The latest corpses

Richard West

Guatemala City Some of the journalists in El Salvador assured me that 'Guatemala's twice as sinister, . That's where the war will really break out . . . That's the new Vietnam'. Certainly Guatemala, the largest in population (8 million) of all the Central American countries, has more of a reputation than most for political turmoil and carnage. There is still, in progressive north London, a slogan 'HANDS OFF GUATEMALA!' which dates to the coup d'etat of 1954, when the CIA engineered the overthrow of the left-wing President Arbenz. The Arbenz government had expropriated the land of the United Fruit Company, whose influence in these parts had given to Guatemala and other Central American states the nickname 'Banana Republics'. The coup became still more unpopular when it was learned that the US Secretary of State at the time, John Foster Dulles, had been one of the law firm that drew up the United Fruit Company's post-war agreement with Guatemala; while his brother Allen Dulles, then head of the CIA, was a former UFC President.

Guatemala came back in the news in 1962, when it was used as a base for the army of anti-Castro Cubans who made the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs invasion. President Kennedy authorised this deal with the Guatemalan government, although in public disapproving of certain things in this country. Although never much in the news, Guatemala retained a dour, sinister reputation. Earthquakes have pulled down its cities. The Indians, who form half the population, have frequently risen and been put down, amidst rumours of massacre. Travel around the country has. often been restricted by curfew or by outright prohibition. Even entry into the country has been forbidden to people with long hair, Negroes or those with Communist stamps in their passports. The British were banned for a time because of Guatemala's claim to British Honduras. Now the British, especially the Anglo-French grocer and litigant, Sir James Goldsmith, are prominent in the exploitation of Guatemala's promising oil reserves.

Guatemala City gives little impression of civil strife; less than El Salvador; far less than Belfast. It is safe, and indeed very pleasant to live in the downtown district, in a boarding house, rather than seeking refuge in one of the big hotels on the outskirts. The military are around but they are not oppressive. There is no curfew at night, as there is in El Salvador — where anyone on the street after 10 pm is shot dead. The guerrillas have not yet planted bombs in the cinemas — as they do in San Salvador. The conversation in bars is friendly if rather lugubrious: 'Are you not frightened to come to Guatemala? [said ironically] with all our shootings? But what do you expect of Latin America? And all countries have their problems even yours . . . With the blacks and the Irish'. (One San Salvador paper when I was there carried a story headlined 'Deterioration of British Police' and a claim that plain clothes men in Brixton has used 'tactics which they had learned from American TV films'.) In Guatemala, more than in most Latin American countries, one must remember how ancient and therefore insoluble are its troubles, its wars and injustices. Here, as in southern Mexico and Belize, one can see the remains of the cities built by the Mayan rulers before they too were destroyed by war with other Amerindian people. Civilisation here was in decay when the Spanish arrived in Central America, searching for gold, silver, or slaves to work the plantations. The ferocious cruelty of the Span iards helped to produce the authoritarian social system, tempered by apathy and by violent revolt, that persists in all those parts of America where Indian people exist with people of Spanish origin. The Spanish regime produced also the wonderful city of Antigua, 18 miles from here, founded in 1543, and for a long time the cultural centre of all Central America, with its university, its great churches and many famous writers, scholars and artists. But a number of earthquakes, the worst in 1976, have turned Antigua into a ruin, like one of the Mayan cities. One of the few churches left almost undamaged is that of Fr Bartolome de las Casas, the 16th century priest who almost alone condemned the massacre and enslavement of native American people.

Antigua is now a centre of Indian handicrafts, for teaching Spanish to foreigners, and of course for tourists — many of whom are young North American 'backpackers', wearing the long hair and scruffy clothes that cause such annoyance to Guatemalan frontier officials. Because Antigua is (as the word means) old, or antique, the North Americans appear as foreign and out of place as they would in Spain itself. You see very distinctly the contrast between the Yanqui and SpanishIndian cultures.

