Exhibitions 2

Man of letters

Alan Powers

Is lettering an art? The conventional answer would be no. With its dependence on conventions of the alphabet, and the need to communicate a specific meaning, it appears to belong in the contingent realm of the crafts. It is possible, nonetheless, to cross this rather unimportant divide. Let- tering is one of the oldest forms of concep- tual art, where the medium is impersonal and transparent, and everything is con- tained in the message.

This makes it appropriate for the Ser- pentine Gallery, the garden temple of con- ceptualism, to have commissioned a group of works for the surroundings of their refurbished building from the Scottish poet and artist, Ian Hamilton Finlay, his first public commission in London. The work, while well charged with intellectual con- tent, is itself modestly presented, beautiful- ly made and understandable on a variety of levels.

The lawn in front of the gallery has been relandscaped by Colvin and Moggridge, making it more continuous with the sur- rounding park. On the gentle rise leading up to the familiar neo-Georgian former tea house, two groups of four stone bench- es are placed in arcs to either side. On their upper faces (carved by Andrew Whit- tle and Peter Coates) is a series of versions of two from Virgil's Eclogues, first in Latin, then in English in a series of differ- ent translations. It is a ,simple conceit, but one which will draw visitors closely into th tp,xt, an apparently simple statement .0i1C4 the approaching evening, but one which begins to transform the surround- ings in imagination. The extract speaks of cottages with smoking chimneys and the shadow of mountains, transforming the familiar pastoral of the park with a recol- lection of the real country, perhaps even for those who know it of Finlay's remote home in the Pentlands, named by him Lit- tle Sparta.

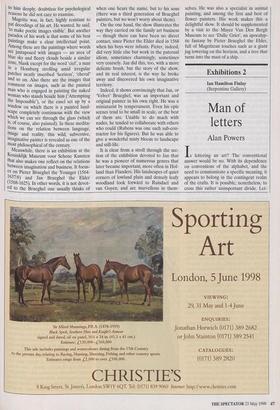

Closer to the road, a horse-chestnut tree carries a tree-plaque, a device often used by Finlay, an oval of slate with another line from the Eclogues, only in Latin this time, translated as 'Home, goats, home, replete, the evening star is coming'. To find this public Latinity in the centre of London, where culture is constantly blown about by the hot air of populism, is quietly reassur- ing — not in a sense of intellectual snob- bery but in the sense that things may be allowed to be difficult and obscure, which will also reward the dedicated inquirer with genuine meaning and insight. This request for culture to be taken seriously is the basis of Finlay's work, and he has at times made a challenge on these grounds to institutions which have been found wanting.

The third element of the commission is a large round piece of slate outside, the new gallery entrance, inscribed in a series of tight circles of capitals, with the Latin and English names of trees and, near the cen- tre, lines from the 18th-century philoso- pher Francis Hutcheson: 'The beauty of trees and their cool shades and their apt- ness to conceal from observation have made groves and woods the usual retreat to those who love solitude especially to the religious, the pensive the melancholy and the amorous.' The work was already in hand last year when Diana, Princess of Wales, who was to have opened it, was killed, and her name at the centre of the roundel makes it perhaps the most apt commemoration she is likely to receive.

While the Serpentine works will remain in place, one hopes, for a century or two, there is only until the end of October to see an equally impressive display of letter- ing at Bliclding Hall, Norfolk, organised in collaboration with the National Trust by Memorials by Artists, a commissioning agency for tombstones and other monu- ments which is celebrating its tenth year. Some 50 examples are beautifully placed in the grounds and the orangery, with some explicatory panels which show how grief can be made more bearable through the medium of art.

People have been at this activity for as long as man has existed, but we may justly claim that in England in the last ten years memorial art has achieved a small flower- ing of lyric intensity which even the epitaph writers of the 17th century and the letter- cutters of the 18th did not surpass. The vast majority of the business of memorialising is in the hands of the monumental masons' trade, which has other priorities, but in the right hands the sharpness of a chisel on a hard material, whether stone or wood, seems to discharge the required emotional content, while the primacy of inscription over image suits our word-based puritan instincts.

The catalogue for The Art of Remembering is published by Carcanet Press at £9.95 (available from FREEPOST MR6474, Manchester M3 9AA, add £1 p&p), and an illustrated booklet from Memorials by Artists at £6 from Snape Priory, Saxmundham, Suf- folk IP17 1SA.

Ian Hamilton Finlay's 'Tree Plaque', 1998

Previous page

Previous page