AN UNFULFILLED ECCENTRIC

Martin Vander Weyer talks to

Lord Palumbo, a tycoon with much to be defensive about

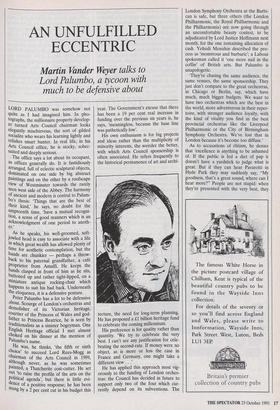

LORD PALUMBO was somehow not quite as I had imagined him. In pho- tographs, the millionaire property develop- er turned As Council chairman looks elegantly mischievous, the sort of gilded socialite who wears his learning lightly and relishes smart banter. In real life, in his Arts Council office, he is stocky, sober- suited and deeply serious. The office says a lot about its occupant, as offices generally do. It is fastidiously arranged, full of eclectic sculptural objects, dominated on one side by big abstract paintings and on the other by a roofscape view of Westminster towards the rarely seen west side of the Abbey. The harmony of ancient and modern is central to Palum- bo's thesis: 'Things that are the best of their kind,' he says, no doubt for the umpteenth time, 'have a mutual recogni- tion, a sense of good manners which is an acknowledgment of one period to anoth- er.'

, As he speaks, his well-groomed, soft- jowled head is easy to associate with a life In which great wealth has allowed plenty of time for aesthetic contemplation, but the hands are chunkier — perhaps a throw- back to his paternal grandfather, a cafe proprietor from Amalfi. He keeps the hands clasped in front of him as he sits, buttoned up and rather tight-lipped, on a miniature antique rocking-chair which happens to suit his bad back. Underneath the eloquence, it is a defensive posture. Peter Palumbo has a lot to be defensive about. Scourge of London's orchestras and demolisher of its Victorian heritage, courtier of the Princess of Wales and god- father to Princess Beatrice, he is seen by traditionalists as a sinister bogeyman. One English Heritage official I met almost Choked on his dinner at the mention of Palumbo's name.

He was, he thinks, 'the fifth or sixth choice' to succeed Lord Rees-Mogg as chairman of the Arts Council in 1989, although never, as he was sometimes Painted, a Thatcherite cost-cutter. He set out to raise the profile of the arts on the political agenda', but there is little evi- dence of a positive response; he has been stung by a 2 per cent cut in his budget this year. The Government's excuse that there has been a 19 per cent real increase in funding over the previous six years is, he says, 'meaningless, because the base line was pathetically low'. His own enthusiasm is for big projects and ideas rather than the multiplicity of minority interests, the weirder the better, with which Arts Council sponsorship is often associated. He refers frequently to the historical permanence of art and archi- tecture, the need for long-term planning. He has proposed a £1 billion heritage fund to celebrate the coming millennium.

His preference is for quality rather than quantity. 'We try to celebrate the very best. I can't see any justification for cele- brating the second-rate. If money were no object, as is more or less the case in France and Germany, one might take a different view . .

He has applied this approach most vig- orously to the funding of London orches- tras: the Council has decided in future to support only two of the four which cur- rently depend on its subventions. The London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbi- can is safe, but three others (the London Philharmonic, the Royal Philharmonic and the Philharmonia) are now going through an uncomfortable beauty contest, to be adjudicated by Lord Justice Hoffmann next month, for the one remaining allocation of cash. Yehudi Menuhin described the pro- cess as 'monstrous and barbaric; a Labour spokesman called it 'one more nail in the coffin' of British arts. But Palumbo is unapologetic.

`They're chasing the same audience, the same venues, the same sponsorship. They just don't compare to the great orchestras, in Chicago or Berlin, say, which have much, much bigger budgets. We want to have two orchestras which are the best in the world, more adventurous in their reper- toire, with stronger audience loyalty, with the kind of vitality you find in the best provincial orchestras like the Liverpool Philharmonic or the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. We've lost that in London because it's become too diffuse.'

As to accusations of elitism, he denies that 'excellence is anything to be ashamed of. If the public is fed a diet of pap it doesn't have a yardstick to judge what is great. But if they can hear Pavarotti in Hyde Park they may suddenly say, "My goodness, that's a great sound, where can I hear more?" People are not stupid: when they're presented with the very best, they sense it; there's something about great art that does that.'

