FINE ARTS SPECIAL Exhibitions 1

Japan and Europa 1543-1929 (Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, till 12 December)

Big is beautiful

Celina Fox admires European skill and panache in presenting large-scale exhibitions One cultural form that has become vir- tually extinct in Britain in recent years is the large-scale, multi-disciplinary exhibi- tion. The 'blockbuster' seemingly fell victim to its own insatiable appetite for ever more glittering prizes, gargantuan box-office receipts and merchandising bonanzas. The truth is that these spectacles rarely broke even. Besides insurance and transport costs, their elaborate design and installa- tion, partly to suggest historical Context, Partly to meet the increasingly stringent environmental conditions placed on loans, Were hugely expensive. Such factors have not deterred our Euro- pean neighbours. The Council of Europe, the French Reunion des Musees Nationaux and German Lander are still prepared to spend money on ambitious cultural shows. And they appear to be able to stage them Without the trivialising razzmatazz that usu- ally accompanied and sometimes smoth- ered Anglo-American versions of the genre. Admittedly, their governments have until now freed them from the necessity of crude commercialisation. But perhaps we also lack their broad historical perspective and willingness to embrace big ideas. Possi- NY audiences here expect to be diverted rather than educated. Certainly the emi- nences who control the largest exhibition spaces in London have amply demonstrat- ed they are only interested in 'fine' art nar- biwlY i interpreted, with an overwhelming as n favour of the Impressionist-Con- temporary axis. And it is undeniably easier to hang pictures on walls according to Some aesthetic version of divine right than to think through the problems of repre- senting complex historical phenomena with serious scholarship and visual imagination. These thoughts crossed my mind last week in Berlin as I made my way through the still desolate wasteland south of Pots- darner Platz to the Martin-Gropius-Bau. Recently vacated by American Art in the 20th Century, now at the Royal Academy, this massive pile has housed over recent years the temporary exhibitions staged by the enterprising Berliner Festspiele. Some of its shows — notably Prussia in 1981 and Berlin, Berlin in 1987 — have been pioneer- ing attempts to present weighty themes in German history with theatrical panache. Another series examines the relationship between Europe and other cultures: the New World in 1982, the Orient in 1989 and, this year, Japan from 1543 to (tactful- ly) 1929. Think of every Japanese show you have ever seen in London — from The Great Japan Exhibition held at the Royal Academy in 1981-82 to Japan and Britain, an Aesthetic Dialogue at the Barbican ten years later — and you will have an idea of some of the themes tackled in Berlin.

The disadvantage is obvious: terminal exhaustion by the time you've crawled round 20 galleries containing over 600 exhibits, with a catalogue and a supplemen- tary volume of essays to match. The advan- tage is an expanse of cultural horizon which does not isolate art from the rest of society and brings together products of civilisations long submerged under layers of 'progress', creating a richness of texture as the conventions of Europe and Japan are both absorbed and transmogrified. Berlin is well placed to unite works from the West (the British Museum and V & A as usual have been extremely generous in their loans) and from the East, from Cra- cow and St Petersburg as well as the Pacific rim from San Francisco to Kobe.

The vast centre courtyard of the Martin- Gropius-Bau is divided in the manner of a Japanese house with a lavish array of nan- ban screens, the fruits of early contact with the Portuguese. They depict the bearded foreigners in tall hats and balloon breeches coming ashore from ships accompanied by an impressive assortment of goods, pets, servants and black-gowned Jesuits, the scenes unified by conventionalised gold clouds which eliminate the need for per- spective. But the most extraordinary gloss on these works is a screen from the Muse- um de America in Madrid, dating from the second half of the 17th century. It shows the palace of the viceroy in Mexico City, with a procession of dignitaries passing before distinctly Latin-American buildings and native Americans squatting unper- turbedly in the foreground, but with a band of embossed gold clouds dancing across the middle of each panel in a zany mistransla- tion of the Japanese style.

