Crafts

Gordon Russell Centenary Exhibition (Gordon Russell Ltd, till 12 June; Broad- way, Worcestershire, 22 June-3 July)

Gordon Russell (Design Council, till 14 June)

Hearts of oak

Tanya Harrod

Was the Edwardian passion for old and reproduction furniture a symptom of England's social unease and decline? The Arts and Crafts architect and Guild Social- ist A.J. Penty thought so. In 1851, he point-

ed out, Britain had had 'an insolent belief' in her greatness and, he incorrectly claimed, the antiques trade had not existed. It was a view echoed by most of the great and good in the early 20th-century design world. The young William Rothenstein saw the antique shops of the Cotswolds as 'a disquieting sign of the times'. W.R. Letha- by, the most influential art educator of his day, believed the fashion for antiques and fakery was doing a great injury to a noble living craft. Antique collecting was 'mere infantile regression', wrote post-Freudian Noel Carrington disapprovingly.

Yet, confusingly, most taste pundits like Carrington, John Gloag and Roger Fry recognised that some antique furniture had a beauty and structural clarity which had never been surpassed. In fact the design establishment took the applied arts of the 18th century to signify both the Englishness of English design and some kind of proto- Modern Movement. We did not need instruction from Professor Gropius, the argument ran. We had experienced our design revolution over a century and a half ago. The serious, informed, Board of Trade-backed consensus went something like this: the English were a sturdy, island race and therefore impatient with the kind of grandiose furnishings which the French adored. Forget Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Plain, simple comfort based on 18th- century designs — fitness for purpose for hearts of oak — was what suited the British temperament. The 1920s craze for Victori- ana — wax fruits under glass domes and Arundel prints — was dismissed as a fash- ionable upper-class aberration. Similarly, our fondness for crude, mass-produced reproduction furniture could be blamed on unscrupulous middlemen.

At the beginning of the century furniture that was regarded as quintessentially English was being designed by a handful of Arts and Crafts architects. Yet out of this limited if innovative Arts and Crafts school and out of the despised antique trade came Gordon Russell, a truly pioneering furni- ture designer who during the second world war was able to test our supposed racial fondness for plainness and simplicity to its limits when he spearheaded the Utility fur- niture scheme. This year is the centenary of Russell's birth. A well chosen exhibition at Gordon Russell Ltd's showroom at 44-46 Eagle Street and another at the Design Council make plain his Arts and Crafts roots — many of Russell's early pieces were closely based on Ernest Gimson's grander cabinets. Russell's first modern piece, the legendary boot cupboard of 1925, was profoundly 18th-century in spirit. No wonder the young John Gloag fell on these early pieces with delight. Perhaps Gordon Russell's greatest achievement was to make manifest the inter-war design con- sensus as it developed and changed.

His story is a romantic one, a mixture of George Gissing and News From Nowhere. As a young boy he lived in an 'ugly monotonous little suburban home' in Toot- ing. Thanks to his father's own romanticism he was transported from this desert to Broadway in the Cotswolds to be surround- ed by beauty and tradition. His father was an artistic bank clerk turned artistic inn- keeper and by 1914, when he joined the army, the son was a dabbler in antiques turned furniture designer. Broadway and the remains of C.R. Ashbee's community at Chipping Campden educated him visually and between 1919 and 1929 Gordon Rus- sell poured forth a stream of Arts and Crafts-inspired designs for furniture and metalwork. He employed local men and the business traded as The Russell Work- shops — a picturesque name with an Art Worker's Guild flavour.

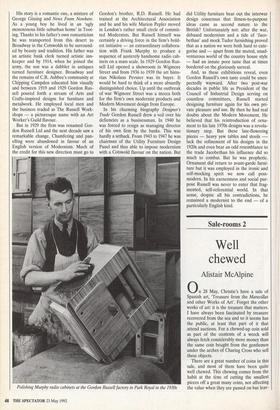

But in 1929 the firm was renamed Gor- don Russell Ltd and the next decade saw a remarkable change. Chamfering and pan- elling were abandoned in favour of an English version of Modernism. Much of the credit for this new direction must go to Gordon's brother, R.D. Russell. He had trained at the Architectural Association and he and his wife Marion Pepler moved in London's rather small circle of commit- ted Modernists. But Russell himself was certainly a driving force in the firm's bold- est initiative — an extraordinary collabora- tion with Frank Murphy to produce a sequence of austerely handsome radio cab- inets on a mass scale. In 1929 Gordon Rus- sell Ltd opened a showroom in Wigmore Street and from 1936 to 1939 the art histo- rian Nikolaus Pevsner was its buyer. It would be hard to think of a more absurdly distinguished choice. Up until the outbreak of war Wigmore Street was a mecca both for the firm's own modernist products and Modern Movement design from Europe.

In his charming biography Designer's Trade Gordon Russell drew a veil over his defiencies as a businessman. In 1940 he was forced to resign as managing director of his own firm by the banks. This was hardly a setback. From 1943 to 1947 he was chairman of the Utility Furniture Design Panel and thus able to impose modernism with a Cotswold flavour on the nation. But Polishing Murphy radio cabinets at the Gordon Russell factory in Park Royal in the 1930s did Utility furniture bear out the interwar design consensus that fitness-to-purpose ideas came as second nature to the British? Unfortunately not: after the war, debased modernism and a tide of 'Jaco- bethan' and mock Tudor furnishing proved that as a nation we were both hard to cate- gorise and — apart from the muted, unad- venturous world of the country house style — had an innate poor taste that at times bordered on the gloriously surreal.

And, as these exhibitions reveal, even Gordon Russell's own taste could be unex- pectedly wayward. After two post-war decades in public life as President of the Council of Industrial Design serving on countless committees, Russell started designing furniture again for his own pri- vate pleasure and use. By then he had real doubts about the Modern Movement. He believed that his reintroduction of orna- ment to his late 1970s designs was a revolu- tionary step. But these late-flowering pieces — heavy yew tables and stools lack the refinement of his designs in the 1920s and even bear an odd resemblance to the trade Jacobethan his influence did so much to combat. But he was prophetic. Ornament did return to avant-garde furni- ture but it was employed in the ironic and self-mocking spirit we now call post- modern. In his earnestness and social pur- pose Russell was never to enter that frag- mented, self-referential world. In that sense, despite all his contradictions, he remained a modernist to the end — of a particularly English kind.

Previous page

Previous page