ei THE CASE AGAINST 1. Standards of living

correctly compared

Douglas Jay One of the most notable examples in recent times of the Goebbels Big Lie is the oft-repeated statement that Britain's standard of living is now lower than most Western European countries including all the Common Market Six except Italy. This has been asserted so often that it is believed by many — even some not infected by our current rather sordid habit of self-denigration for denigration's sake.

But there is no factual or statistical basis for it. More important, it is not true. The Economist excelled itself in this particular form of obfuscation in an article of August 14, 1971, in which it was stated that "Britain's standard of living is as flat as a pancake. The Japanese have now exceeded it" (my italics); and that "whereas in 1960 Britain still had a better standard of living than any Common Market country, today it has fallen behind all except Italy" 'etc.

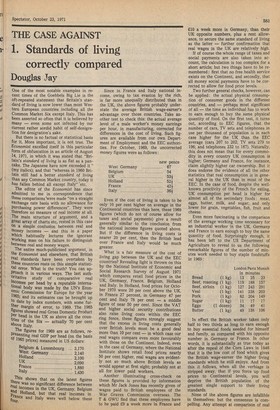

The editor of the Economist has since admitted to me in correspondence that these comparisons 'were made "on a straight exchange rate basis with no allowance for Purchasing power differences". They were therefore no measure of real income at all. The main structure of argument, and a great array of charts etc, rested in this case on a simple confusion between real and money incomes — and this in a paper Which habitually lectures the ignorant working man on his failure to distinguish between real and money wages. The entire much-publicised argument, in the Economist and elsewhere, that British real standards have been overtaken by these countries rests on this simple statistical error. What is the truth? You can approach it in various ways. The last authoritative study of comparative real Incomes per head by a reputable international body was made by the UN's Econcitlic Commission for Europe for the year 1965; and its estimates can be brought up to date by index numbers, with some further margin of error, to 1969. The 1965 figures showed real Gross Domestic Product Per head in the UK as above all the countries of the Six — actually 70 per cent above Italy. The figures for 1969 are as follows, representing real GDP per head (on the basis of 1965 prices) measured in US dollars: This shows that on the latest figures there was no significant difference between reel incomes in the UK, Germany, Belgium and Holland, but that real incomes in France and Italy were well below these four. Since in France and Italy national income, owing to tax evasion by the rich, is far more unequally distributed than in the UK, the above figures probably understate the average British wage-earner's advantage over those countries. Take another test to check this: the actual average level of a male worker's money earnings per hour, in manufacturing, corrected for differences in the cost of living. Such figures are available from our own Department of Employment and the EEC authorities. For October, 1969, the uncorrected money figures were as follows : Even if the cost of living is taken to be only 10 per cent higher on average in the Continental countries than here, these 1969 figures (which do not of course allow for taxes and social payments) give a result generally similar to the conclusion from the national income figures quoted above. But if the difference in living costs is nearer 20 per cent, then the British lead over France and Italy would be much greater.

What is a fair measure of the cost of living gap between the UK and the EEC countries? Revealing light is thrown on this by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research Survey of August 1971 which compares retail food prices in the UK, Germany, France, Belgium, Holland and Italy. In Holland, food prices for October 1970 were 20 per cent above the UK, in France 27 percent, in Germany 47 per cent and Italy 78 per cent — a middle figure of near 50 per cent. Since the VAT and higher social security contributions also raise living costs within the EEC ring fence, these figures strongly suggest that the excess in living costs generally over British levels must be a good deal more than 10 per cent — in which case our real wages compare even more favourably with those on the Continent. Indeed, even in the case of Germany, where the National Institute shows retail food prices nearly 50 per cent higher, real wages are evidently not so much above British levels as would appear at first sight; probably not at all for lower paid workers.

Another illuminating cross-check on these figures is provided by information which Mr Jack Jones has recently given of wages paid to British employees of the War Graves Commission overseas. The T & GWU find that these employees have to be paid £9 a week more in France and £10 a week more in Germany, than their UK opposite numbers, plus a rent allowance, to secure the same standard of living as the latter — further confirmation that real wages in the UK are relatively high.

If of course the whole range of taxes and social payments are also taken into account, the calculation is too complex for a short article; but two things have to be remembered: first that no free health service exists on the Continent, and secondly, that all money social payments have to be corrected to allow for food price levels.

Two further general checks, however, can be applied : the actual physical consumption of consumer goods in the different countries, and — perhaps most significant of all — the time an individual has to work to earn enough to buy the same physical quantity of food. On the first test, it turns out, according to EEC figures, that the number of cars, TV sets and telephones in use per thousand of population is in each case higher for the UK than the EEC• average (cars 207 to 202; TV sets 279 to 196; and telephones 232 to 167). Naturally, this does not mean that for every commodity in every country UK consumption is higher; Germany and France, for instance, claim slightly higher car ownership. But it does endorse the evidence of all the other statistics that real consumption is in general higher in the UK than in most of the EEC. In the case of food, despite the wellknown proclivity of the French for eating, UK consumption per head is higher for almost all of the secondary foods : meat, eggs, butter, milk, and sugar; and only lower for grain, vegetables, fish, fruit and cheese.

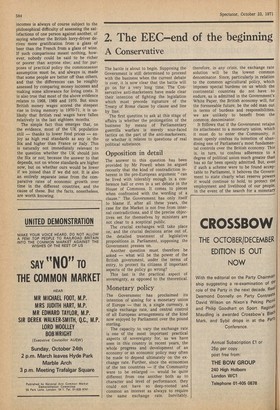

Even more fascinating is the comparison of the average working time necessary for an industrial worker in the UK, Germany and France to earn enough to buy the same quantity of food. Surprisingly enough, it has been left to the US Department of Agriculture to reveal to us the following remarkable figures of the number of minutes work needed to buy staple foodstuffs in 1969: In effect the British worker takes only half to two thirds as long to earn enough to buy essential foods needed for himself and family, as compared with his opposite number in Germany or France. In other words, it is substantially as true today as after the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 that it is the low cost of food which gives the British wage-earner the higher living standards which he still enjoys. And from this it follows, when all the verbiage is stripped away, that if you force up food prices to Continental levels, you will deprive the British population of the greatest single support to their living standards.

None of the above figures are infallible in themselves: but the consensus is compelling. Any attempt at comparison of real incomes is always of course subject to the philosophical difficulty of assessing the satisfactions of one person against another, of saying whether the British lorry-driver derives more gratification from a glass of beer than the French from a glass of wine. If such comparisons meant nothing, however, nobody could be said to be richer or poorer than anyone else; and for purposes of practical policy the commonsense assumption must be, and always is, made that some people are better off than others, and that the differences can be roughly assessed by comparing money incomes and making some allowance for living costs. It is also true that most of the above evidence relates to 1968, 1969 and 1970. But since British money wages scored the steepest rise in living memory in 1970-71, it is unlikely that British real wages have fallen relatively in the last eighteen months.

The simple fact thus emerges that, on the evidence, most of the UK population still — thanks to lower food prices — enjoy as high real standards as any in the Six and higher than France or Italy. This is naturally not immediately relevant to the question whether the UK should join the Six or not; because the answer to that depends, not on whose standards are higher now, but on whether ours would be lower if we joined than if we did not. It is also an entirely separate issue from the comparative rates of economic growth over time in the different countries, and the cause of these. But the facts, nonetheless, are worth knowing.

Previous page

Previous page