Exhibitions 1

Treasures of a Polish King: Stanislaus Augustus as Patron and Collector (Dulwich Picture Gallery, till 26 July)

Vaut le detour

David Ekserdjian

Loan exhibitions of old masters are out of favour among the bien-pensants these days. They are both pointless and danger- ous, we are told, usually by those most inclined to visit them. This is to deny the self-evident illumination afforded by the juxtaposition of two or more related but far-flung works of art. Furthermore, it is suggested that people, who are after all

more expendable than paintings, should be made to do the travelling if they want to see a particular masterpiece. Again, this bleat is invariably mouthed by the happy few who have the money, time and oppor- tunity to roam the globe in pursuit of great art. However true it is that the two Bellot- tos loaned to this exhibition look better in Warsaw, the observation ignores the practi- cal difficulty of getting there. The truth is that it is hard enough luring the punters out to leafy Dulwich — although with luck a special bus link from central London for the duration of the show will do the trick.

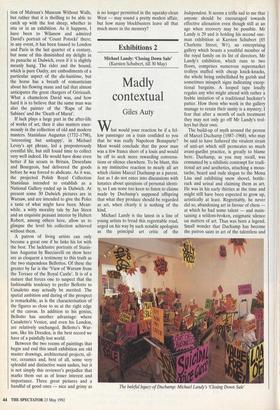

The ultimate fame of works of art is inti- mately linked to their final resting-places. Titian's 'Flaying of Marsyas' in Kromeriz was largely unknown until the Royal Academy's Genius of Venice exhibition. Similarly, Leonardo's 'Lady with an Ermine' is bound to be less celebrated than the notably less sheerly beautiful Mona Lisa simply because it lives in the Czarto- ryski Museum in Cracow — which is not to say that all our treasures should be pooled together in some ghastly concrete realisa- 'Choice Between Youth and Wealth, 1625-6, by Jan Steen tion of Malraux's Museum Without Walls, but rather that it is thrilling to be able to catch up with the lost sheep, whether in situ or in an exhibition. As it happens, I have been to Wilanow and admired David's portrait of 'Count Potocki' there; in any event, it has been loaned to London and Paris in the last quarter of a century, but none of this diminished my delight in its panache at Dulwich, even if it is slightly meanly hung. The rider and the hound, which is pure Oudry, are embodiments of a particular aspect of the dbc-huitieme, but the horse has a breath of romanticism about his flowing mane and tail that almost anticipates the great chargers of Gdricault. What a chameleon David was, and how hard it is to believe that the same man was also the painter of the 'Rape of the Sabines' and the 'Death of Marat'.

If luck plays a large part in the after-life of works of art, then it also matters enor- mously in the collection of old and modern masters. Stanislaus Augustus (1732-1798), `interesting but unhappy', in Michael Levey's apt phrase, led a preposterously eventful life, but still found time to collect very well indeed. He would have done even better if his scouts in Britain, Desenfans and Bourgeois, had delivered the goods before he was forced to abdicate. As it was, the projected Polish Royal Collection Stanislaus intended to establish as a National Gallery ended up in Dulwich. At present some 30 Dulwich pictures are in Warsaw, and are intended to give the Poles a taste of what might have been. Mean- while, a witty morality tale by Jan Steen and an exquisite peasant interior by Hubert Robert, among others here, allow us to glimpse the level his collection achieved without them.

A patron of living artists can only become a great one if he links his lot with the best. The lacklustre portraits of Stanis- laus Augustus by Bacciarelli on show here are as eloquent a testimony to this truth as the two stupendous Bellottos. Of these the greater by far is the 'View of Warsaw from the Terrace of the Royal Castle'. It is of a stature that forces one to suspect that the fashionable tendency to prefer Bellotto to Canaletto may actually be merited. The spatial ambition and daring of the prospect is remarkable, as is the characterisation of the figures so close to us at the right edge of the canvas. In addition to his genius, Bellotto has another advantage: where Canaletto's Venice, and even his London, are relatively unchanged, Bellotto's War- saw, like his Dresden, is the best record we have of a painfully lost world.

Between the two rooms of paintings that begin and end this small exhibition are old master drawings, architectural projects, sil- ver, ceramics and, best of all, some very splendid and distinctive waist sashes, but it is not simply this reviewer's prejudice that marks them out as of lesser interest and importance. Three great pictures and a handful of good ones — nice and grimy as is no longer permitted in the squeaky-clean West — may sound a pretty modest affair, but how many blockbusters leave all that much more in the memory?

Previous page

Previous page