Scratch one Suzuki

Murray Sayle

Tokyo All the angels in heaven weep, we know, when a single sparrow falls. But Japanese prime ministers? Inscrutable as Buddhas, these men with unmemorable names — Tanaka, Miki, Fukuda, Ohira — :1,eal in, bask a season in the sun, and bow silently out, unremarked and unregretted. Last week another name not exactly to con- lure with, Zenko Suzuki( not even related to the small, economical motor-cars), an- nounced that he would not contest the Ijorthcoming election for the presidency of 11:13an's perpetual ruling party, the Liberal ernocrats, thus in effect resigning as undistinguished Prime Minister after a short and undistinguished term in office. I Did Suzuki fall, or was he pushed, and i„°es it matter? We might begin by observ- cig that the soon-to-be-ex-Prime Minister hid not exactly strain himself in office, and enjoys excellent health. So, at first d"Ilce, does the Japanese economy, thestroYer of governments in other parts of ore world. Business is brisk, largely because duM the insatiable demand for Japanese pro- la Europe and the US, with the result abat unemployment is only 2.5 per cent, „21.1t quarter of that enjoyed by Japan's j'asloMers. Inflation is 3 per cent, and the

.Pallese banks are awash with cash.

betne economic outlook may not, in fact, Mt quite as rosy as these figures suggest, theh, for example, about two or three times for afficial percentage of people looking the a job and not finding one. But, if male, 41.11' are back working on the family farm, Few if female at home watching television. faiapanese have lost their rural roots, take_ InllY expectations are not such that it S0 4 two salaries to satisfy them.

1114 none of the social scars of unemploy- .` are yet apparent in Japan — there are

i and nod

"ng industrial towns infested with idle uliaminatinous youth, no school-leavers ly _"`e to find any kind of job, and certain- n

tetr ° jobless immigrants whose line of eat to the farm is cut off by the width of nee — ‘-)11 a rough test, every Japanese ,,u nees a job has one.

I■14 has certainly not cut a Pol

the wocnic, or even Thatcherian figure on ate grateful. stage, for which some Japanese °kr Last year, for instance, he told iiged Americans (through an interpreter defers speaks no English) that Japan's house Posture was that of a `clever eck when he meant to say 'wise oth°T.er8'. Scratch one interpreter. On the eke. Of 'land, Suzuki has managed to wriggle the affair of the school textbooks, bhr ati Y tidied up by Japanese education reetcrats to make Japan's horrible track hi in Asia sound prettier, without ac-

tually bending to the storm of protest from Japan's neighbours. Japan's public finances are in an awesome mess, but they already were when Suzuki took office two years and three months ago, promising to balance the budget without raising taxes by the mystical year 1984. In fact, he has surprised no one by running up an Argentinian-sized deficit for the current year alone of £13.5 billion ($22.9 billion) which will go to swell Japan's gigantic public debt. 13 ut the money is owed by Japanese to other Japanese, mostly banks, and no one is sure why this form of finance cannot go on indefinitely. If there is widespread discontent in Japan, it comes from a feeling that things are drif- ting, and that something nasty, as yet unspecified, is about to happen. And, quite possibly, it will. . Japanese often get attacks of free- floating anxiety (as Sigmund used to call it), and Suzuki added some more at a press conference he called last month to explain the latest exercise in creative book-keeping devised by his bureaucrats to finance the deficit, a scheme involving relabelling the public works budget 'investment' and not counting it, and borrowing from govern- ment contingency funds to pay current debts. Basically, the Japanese business world is calling for Keynesian pump- priming, but there is no money to pay for it without raising taxes, which will further depress domestic spending, already slug- gish, or laying hands on the £300 billion which thrifty Japanese have put by in the post office and other tax-free savings, which the voters would never stand for. Ad- mitting that his vow to balance the books by 1984 could not be kept, Suzuki pro- claimed a 'state of fiscal emergency', an original way of describing a situation which has been normal in Japan for the past decade.