Conversely, printed maps and images of Europe are taken by the Japanese and adapted for views of the world and prospects of distant cities and landscapes as dreamily fanciful as the backdrops to early Renaissance paintings. Books are printed on the press brought by the Jesuits and, more ominously, guns and instruction man- uals on their use are produced while James I and the shogun exchange suits of armour, courtesy of the East India Company.

The exhibition must present the most splendid display of Japanese export lacquer ever assembled, ranging from 17th-century nests of barrel-lidded trunks and cabinets- on-stands from the royal houses of Den- mark and the Netherlands to a magnificent Weisweiler secretaire from the Hermitage. The porcelain is equally sumptuous, spirit- ed out of noble Kunstkammem from Dres- den to Oxford, its choice again confirming the inspiration Japan provided for the 18th-century European decorative arts.

These grand luxe goods were under- pinned by the gradual introduction of Western learning to Japan and the seeping out of information about Japan to Europe. The exhibition is exceptional in tracing the manifestations of this contact through sci- entific instruments and illustrated treatises produced in Japan. The scholar-physicians ,v,-ho served with the Dutch East India Company made exemplary use of their position, transmitting knowledge in both directions. In 1695, Andreas Cleyer pub- lished the first Flora Japonica in Berlin. Engelbert Kaempfer's History of Japan was first published in English translation in London in 1727, for his manuscripts had been acquired by Sir Hans Sloane; they are consequently lent to the exhibition by the British Library.

In the early 19th century, Philipp Franz von Siebold not only taught Japanese stu- dents Western medicine but commissioned Japanese artists, notably Kawahara Keiga, to illustrate his studies and travels. He also acquired 12 water-colours by Hokusai, and a selection of these, now in the Rijksmuse- urn's ethnology collection in Leiden, is among the highlights of the exhibition. In one, a merchant and his wife watch their assistant totting up the accounts by abacus, a cat with a pink ribbon round its neck sleeping peacefully beside them. In anoth- er, a fisherman sits on the seashore mend- ing his nets, his wife dutifully helping him, while their unruly band of infants swarm, swing and somersault over an enormous anchor marooned on its side on the sand.

Alexander von Humboldt had met von Siebold in Berlin in 1834 and when news came 19 years later of Commodore Perry's momentous voyage and the imminent opening of Japanese ports to Western ships, he wrote a letter to him (included in the show) prophesying that Japan, despite being then a backward feudal state, would become celebrated as a great economic power. The second half of the exhibition traces the steps by which this was achieved, at least in part through cultural appropria- tion on a massive scale.

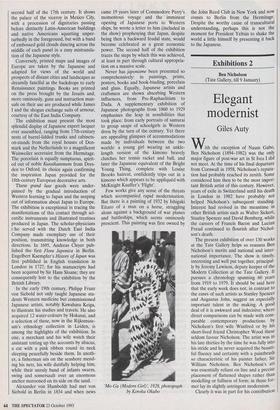

Never has japonisme been presented so comprehensively: in paintings, prints, posters, books and book-binding, porcelain and glass. Equally, Japanese artists and craftsmen are shown absorbing Western influences, from Pre-Raphaelitism to Dada. A supplementary exhibition of Japanese photographs from 1860 to 1929 emphasises the leap in sensibilities that took place: from early portraits of samurai to group snaps of schoolgirls in Western dress by the turn of the century. Yet there are appealing glimpses of accommodations made by individuals between the two worlds: a young girl wearing an ankle- length version of the kimono bravely clutches her tennis racket and ball, and later the Japanese equivalent of the Bright Young Thing, complete with Louise Brooks haircut, confidently trips out in a kimono which appears to be appliquéd with McKnight Kauffer's 'Flight'.

Few works give any sense of the threats which accompanied rapid modernisation. But there is a painting of 1932 by Ishigaki Eitaro of a man on a horse, struggling alone against a background of war planes and battleships, which seems ominously prescient. This painting was first owned by `Mo-Ga (Modern Girl); 1928, photograph by Koroku Okubo the John Reed Club in New York and now comes to Berlin from the Hermitage. Despite the worthy cause of transcultural understanding, perhaps this is not the moment for President Yeltsin to shake the world a little himself by presenting it back to the Japanese.

Previous page

Previous page