Exhibitions 2

Madly contextual

Giles Auty

hat would your reaction be if a fel- low passenger on a train confided to you that he was really Napoleon Bonaparte? Most would conclude that the poor man was a few francs short of a louis and would be off to seek more rewarding conversa- tions or silence elsewhere. To be blunt, this is my instinctive reaction to nearly all art which claims Marcel Duchamp as a parent. Just as I do not enter into discussions with lunatics about questions of personal identi- ty, so I am none too keen to listen to claims made by Duchamp's supposed offspring that what they produce should be regarded as art, when clearly it is nothing of the kind.

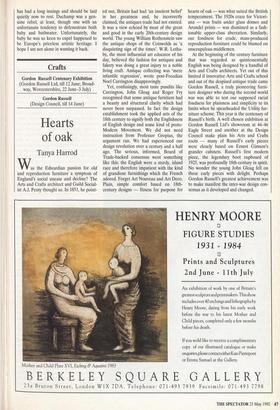

Michael Landy is the latest in a line of young artists to tread this regrettable road, urged on his way by such notable apologists as the principal art critic of the Independent. It seems a trifle sad to me that anyone should be encouraged towards effective alienation even though still at an age when recovery may be possible. Mr Landy is 29 and is holding his second one- man exhibition at Karsten Schubert (85 Charlotte Street, W1), an enterprising gallery which boasts a youthful member of the royal family on its list of directors. Mr Landy's exhibition, which runs to two floors, comprises numerous supermarket trolleys stuffed with cheap knick-knacks, the whole being embellished by garish and sometimes misspelt signs indicating excep- tional bargains. A looped tape loudly regales any who might attend with rather a feeble imitation of a traditional huckster's patter. How those who work in the gallery manage to retain their sanity is a mystery; I fear that after a month of such treatment they may not only go off Mr Landy's trol- leys but their own.

The build-up of myth around the person of Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968); who may be said to have fathered the virulent strain of anti-art which still permeates so much avant-gardist practice, is greatly to blame here. Duchamp, as you may recall, was consumed by a nihilistic contempt for tradi- tional art and aesthetics, attaching a mous- tache, beard and rude slogan to the Mona Lisa and exhibiting snow shovel, bottle- rack and urinal and claiming them as art. He was in his early thirties at the time and might still have been expected to grow up, artistically at least. Regrettably, he never did so, abandoning art in favour of chess at which he had some talent — and main- taining a seldom-broken, enigmatic silence on matters of art. Thus was born a legend. Small wonder that Duchamp has become the patron saint in art of the talentless and

The baleful legacy of Duchamp: Michael Landy's 'Closing Down Sale' disaffected — who are legion, in present- day art schools especially. What is perhaps Duchamp's most famous work, 'The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even', comes over as a comment on sexual impo- tence and human futility. Duchamp hardly had a word to utter on art that was posi- tive. As the eminent French critic Helene Parmelin remarked perceptively: 'There has never been a great creator, never been a great master who has thought in terms of refusal, or nay-saying'.

A general fear among critics to regard works by supposed followers of Duchamp simply as empty gestures stems largely from fear of taking on the inflated reputa- tion of the old chess-player himself. Duchamp is the effective father of the ignorant hatred, commonly encountered now in certain influential sections of the art world, for aesthetic principles of any kind, beauty or skilled execution. In short, Duchamp's influence on subsequent gener- ations, intended or otherwise, has been deeply life-diminishing. To cite merely one example, few of his disciples ever manage to experience the inherent human satisfac- tion arising from creating significant works of art, as such an expression would have been understood by past masters. This is their and our immeasurable loss.

Should you go to see the exhibition at Karsten Schubert, I imagine you, too, may wonder why passionate proponents of neo- Dadaist, conceptual and anartist works — I think especially here of the principal critics of the Independent and Time Out — have such a profound psychological need to defend the indefensible. I can but imagine they live still in an imagined world of besieged Bohemia, never noticing that everything they campaign for is venerated already in the intellectually vacuous muse- um culture of the West. The fact that both can be relied on to find good to say about artefacts which have nothing apparent to recommend them is the likely reason why this pair has been chosen as the last two critic-jurors on the panel to decide the des- tination of the Turner Prize. By picking the right jury, the continuation of an avant- gardist stranglehold at the centre of con- temporary visual culture can be more or less guaranteed. The Turner Prize remains an ill-conceived attempt to reward notions of artistic radicalism which are already 70 years out of date.

It has been suggested that Mr Landy's art, which is on sale, incidentally, at £1,200 per trolley-load and £35.95 per hand- written sign, is an ironic comment on con- sumer society. As ever, it can only be con- text which could make it so. I am sure you are familiar with the argument that what may look like rubbish on the street becomes transformed contextually the moment it enters an art gallery. In short, you are asked to suspend the judgment of your eyes and other senses; perhaps your fellow passenger was Napoleon after all? The old, Duchampian pseudo-philosophy has had a long innings and should be laid quietly now to rest. Duchamp was a gen- uine rebel, at least, though one with an unfortunate tendency to defenestrate both baby and bathwater. Unfortunately, the baby he was so keen to expel happened to be Europe's priceless artistic heritage. I hope I am not alone in wanting it back.

Previous page

Previous page