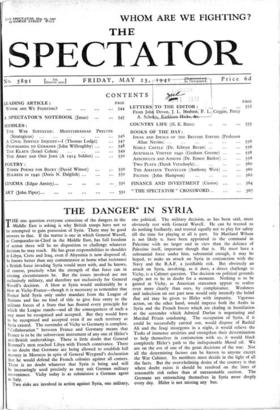

THE DANGER . IN SYRIA T HE one question everyone conscious of

the dangers in the Middle East is asking is why British troops have not so far attempted to gain possession of Syria. There may be good answers to that. If the matter is one in which General Wavell, as Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, has full freedom of action there will be no disposition to challenge whatever decision he may reach. He has great responsibilities to shoulder in Libya, Crete and Iraq, even if Abyssinia is now disposed of, he knows better than any commentator at home what resistance a British force invading Syria would meet with, and he knows, of course, precisely what the strength of that force can in existing circumstances be. But the issues involved are not exclusively military, and therefore not exclusively for General Wavell's decision. A blow at Syria would undeniably be a blow at Vichy-France—though it is necessary to remember that France held Syria only under mandate from the League of Nations and has no kind of title to give free entry to the militant forces of a State that has flouted every principle for which the League stands—and all the consequences of such a step must be recognised and accepted. But they would have to be recognised and accepted even if no such territory as Syria existed. The surrender of Vichy to Germany is complete.

" Collaboration " between France and Germany means that France is to be the subservient instrument of any one of Hitler's anti-British undertakings. There is little doubt that General Rommel's men reached Libya with French connivance. There is no doubt that Germans are being allowed to establish full mastery in Morocco in spite of 'General Weygand's declaration that he would defend the French colonies against all comers. There is no doubt whatever that Syria is being and will be increasingly used precisely as may suit German military convenience. Vichy today is as submissive a German agent as Italy.

Two risks are involved in action against Syria, one military, one political. The military decision, as has been said, must obviously rest with General Wavell. He can be trusted to do nothing foolhardy, and trusted equally not to play for safety till the time for playing at all is past. Sir Maitland Wilson is not likely tc have been appointed to the command in Palestine with no larger end in view than the defence of Palestine itself, important though that is. He must have a substantial force under him, substantial enough, it may be hoped, to make an attack on Syria in conjunction with the Navy and the R.A.F. a justifiable risk. But obviously an attack on Syria, involving, as it does, a direct challenge to Vichy, is a Cabinet question. The decision on political grounds ought not to be in doubt for a moment. Nothing is to be gained at Vichy, as American statesmen appear to realise even more clearly than ours, by complaisance. Weakness and indecision on our part now would only intensify the belief that aid may be given to Hitler with impunity. Vigorous action, on the other hand, would impress both the Arabs in Syria and the French forces which are chafing in humiliation at the surrender which Admiral Darlan is negotiating and Marshal Petain condoning. The occupation of Syria, if it could be successfully carried out, would dispose of Rashid Ali and the Iraqi insurgents in a night, it would relieve the Turks of immense anxieties and strengthen their determination to help themselves in conjunction with us, it would block completely Hitler's path to the indispensable Mosul oil. We are on the eve of one of the great decisions of the war. Not all the determining factors can be known to anyone except the War Cabinet. Its members must decide in the light of all the facts. But the overwhelming desire of the country is that where doubt exists it should be resolved on the lines of reasonable risk rather than of unreasonable caution. The Germans are entrenching themselves in Syria more deeply every day. Hitler is not missing any bus.