The phrase, however, made headlines on financial pages all over the world, alerting

those still in yen to get out. The Japanese currency fell to its lowest rate against the dollar, and even the pound, for five years, which in turn made even bigger headlines in Japan. Normally a cheap yen is good news, presaging another flood of Japanese ex- ports, but there are now so many `gentlemen's agreements' and 'voluntary restraints' in force that Japanese manufac- turers dare not take advantage of the cur- rent weakness of the yen, while imported food, fuel and raw materials (as well as Scotch whisky and woolly sweaters) will all go up. Businessmen sank deeper into their freischwimmende Angst but this was neither the proximate nor effective cause of Suzuki's fall.

For this (and the real story) we must turn to a series of meetings which have been go- ing on for the past three weeks, and still continue. Former prime minister Kakeui Tanaka (64) accompanied by the dozen or so reporters who maintain constant, round- the-clock watch outside his house, has been calling on former prime minister Nobosuke Kishi (81) at the latter's home on the slopes of Mount Fuji, where another gaggle of Japanese newsmen stand sleepless vigil. Why so much interest in has-beens? Because this pair, not previously on good terms, dominate Japanese politics.

Kishi, the Albert Speer of Japan, and no stranger to these pages, was the Minister for Munitions during the second world war, and spent the years 1946-1949 in prison while painstaking Americans wrote him a part in a grandiose conspiracy theory stret- ching back to Japan's occupation of Man- churia in the 1930s. The trial of Kishi and his colleagues as war criminals was aban- doned in 1949, as the cold war drew nigh, and Kishi went on to become prime minister between 1957 and 1960. He was forced out of office by anti-American riots in that year, but not before he had made the riskiest decision of post-war Japanese politics, the secret agreement permitting the US forces to bring tactical nuclear weapons (but not the strategic, publicly acknowledged kind) into Japan, an agreement which, as far as anyone knows, still stands. Kishi passed the leadership of his parliamentary faction to Takeo Fukuda, another former prime minister, and Kishi's son-in-law, Shintaro Abe, is today Fukuda's and thus godfather Kishi's heir-apparent.

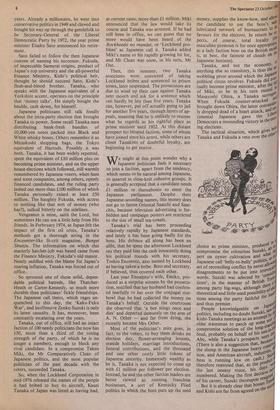

Tanaka is not exactly our bumbling, eager-to-please Suzuki type, either. Son of a bankrupt horse-dealer, and beneficiary of no more than six years' elementary school- ing (if that) the shrewd and tough Tanaka was invalided out of the army in China in 1940 and built up a big black market building business in Tokyo during the war years. Already a millionaire, he went into conservative politics in 1949 and clawed and bought his way up through the gentlefolk to be Secretary-General of the Liberal Democratic Party by 1972, the year prime minister Eisaku Sato announced his retire- ment.

Sato failed to follow the then Japanese custom of naming his successor. Fukuda, of impeccable Samurai origins, product of Japan's top university and the all-powerful Finance Ministry, Kishi's political heir, thought he should succeed Sato, Kishi's flesh-and-blood brother. Tanaka, who speaks with the Japanese equivalent of a Yorkshire accent, operates on the principle that 'money talks'. He simply bought the bauble, cash down, for himself.

Japanese politicians still talk fondly about the intra-party election that brought Tanaka to power. Some recall Tanaka men distributing bank-fresh bundles of 10,000-yen notes packed into Black and White whisky boxes. Others remember it as Mitsukoshi shopping bags, the Tokyo equivalent of Harrods. Possibly it was both. Tanaka, it has been widely reported, spent the equivalent of £10 million plus on becoming prime minister, and on the upper house elections which followed, still warmly remembered by Japanese voters, when ham and scent companies, among others, openly financed candidates, and the ruling party lashed out more than £100 million of which Tanaka personally raised at least £50 million. The haughty Fukuda, with access to nothing like that sort of money (who has?), sulked bitterly on the sidelines.

Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord, but sometimes He can use a little help from His friends. In Ferbruary 1974, as Japan felt the impact of the first oil crisis, Tanaka's methods got a thorough airing in the Encounter-like lit-crit magazine, Bungei Shunju. The information on which this masterly hatchet-job was based came from the Finance Ministry, Fukuda's old manor. Neatly saddled with the blame for Japan's roaring inflation, Tanaka was forced out of office.

