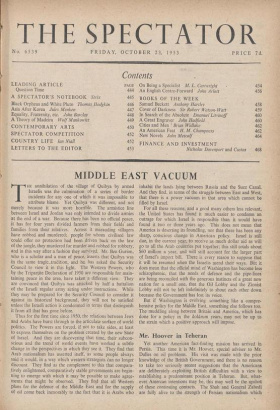

MIDDLE EAST VACUUM T HE annihilation of the village of Quibya

by armed Israelis was the culmination of a series of border incidents for any one of which it was impossible to attribute blame. Yet Quibya was different, and not merely because it was more horrible. The armistice line between Israel and Jordan was only intended to divide armies at the end of a war. Because there has been no official peace, it has for four years divided farmers from their fields and families from their relatives. Across it marauding villagers have robbed and murdered; people for whom civilised law could offer no protection had been driven back on the law of the jungle, they murdered for murder and robbed for robbery, and in this way after a fashion they survived. Mr. Ben Gurion, who is a scholar and a man of peace, asserts that Quibya was in the same tragie_tradition, and he. has asked the Security Council to view it in this light. The Western Powers, who by the Tripartite Declaration of 1950 are responsible for main- taining peace in the area, have taken a different view. They are convinced that Quibya was attacked by half a battalion of the Israeli regular army acting under instructions. While they may be prepared, for the Security Council to consider it against its historical background, they will not be satisfied unless the Israeli action is condemned in terms that distinguish it from all that has gone before.

Thus for the first time since 1950, the relations between Jews and Arabs have burst through to the articulate surface of world politics. The Powers are forced, if ,not to take sides, at least to express themselves on the problem created by the new State of Israel. And they are discovering that time, their subcon- scious and the trend of world events have worked a subtle change in the perspectives in which they see it. They find that Arab nationalism has asserted itself, as some people always said it would, in a way which western-strategists can no longer discount. They find as the complement to this that compara- tively enlightened, comparatively stable governments are begin- ning to emerge with which it may be possible to make agree- ments that might be observed. They find that all Western plans for the defence of the Middle East and for the supply of oil come back inexorably to the fact that it is Arabs who inhabit the lands lying between Russia and the Suez Canal. And they find, in terms of the struggle between East and West, that there is a power vacuum in that area which cannot bo filled by Israel. , For all these reasons, and a good many others less relevant, the United States has found it much easier to condemn an outrage for which Israel is responsible than it would have found it two or three years ago. This does not mean that America is deserting its foundling, nor that there has been any sharp, conscious change in American policy. Israel is still due, in the current year, to receive as much dollar aid as will go to all the Arab countries put together; this still totals about $60 million a year, and will still account for the larger part of Israel's import bill. There is every reason to suppose that it will be resumed when the Israelis mend theft' ways. But it does mean that the official mind of Washington has become less schizophrenic, that the needs of defence and the pipe-lines are being reconciled with the generous instincts of a great new nation for a small one, that the Oil Lobby and the Zionist Lobby will not be left indefinitely to shout each other down because the Government has lost its voice.

But if Washington is evolving something like a compre- hensive policy for the Middle East, something else follows too. The muddling along between Britain and America, which has done for a policy in the doldrum years, may not be up to the strain which a positive approach will impose.

Previous page

Previous page