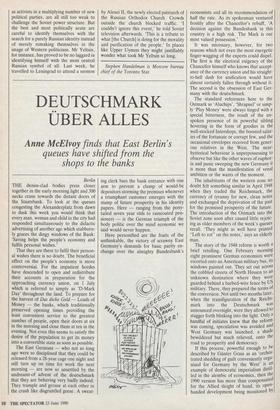

DEUTSCHMARK OBER ALLES

Anne McElvoy finds that East Berlin's

queues have shifted from the shops to the banks

Berlin THE denim-clad bodies press closer together in the early morning light and 300 necks crane towards the distant doors of the Staatsbank. To look at the queues congesting the Alexanderplatz from dawn to dusk this week you would think that every man, woman and child in the city had responded simultaneously to the didactic advertising of another age which stubborn- ly graces the dingy windows of the Bank: `Saving helps the people's economy and fulfils personal wishes.'

That they are there to fulfil their person- al wishes there is no doubt. The beneficial effect on the people's economy is more controversial. For the impatient hordes have descended to open and redistribute their accounts in preparation for the approaching currency union, on 1 July which is referred to simply as 'D-Mark Day' throughout the land. To prepare for the harvest of Das dicke Geld — Loads of Money — the banks, which traditionally preserved opening times providing the least convenient service to the greatest number of people, open their doors at six in the morning and close them at ten in the evening. Not even this seems to satisfy the desire of the population to get its money into a convertible state as soon as possible. The East Germans — who not so long ago were so disciplined that they could be released from a 28-year cage one night and still turn up on time for work the next morning — are now so unsettled by the undreamt-of advent of the deutschmark that they are behaving very badly indeed. They trample and grouse at each other in the crush like disgruntled geese. A sweat-

ing clerk bars the bank entrance with one arm to prevent a clump of would-be depositors storming the premises whenever a triumphant customer emerges with the stamp of future prosperity in his identity papers. Here — ranging from the pony- tailed seven year olds to raincoated pen- sioners — is the German triumph of the body politic over the mind economic we said would never happen.

Here personified are the fruits of the unthinkable, the victory of scrawny East Germany's demands for basic parity ex- change over the almighty Bundesbank's economists and all its recommendation of half the rate. As its spokesman ventured frostily after the Chancellor's rebuff, 'A decision against the Bundesbank in this country is a high risk. The Mark is our most valued possession.'

It was necessary, however, for two reasons which not even the most energetic finger-wagging of the experts could dispel. The first is the electoral exigency of the Chancellor himself who knows that accept- ance of the currency union and his straight- to-hell dash for unification would have almost certainly fallen through without it. The second is the obsession of East Ger- many with the deutschmark.

The standard references here to the Ostmark as `Aluchips', 'Shrapnel' or simp- ly 'Play Money' were always tinged with a special bitterness, the result of the un- spoken presence of its powerful sibling hovering in the form of goodies in the well-stocked Intershops, the boosted salar- ies of the fortunate or corrupt few, and the occasional envelopes received from gener- ous relatives in the West. The near- hysterical behaviour is unprepossessing to observe but like the other waves of euphor- ia and panic sweeping the new Germany it is more than the manifestation of venal ambition or the wants of the moment.

The inhabitants of the western zone no doubt felt something similar in April 1948 when they traded the Reichsmark, the currency of tyranny for new, clean notes and exchanged the deprivation of the past for the promised prosperity of the future. The introduction of the Ostmark into the Soviet zone soon after caused little rejoic- ing as older members of the week's queues recall. 'They might as well have printed "Left to rot" on the notes,' says an elderly man.

The story of the 1948 reform is worth a brief retelling. One February morning eight prominent German economists were escorted onto an American military bus, its windows painted out. They set out across the cobbled streets of North Hessen to an unknown destination where they were guarded behind a barbed-wire fence by US military. There, they prepared the terms of the conversion. Not until two months later, when the transfiguration of the Reichs- mark into the Deutschmark was announced overnight, were they allowed to stagger forth blinking into the light. Only a handful of initiates knew that the reform was coming, speculation was avoided and West Germany was launched, a shade bewildered but much relieved, onto the road to prosperity and democracy. If this process, powerful enough to be described by Giinter Grass as an 'orches- trated shedding of guilt conveniently orga- nised for Germany by the West' is an example of democratic imperialism distil- led in the alembic of economics, then the 1990 version has more than compensated for the Allied sleight of hand, its open- handed development being monitored by the suspicious German electorates East and West.

Neither economist, housewife nor obser- ver can calculate the consequences of D-Mark Day. The likely victor at the moment is the Chancellor himself but even he is aware that it could turn into a Pyrrhic one as inflation and unemployment — as the economists warned — inevitably start to breath down the necks of the happy July shoppers. Since the move was announced they have been giving domestic products a wide berth in preparation for their onslaught onto the department stores of the West. The moribund pollutant industry belt of Bitterfeld, Leipzig and Halle (known to its inhabitants for good reason as Die Mille —hell) will be the first casualties along with the 'social peace' in their communities. The trade unions, aroused from the anaesthetised existence of 40 years are beginning to find their voices and their support again, and will no doubt gain in confidence once the work- force experiences at first hand that the average East German wage of 900 Marks (£330) is scant provision for fulfilling con- sumerist dreams. It will be a long hot autumn on the shop floors of the East.

Avant le deluge, however, the dissolving socialist state on German soil, its ideology as devalued as its currency, fidgets towards the July bonanza in heady anticipation of its one-to-one trade-in and the instant happiness of Kaufwut. Any West Berliner planning on acquiring a washing machine or video recorder had better move fast.

We who have lived a double life here cushioned by our hard currency but treat- ing ourselves to the complete works of Lenin and the motley alcoholic produce 'of the friendly countries' at the seesawing rates of the Ostmark will be sad to see it go, a regret completely incomprehensible to the natives. Auf nimmer Wiedersehen then to the grave mien of Karl Marx etched in incongruous baby-blue on the prettiest of monopoly monies. Time to launch fran- tic searches through filing cabinets and down the back of the sofa for the minor hoards put by hamster-like for emergen- cies, and about to be relegated to the status of bookmarks, if we do not join the queues in time.

Welcome instead to the belated fulfil- ment of Goethe's vision, 'that the Thaler and Groschen should have the same worth in the whole kingdom', to the confident jangle in pockets which a friend once remarked 'made even the poorest Wessi sound like a millionaire in the East', to bank robberies which until now were not even considered worth the outlay for a Balaclava, to the mystical, unpredictable power of the Mark, the coin of reconstruc- tion, overburdened harbinger of unity and, as of D-Mark Day, the German measure of most things.

Previous page

Previous page