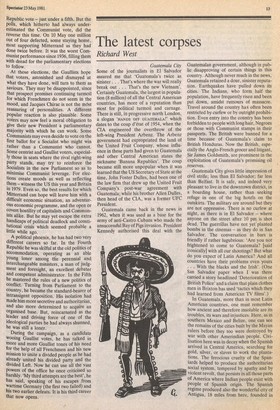

The local newspapers show this still more clearly. One day I noticed a tabloid, Sucesos, whose front page consists of two pictures of corpses — one of them seemingly headless and blackened by flame. These, so the headline said, were some of the victims of last week's murders. I bought Sucesos and found that each of its 16 pages consisted of nothing but photographs from the morgues or scenes of the murder, plus gruesomely jocular captions: 'It seems that the authors of these acts have in their pockets plenty of ammunition for they leave every victim drilled through like a rifle range target — at least 20 or 25 bullets in every corpse. Perhaps they were making sure of death'. The captions assume that all these bodies were victims of 'politics', meaning insurgents, though no one could indentify most of the faces. But I do not suppose that Sucesos is published as propaganda. It sells on its merits. And what kind of people will spend money on 16 pages of photographs of the latest corpses?

In talking of places like Guatemala and El Salvador, of ideological clashes and big power rivalry, we tend to forget that these countries are still quite close to the Central America that we know from the cinema and from legend — the firing squads in the courtyard, the peasants in wide-brimmed hats engaged in ferocious battle with goldtoothed, unshaven and bestially cruel soldiers. That is essentially a caricature of Mexico in the early part of the century; but even the caricature is more like Guatemala today than most of the earnest reports we hear of democratic elections, land reform and socialist planning. The political slogans change, but Guatemala does not.

On this journey, I have been re-reading Joseph Conrad's Latin America novel Nostromo (published in 1917) and I find that nothing he wrote of the horrors then is out of place today. The country he describes is called Costaguana — a parrot is taught to cry `Viva Costaguana!' — with a population of Spanish, Indians and Negroes, or mixtures of all three, and with coasts on both the Atlantic and Pacific. The politics of the country are well summed up by one of the older characters who has written a history of Costaguana entitled Fifty Years of Misrule, a book which in view of the constant political turmoil `he thought it was prudent "not to give to the world" In one of the many civil wars between Whites ahd Reds, there was a wholesale massacre of the Aristocratic Club ('their bodies were afterwards stripped naked and flung into the plaza out of the windows by the lowest scum of the population'), while the dictator Guzman, carried about, at the tail of his Army of Pacification, 'a company of nearly naked skeletons, loaded with irons . . . The irregular report of the firing squad could be heard, followed sometimes by a single finishing shot; a little bluish cloud would float above the green bushes, and the Army of Pacification would move on over the savannas, through the forest, crossing rivers, invading rural pueblos, devastating the haciendas of the horrid aristocrats, occupying the inland towns in the fulfilment of its patriotic mission . .

American capitalism had not yet come to the country. 'What is Costaguana?' asks, rhetorically, one of the US financial potentates. 'It is the bottomless pit of ten per cent loans and other fool investments. European capital has been flung into it with both hands for years. Not ours, though . . . Time itself has got to wait on the greatest country in the whole of God's Universe'. It is an Englishman, Sir John, who opens the Costaguanan railways; and the hero James Gould who risks his all on the silver mine.

Those people who search in Guatemala and El Salvador for 'America's new Vietnam' seem to forget that Latin America and its problems are nothing new to a Washington government; they have been there since the United States began and for 250 years before. The present involvement of the United States in Central America is not as serious or as deep as it was in Mexico throughout the 19th century and up to the second world war. Even the Communist Russian threat is not such a novelty as one might assume from hearing the speeches of' such as General Haig.

It was not General Haig who announced: 'The Bolshevist leaders have set up as one of their fundamental tasks the destruction of what they term American imperialism as a necessary prerequisite to the successful development of the international revolutionary movement in the New World'. That was the US Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg addressing the Senate in 1927.

Perhaps the United States should not demand too much decency from its Central American allies; not try to install liberal governments; not try, in Woodrow Wilson's phrase, 'to teach South American republics to elect good men'. The much wiser Democrat President Franklin D. Roosevelt said of Trujillo, the vile dictator of the Dominican Republic: 'He's a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch'.

Previous page

Previous page