Exhibitions 1

Rene Magritte (Musees Royaux des Beaux Arts, Brussels, till 28 June) Pieter and Jan Brueghel (Koninldijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, till 26 July)

The marvellous in the ordinary

Martin Gayford

You might think Belgium was just a buffer zone, an area where Francophone, Latin culture fades into a northern Euro- pean, Dutch-speaking one. But, surprising- ly, in art especially, it has a character of its own, earthier, less austere than its neigh- bours in either direction, and tending to imaginative phantasmagoria. Both qualities emerge in two current exhibitions of paint- ings done three centuries apart, by Rene Magritte and the brothers Jan and Pieter Brueghel.

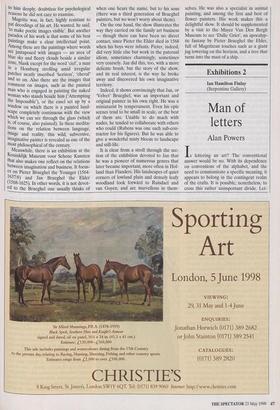

The exhibition celebrating the centenary of the birth of Magritte is packing in the crowds at the Musee des Beaux Arts, so much so that booking a ticket ahead is essential, and entry at weekends virtually impossible. The level of popularity is itself both interesting and paradoxical, given that Reversing the usual expectations: Magritte's 'Golconda, 1953 Magritte thought of Surrealism as a revolu- tionary movement which would bring free- dom to mankind from the suffocating conventionality of bourgeois existence. Yet here are the bourgeoisie of Belgium jammed into the Musee des Beaux Arts to see his work. They love him, just as the hardworking, mercantile types of 16th-cen- tury Flanders loved Brueghel and Bosch.

It is, however, only a superficial paradox, since it is precisely conformist, conventional life that breeds this kind of fantasy. Magritte's unDali-ishly, normal life — living in the Paris suburbs, then in a small apart- ment in Brussels, so devoted to his wife that when she had an affair he called the police — must have fed his imagination. Normali- ty, in a way, was his subject.

Most of the time, what he did was turn it on its head. There is a formula to many Magrittes, as there is to a Wildean epigram — reverse the usual expectation, and so reveal the marvellous in the ordinary. This might apply to scale, so an apple swells to fill an entire room; or to weight, allowing a great, gnarled mass of rock to float in the sky, or to other physical properties, as with the tuba that bursts into flames. Another Magrittean ploy was metamorphosis. Instead of clouds the sky is filled with a woman's torso, a tuba, and a rush chair as in 'Threatening Weather' (1929) — or floating baguettes. Some objects were too emotionally charged for these devices to work: 'Female underwear, for instance, proved very difficult to show in any unex- pected light.'

To an extent, then, Magritte's imagina- tion was predictable — and that is one rea- son why, as time went on, his work became less interesting (the other being that there was less life in the paint). There was unde- niably an element of carry on Magritte about his subversive Surrealist enterprise: it turned into a bit of a business. One has seen almost all the best of this show by the time one is about half-way through (which means it's too big, good shows should cut out the bad bits). The diversion into Renoiresque brushwork in the 1940s was a complete disaster, after which he went back to his earlier style, but in a slick, photoreal- ist fashion.

The early work holds up, on the other hand, very well, and is often painted with a sweet precision that has its own beauty. There is enough on the walls here to demonstrate that Magritte was the most impressive of the fully paid-up Surrealist artists (Miro, who was a more natural painter, never fully joined the movement). As a young man, Magritte clearly pos- sessed genuine imaginative wildness. When he found de Chirico, and hence himself, in his mid-twenties — after a flir- tation with one or two Modernist modes — he seems to be painting jumbled, off the wall, internal imagery. (In this the young Magritte is reminiscent of Gilbert and George, two other subversive revolu- tionaries masquerading as conventional types.) He was fascinated by blobby, amoeba- like shapes and fractured forms which look as if they had been cracked or torn. These eat into predictable, realist images — a woman's head in 'An End to Contempla- tion', a door in 'Portrait of Paul Nouge the random irrational invading the banal. At this point emerge two endlessly reused props: the little spherical bells called `grelots', and the turned-wood objects of his own invention, like elongated chess pieces, called `bilboquets'. Both appealed to him deeply, doubtless for psychological reasons he did not care to examine.

Magritte was, in fact, highly resistant to pat decodings of his art. He wanted, he said, to make poetic images visible'. But another paradox of his work is that some of his best Paintings make a clear intellectual point. Among these are the paintings where words are juxtaposed with images — an area of blue sky and fleecy clouds beside a similar ?one, blank except for the word `cier, a man in a Homburg strolling amid irregular Patches neatly inscribed 'horizon', `cheval' and so on. Also there are the images that comment on images, such as the painted !Ilan who is engaged in painting the naked woman who stands beside him (`Attempting the Impossible'), or the easel set up by a window on which there is a painted land- scape completely continuous with the view Which we can see through the glass (which 15, Of course, also painted). In these medita- tions on the relation between language, !inage and reality, this wild, subversive, imaginative painter is revealed as one of the most philosophical of the century. Meanwhile, there is an exhibition at the kdilinklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten that also makes one reflect on the relations between imagination and business. It focus- es on Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564- 1637/8) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625). In other words, it is not devot- ed to the Brueghel one .usually thinks of when one hears the name, but to his sons (there was a third generation of Brueghel painters, but we won't worry about them).

On the one hand, the show illustrates the way they carried on the family art business — though there can have been no direct contact, since Pieter the Elder died in 1568 when his boys were infants. Pieter, indeed, did very little else but work in the paternal idiom, sometimes charmingly, sometimes very coarsely. Jan did this, too, with a more delicate brush, but the story of the show, and its real interest, is the way he broke away and discovered his own imaginative territory.

Indeed, it shows convincingly that Jan, or `Velvet' Brueghel, was an important and original painter in his own right. He was a miniaturist by temperament. Even his epic scenes tend to be small in scale, or the best of them are. Unable to do much with nudes, he tended to collaborate with others who could (Rubens was one such sub-con- tractor for his figures). But he was able to give a wonderful misty bloom to landscape and still-life.

It is clear from a stroll through the sec- tion of the exhibition devoted to Jan that he was a pioneer of numerous genres that later became important, more often in Hol- land than Flanders. His landscapes of quiet corners of lowland plain and densely leafy woodland look forward to Ruisdael and van Goyen, and are marvellous in them- selves. He was also a specialist in animal painting, and among the first and best of flower painters. His work makes this a delightful show. It should be supplemented by a visit to the Mayer Van Den Bergh Museum to see `DuIle Griet', an apocalyp- tic fantasy by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, full of Magrittean touches such as a giant jug towering on the horizon, and a tree that turns into the mast of a ship.

Previous page

Previous page