So sprouted one of those solid, depen- dable political hatreds, like Thatcher- Heath or Carter-Kennedy, so much more durable than politicians' fickle friendships. The Japanese call theirs, which rages un- quenched to this day, the `Kaku-Fuku War', and inoffensive Zenko Suzuki is only its latest casualty. It has, moreover, been constantly escalating over the years.

Tanaka, out of office, still had an intact faction of 100 needy politicians (he now has 130, more than a third of the voting strength of the party, of which he is no longer a member), enough to block any rival candidate. In a compromise Takeo Miki, the Mr Comparatively Clean of Japanese politics, and the most popular politician of the past decade with the voters, succeeded Tanaka.

So, when the Lockheed Corporation in mid-1976 released the names of the people it had bribed to buy its aircraft, Kauei Tanaka of Japan was listed as having had,

at current rates, more than £1 million. Miki announced that the law would take its course and Tanaka was arrested. If he had still been in office, we can guess that no more would have been heard of the Rockheedo no mondai, or `Lockheed-pro- blem' as Japanese call it. Tanaka added Miki's name to his rapidly growing hit list, and Mr Clean was soon, in his turn, Mr Out.

Then, this summer, two Tanaka associates were convicted of taking Lockheed bribes and sentenced to prison terms, later suspended. The prosecutors are due to wind up their case against Tanaka next month and ask for a sentence which can hardly be less than five years. Tanaka can, however, put off actually going to jail for another five years, through layers of ap- peals, meaning that he is unlikely to resume what he regards as his rightful place as prime minister until 1922. At this distant prospect his bloated faction, some of whom have joined since his arrest, while others are closet Tanakists of doubtful loyalty, are beginning to get restive.

We might at this point wonder why a apanese politician feels it necessary to join a faction, apart from the tendency, which seems to be natural among Japanese, to quarrel in close-knit cohesive groups. It is generally accepted that a candidate needs £1 million or thereabouts to enter the Japanese parliament. Despite their Japanese-sounding names, this money does not go to fatten Oriental Saatchi and Saat- chis, because television advertising is for- bidden and campaign posters are restricted to the size of small tea-towels.

Tanaka's trial has been proceeding relatively rapidly by Japanese standards, and lately it has been going badly for the boss. His defence all along has been an alibi, that he spent the afternoon Lockheed say they paid him the cash innocently doing his political rounds with his secretary, Toshio Enomoto, also named by Lockheed as having taken a bribe. Boss and secretary, if believed, thus covered each other.

Last year Enonioto's wife, Emiko, pro- duced as a surprise witness by the prosecu- tion, testified that her husband had confess- ed tearfully to her over the conjugal rice- bowl that he had collected the money on Tanaka's behalf. Outside the courtroom she observed that 'a bee stings once and dies' and departed demurely on the arm of A. N. Other — and far from dying, she recently became Mrs Other.

Most of the politician's mite goes, in fact, to the voters, to buy them drinks on election day, flower-arranging lessons, seaside holidays, marriage introductions, funeral contributions, and the thousand and one other costly little tokens of Japanese sincerity. Immensely wealthy as he is, Tanaka is not expected to come up with £1 million per follower per election. Instead, he and the other faction leaders are better viewed as running franchise businesses, a sort of Kentucky Flied politics in which the boss puts up the seed

The Spectator 23 October l982 money, supplies the know-how, and alloy the candidate to use the boss's weg: lubricated network of bureaucrats to 0° favours for the electors. In return he t pects, of course, total loyalty (11' masculine pronoun is for once appropria,teei as a lady faction boss on the British mod is, at best, the faintest of clouds on t"'

