Making books out of bits of books

Tom Shone

When a star nears the end of its life, Albert Einstein suggested, it collapses, its radius becoming smaller and smaller until it reaches the state of a dimensionless point, a black hole. Paradoxically, having attained this uniquely vacuous state it develops an unstaunchable appetite for sucking up and devouring any surrounding matter.

So too with anthologies. For recent years have shown that there is a similar inverse ratio between the ever-smaller area of human activity that has not yet been anthologised and the number of antholo- gies it seems to attract. And so we have had two books of the Sea, Writers on War three times, Love Poetry twice; two Feuds are brewing, another Gay Short Fiction to keep the existing one company, and both Claire Tomalin and Michael Rosen are at present bearing down on the still tranquil oasis of Childhood.

'There is no stopping the flow,' com- plained Eric Christiansen in the Indepen- dent last year, in more Newtonian terms:

The Christmas trees, the lavatory shelves and the bedside tables of Britain bay their challenge to the publishers.

Even D. J. Enright — who has worked through Illness (Faber) and Death (Oxford) and now proceeds to clean up beyond the pale, with The Oxford Book of the Supernatural — says of the current anthology-boom:

I used to think of editing anthologies as a sort of curatorship, digging up lesser known pieces of literature which the public might not know. I wonder if it isn't being overdone now: they're working that particular golden goose to death.

Penguin and Oxford University Press have long published anthologies for aca- demic consumption. But aside from the odd public ruckus such as that between Leavis and Arthur Quiller-Couch over the latter's Oxford Book of English Verse in 1926 this tinkering went quietly, muffled by the library stacks. OUP didn't realise the trade potential of popular anthologies until relatively recently. The Oxford Book of Lit- erary Anecdotes, edited by James Suther- land in 1975, was the first anthology to achieve bestseller status and spawned a brood of similar anecdote anthologies. OUP then proceeded with Sleep and Death, and were followed in the mid-Eighties by Faber — helped by their massive poetry backlist — later by Chatto & Windus, and most recently by Penguin.

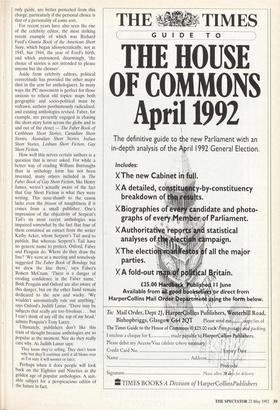

'The canonical anthologies of various lit- erary forms have been compiled and recompiled,', says Francis Spufford, editor of The Chatto Book of Lists and the forth- coming Chatto Book of the Devil, 'and the only new ground to break is with thematic anthologies, which are getting weirder and weirder'. The Chatto Book of Lists is an excellent example of the new type of 'thematic' anthology: taking a geological slice beneath the traditional generic hedgerow, its more than ordinarily eclectic editorial stance is embodied in its winding full title, The Chatto Book of Cabbages and Kings (a trend followed by The Faber Book of Fevers and Frets, and, perhaps making up for lost time with an extra adjective and noun, The Penguin Book of Fights, Feuds and Heartfelt Hatreds).

Unfortunately, these rich if thin seams are proving fewer and further between. The final product of one publisher's brain- storming session is, with increasing regular- ity, turning out to be identical to the next. 'There is a sort of tide at work,' says Chat- to's Jonathan Burnham, 'great minds think alike.' Particularly if they are at work on the same square inch of unanthologised material.

As Simon Brett, editor of The Faber Books of Diaries, Useful Verse and Parodies. says:

The lifespan of these anthologies is not as long as it was, so publishers can wait a few years until people forget about it and bring out another on the same subject.

Publishers' opinion of the general public's memory capacity is evidently dim. For while Faber jettisoned its load of Blue Verse before Fiona Pitt-Kethley's Literary Companion to Sex even got started, in 1990 John Fuller's Chatto Book of Love Poetry achieved mutual climax with The Virago Book of Love Poetry edited by Wendy Mulford. 'We were worried about their simultaneous publication,' says Burnham, 'and conferred with Virago, but decided that the market could support two. We were borne out by sales'.

As with black holes, nobody is quite sure what happens to this reading matter once it has been sucked in. All publishers know is that they sell well, particularly in the run- up to Christmas. As OUP's Judith Lunar says: 'You don't need to know the taste of someone particularly well to give them an anthology.' Which suggests that they end up in that strange twilight dimension that exists between what publishers think the public wants to buy and what a certain sec- tion of the public buys in the hope that it is what the other half wants to read.

And so the publishers keep piling them on. It is not hard to see why: anthologies are relatively quick and easy to produce, don't require anybody to actually write them and, if not bestsellers, they sell plod- dingly well. The popular, 'thematic' anthologies have an added bonus. Antholo- gies which claim to be authoritative are open to the criticism that they are not. On the other hand, anthologies which investi- gate areas on to which the idea of a 'canon' has never previously encroached — like sleep, office life, death — and in which the editor's own personal enthusiasm is the only guide, are better protected from this charge, particularly if the personal choice is that of a personality of some sort.

For recent years have also seen the rise of the celebrity editor, the most striking recent example of which was Richard Ford's Granta Book of the American Short Story, which began idiosyncratically, not at 1945, but 1944, the year of Ford's birth, and which announced, disarmingly, 'the choice of stories is not intended to please anyone but the chooser'.

Aside from celebrity editors, political correctitude has provided the other major shot in the arm for anthologisers. In many ways the PC movement is perfect for those anxious to reheat old topics: maps both geographic and socio-political must be redrawn, authors posthumously radicalised, and existing anthologies revised. Faber, for example, are presently engaged in chasing the short story form across the globe and in and out of the closet — The Faber Book of Caribbean Short Stories, Canadian Short Stories, Australian Short Stories, Indian Short Stories, Lesbian Short Fiction, Gay Short Fiction.

How well this serves certain authors is a question that is never asked. For while a better way of reading William Burroughs than in anthology form has not been invented, many others included in The Faber Book of Gay Short Fiction, like Henry James, weren't actually aware of the fact that Gay Short Fiction is what they were writing. This nose-thumb to the canon lacks even the frisson of naughtiness if it comes from a small publisher. One's impression of the objectivity of Serpent's Tail's six most recent anthologies was impaired somewhat by the fact that four of them contained an extract from the writer Kathy Acker, whom Serpent's Tail used to publish. But whereas Serpent's Tail have no generic name to protect, Oxford, Faber and Penguin do. Where do they draw the line? 'We were at a meeting and somebody suggested The Faber Book of Bondage but we drew the line there,' says Faber's Robert McCrum. 'There is a danger of eroding confidence in the Faber name.' Both Penguin and Oxford are also aware of this danger, but on the other hand remain dedicated to the new and wacky. 'We wouldn't automatically rule out anything,' says Oxford's Judith Lunar. 'There may be subjects that really are too frivolous ... but I can't think of any off the top of my head,' admits Penguin's Tony Lacey.

Ultimately, publishers don't like this train of thought because anthologies are so popular at the moment. Nor do they really care why. As Judith Lunar says:

They know they're selling. Thcy don't know why but they'll continue until it all blows over as I'm sure it will sooner or later.

Perhaps when it does people will look back on the Eighties and Nineties as the golden age of popular anthologies. A suit- able subject for a perspicacious editor of the future in fact.

Previous page

Previous page