He is also a fervent believer in innova- tion. 'The nature of experiment is that it is going to fail most of the time. But unless you try it, you won't pick up the 1 or 2 per cent of new ideas that are really going to shake the world. History is littered with geniuses who were unsupported for most of their lives.'

He clearly sees himself as a supporter of spurned genius, and is dismayed by the lack of British appetite for new ideas, most especially in architecture, which he has brought within the Arts Council ambit for the first time. He laments our distaste for the kind of grand projects favoured by the French, which he says are regarded here as `vulgar and an4viste'.

This last comment perhaps carries a more personal note of defensiveness. Although his Arts Council job places him at the heart of the establishment, he is still in some ways an outsider. And British architectural prejudices have so far left his first career, as a property developer, curi- ously unfulfilled: having inherited a £60 million commercial property empire, Palumbo has spent his entire working life from the age of 22 (he is now 58) trying to bring one monumental building project to fruition.

It has cost him several of his millions but, so far, not a single bucket of concrete has been poured. The site is the `Mappin & Webb' triangle opposite the Mansion House in the City of London, on which Palumbo bought the first of 350 separate leaseholds in 1958.

His choice of architect was the German modernist Mies van der Rohe, whose work he had admired since his schooldays and whom he later knew and revered. Van der Rohe's 'Farnsworth' house in Illinois, a transparent box of steel and glass in a woodland setting, forms part of Palumbo's extraordinary architectural collection not of drawings or models but of actual buildings; he also owns a Frank Lloyd Wright house in Pennsylvania and a pair of houses by Le Corbusier in Neuilly-sur- Seine.

Van der Reihe designed a stark skyscraper and an open piazza to replace the jumble of ornate Victoriana on the Mansion House corner. Traditionalists hated the scheme, which the Prince of Wales called 'yet another giant glass stump, better suited to downtown Chica- go'. Permission was first denied by the City authorities in 1969; their decision was finally confirmed after a momentous pub- lic enquiry in 1984.

`It was a very, very big disappointment, no hiding that,' Palumbo says. 'It would have been a great boon to the architec- tural patrimony of the City to have a build- ing by Mies. But you can't be bitter about it, you have to get on with something else.'

His next choice of architect was James Stirling, who counted van der Rohe among his influences. Again Palumbo met opposi- tion: Gavin Stamp, from the pulpit of The Spectator, denounced Palumbo's modernist arguments as facile and the new scheme as a 'vain folly'. This one, the Prince of Wales opined, looks like 'a 1930s wireless set'. (Now that Palumbo is regularly seen with his Lebanese wife on the Princess of Wales's social circuit, his oblique disdain for the Prince's architectural taste carries a new frisson. Palumbo refused to be drawn on the contrast of modernism and fogeyism reflected in the rival Wales courts — 'Let's leave him out of it.') Palumbo got planning permission for the Stirling design at last in 1991, after appeal- ing to the House of Lords. Demolition starts next year and the building should be finished, 38 years after the first leaseholds were bought, in 1996. Did he, I wondered, still see the development as a business propo- sition after all this time and cost, or has it become a pure architectural statement, perhaps even a monument to himself?

Property development gives you an opportunity to express your own vision; that's what attracted me about the busi- ness. If you can build a' great building beautiful, functional, well-constructed — it will be a sound investment. A lot of what goes up in the City is absolutely third-rate, because of planning restrictions and pres- sures of time, money, shareholders. I've tried to achieve architecture of real dis- tinction. It will be part of Jim Stirling's legacy, it's important for his memory.' `Architecture is the most intrusive art form,' Palumbo says. `You can't escape it, it's very emotive. The climate is hostile in this country. It's a problem of education. What we lack is a recognition that there's room for everybody. All architectural styles have something to offer if they're true to their own code. Excellence should be the only yardstick.'

Whether you share Palumbo's taste or not — he even likes the unforgivable new Lloyd's building — you have to acknowl- edge his solitary single-mindedness. Defending his tastes in public is, I suspect, tiresome to him: of all his projects, the one which says most about him is his plan to build an underground house on a rock in the Hebrides. Beneath that subfusc suave- ness, there is a character endearing to some, dangerous to others: a genuine English eccentric.

Previous page

Previous page