Japanese horizon). of

Tanaka, and not the economy, anything else so transitory, is thus the wobbling pivot around which the Japanese political circus revolves. Fukuda did eV iefil' tually become prime minister, after the 0„" of Miki, to be in his turn ousted °.1. Masayoshi Ohira, a Tanaka surrogOd When Fukuda counter-attacked 31/1 brought down Ohira, the latter convenielln, ly dropped dead of a heart attack, and„seraj timental Japanese gave the Lino, Democrats a resounding victory in the e°' ing elections. battl The tactical situation, which gives „.f.s Tanaka and Fukuda a veto over the et"" choice as prime minister, produced ase compromise the colourless Suzuki, Ility pert on oyster cultivation and vvilanrt ty Japanese call 'belly-to-belly' politics, vo art of reconciling conflict by never all° gig disagreements to be put into irrevtjir words. Suzuki was selected by `C°r" tions', in the manner of British T01:5 among party big-wigs, although thel4et theoretical and little-used possibilitY "de tions among the party faithful for lea and People premier. knowledgeable on jaPalli thus politics, including no doubt Suzuki, st'' Kishi-Tanaka meetings as an attempt 'Yri 6 elder statesman to patch up soine s°_„di compromise solution of the long- lay probably on behalf of his son-in-do Abe, while Tanaka's prospects weredse (There is also a suggestion that, beca",to, the slump in the Japanese heavY con tion, and American aircraft, industr;110 boss is running low on cash.) ct therefore reasoned that, as the Prc'tiot the last uneasy truce, his daYs too numbered. Making the first deciaiveej. of his career, Suzuki thereupon resigned

But it is already clear that bosses ,r and Kishi are far from agreed on the su sion. Instead of smooth 'consultations' the hypothetical party primary has now actual- ly been announced for the end of November, and four candidates have taken the field.

Yasuhiro Nakasone has his own faction, is suitably right-wing, and has been waiting off-stage a long time. But the candidates (two on the present interpretation of the rules) still have to survive confirmation by the parliamentary party. Nakasone is close both to Tanaka and Yoshio Kodama, gangster boss and another Lockheed defen- dant, and he is also Fukuda's detested rival in their joint constituency. If he wins, Tanaka rule is confirmed.

Shingaro Abe is Fukuda's heir and Kishi's son-in-law. If he wins, Tanaka's power has been broken. This would surprise Tally observers, including this one. Toshio Nornoto, a shipping tycoon, has an ex- cellent chance in the primary, having, it is said paid the £7 membership fee for some 4°°,000 of the one million membership of the Liberal Democratic Party. He also has some public following as a practical ,..°11slness type. His chances of getting con- tinued are not good, because his rivals can- not raise this kind of money and fear the Precedent. Ichiro Nakagawa has his own faction, but not as well funded as the others tkomoto, for instance, is closely connected with Ryoichi Sasakawa, Japan's wealthiest gambling boss). He is a former member of the seiran-kai, the 'blue storm society', a collection of junior hawks who used to ad- Icocate massive Japanese rearmament, acked, along with Abe, by the Fukuda fac- v.,'c'n and thus, if he wins, a further sign of Tanaka decline. l. It is difficult, given the double hurdle they must cross, to see how any of these candidates can attract well-informed Punters. The party leaders seem to agree, and have called a week's moratorium on :111, Paigning for more 'consultations', 1°1, if successful, could only lead to a "tilother uneasy truce and the nonentity-of- the-month named once again as premier. t,, the alternative is an open split in the par- .,and possibly two conservative parties. ,.111s would not, however, be the end of the .w.orid, or even rule by much the same peo- f2e, as there are several smaller parties will- s'Ig, and eager to join the larger surviving 441111cinter. But the process is bound to be long

li messy. The total paralysis of Japanese po ' .

11cs, in place of the betrayal and

co of the Tanaka years, may

1711 turn out be be exactly the something tasty so many Japanese think is hanging in ili! air, waiting to happen — just at the a,'nent, too, when the wolves are howling '1aPan's door. those is Possible to see these manoeuvrings as and heedless of men hungry for power and money iy7eedless of the national interest. Equal- • " can discern the Japanese tendency to give , . . th. Priority to the organisation rather than 0`.:. Job in hand, which is presumably the p„,41(nd iloting of SS Japan, as Fukuda liked liked to describe his vocation.akeo

More generously, we can say that here is a society where a clear majority would like to practise more open and democratic politics but are uncertain how to combine them with Japanese tradition. Japanese history abounds with retired emperors and shoguns ruling from behind the scenes, and Tanaka can be viewed as just another one, his power fortunately curbed by his legal problems. Arriving at a form of government which would avoid the disasters of the past (of the kind, for instance, edited out of the school textbooks) is indeed far more important to Japan's future than the unemployment rate or the government's debts. It is even possi- ble that, in the manner of his going, harmless Zenko Suzuki, both wise hedgehog and clever mouse, has done his country some good.

Previous page

Previous page