Art and business

A practical Utopia

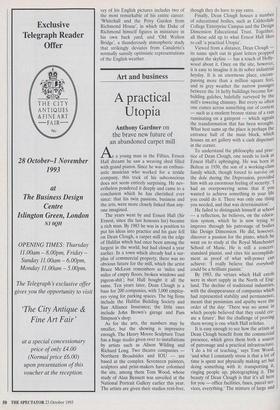

Anthony Gardner on the brave new future of an abandoned carpet mill Aa young man in the Fifties, Ernest Hall dreamt he saw a weaving shed filled with grand pianos. Since he was an enthusi- astic musician who worked for a textile company, this trick of his subconscious does not seem entirely surprising. He nev- ertheless pondered it deeply and came to a conclusion which he has cherished ever since: that his twin passions, business and the arts, were more closely linked than any- one imagined.

The years went by and Ernest Hall (Sir Ernest, since the last honours list) became a rich man. By 1983 he was in a position to put his ideas into practice and his gaze fell on Dean Clough, a carpet mill on the edge of Halifax which had once been among the largest in the world, but had closed a year earlier. In a town which already had a sur- plus of commercial property, there was no obvious future for the mill, which the artist Bruce McLean remembers as 'miles and miles of empty floors, broken windows and pigeon-shit'; but Hall bought it all the same. Ten years later, Dean Clough is a base for 200 companies, with 3,000 employ- ees vying for parking spaces. The big firms include the Halifax Building Society and Sun Alliance Insurance; the little ones include John Brown's garage and Pam Simpson's shop.

As for the arts, the numbers may be smaller, but the showing is impressive enough. The Henry Moore Sculpture Trust has a huge studio given over to installations by artists such as Alison Wilding and Richard Long. Two theatre companies Northern Broadsides and IOU — are based at the complex. Seventeen painters, sculptors and print-makers have colonised the site, among them Tom Wood, whose study of Alan Bennett was unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery earlier this year. The artists are given their studios rent-free, though they do have to pay rates. Finally, Dean Clough houses a number of educational bodies, such as Calderdale College Enterprise Campus and the Design Dimension Educational Trust. Together, all these add up to what Ernest Hall likes to call 'a practical Utopia'.

Viewed from a distance, Dean Clough its name spelt out in giant letters propped against the skyline — has a touch of Holly- wood about it. Once on the site, however, it is easy to imagine it in its sober industrial heyday. It is an enormous place, encom- passing more than a million square feet, and in grey weather the narrow passages between the 16 hefty buildings become for- bidding gulches, balefully surveyed by the mill's towering chimney. But every so often one comes across something out of context — such as a modern bronze statue of a ram ruminating on a gatepost — which signals the transformation that has been wrought. What best sums up the place is perhaps the entrance hall of the main block, which houses an art gallery with a cash dispenser in the corner.

To understand the philosophy and prac- tice of Dean Clough, one needs to look at Ernest Hall's upbringing. He was born in Bolton in 1930, the son of a working-class family which, though forced to survive on the dole during the Depression, provided him with an enormous feeling of security: 'I had an overpowering sense that if you wanted to achieve something in your life you could do it. There was only one thing you needed, and that was determination'.

He failed to distinguish himself at school — a reflection, he believes, on the educa- tion system, which he is now trying to improve through his patronage of bodies like Design Dimension. He did, however, discover a passion for the piano, which he went on to study at the Royal Manchester School of Music. He is still a concert- standard pianist, and cites his accomplish- ment as proof of what will-power can achieve: really believe that everybody could be a brilliant pianist.' By 1983, the virtues which Hall extols were in short supply in the North of Eng- land. The decline of traditional industries, with the disappearance of companies which had represented stability and permanence, meant that pessimism and apathy were the order of the day: 'There was no sense in which people believed that they could cre- ate a future'. But the challenge of proving them wrong is one which Hall relishes.

It is easy enough to see how the artists at Dean Clough benefit from the commercial presence, which gives them both a source of patronage and a practical infrastructure. `I do a bit of teaching,' says Tom Wood, `and what I constantly stress is that a lot of time is spent not physically making art but doing something with it: transporting it ringing people up, photographing it. The beauty of Dean Clough is that it's all here for you — office facilities, faxes, parcel ser- vices, everything.' The mixture of large and small companies is also useful: 'The big companies give the place a stability which means you can plan in the long term; the small businesses engender a kind of work ethic, because they're the people you can identify with'.

Ernest Hall once defined his aim at Dean Clough as being `to put art into enterprise and enterprise into art'. The lat- ter is encapsulated by the 451°F bookshop, which was started two years ago by Paul Bradley, a sculptor who also runs the Henry Moore studio, and two painters, Shaun Pickard and Chris Sacker. Entirely designed and fitted by the owners, it spe- cialises in expensive contemporary art books. 'We couldn't afford a venture like this in Leeds or Bradford, let alone Lon- don,' explained Paul Bradley, 'because we couldn't afford the overheads. But we offer Dean Clough a service, and they look on us kindly in terms of rent.'

The converse proposition — that busi- nessmen profit from being surrounded by artists — is rather more difficult to prove, however inspiringly Ernest Hall talks of the artist being 'the ideal role model for the entrepreneur', relying on himself and his Imagination rather than a huge corporate structure. 'We are aware of the artistic side,' says Allan Templeton, the head of West Yorkshire Insurance, 'because every time we come here we pass through that gallery; but while he agrees that this con- tributes to the 'nice atmosphere' of the Place, the main attraction for companies such as his does seem to be simply that Dean Clough offers them tailor-made office space at a competitive rate. Doug Binder, who runs the gallery, argues that its effect — and that of the 500 original works of art scattered along the corridors of the complex — is largely sub- liminal. He also believes that ordinary peo- ple are more likely to accept the relevance of art to their lives if they come to realise that artists can be as hardworking and

down-to-earth as they are: 'It took the elec- tricians six months or even a year to talk to us, because they thought we'd be high- falutin' idealists. But when people see you in the process of mounting a show, which can take a week, they realise it's not the amateur thing they thought'.

`I call it a new democracy,' says Ernest Hall. 'I love the idea of bringing the Antho- ny d'Offay Gallery into a transport café. It's good for them too — it gives them a sense of reality.'

A more concrete example of the demo- cratic process is the way in which studio space is allocated at Dean Clough: appli- cants have their work vetted by all the artists already working on the site. But here too there is room for flexibility — on the day of my visit, two Bosnian refugees were being interviewed whose needs were con- sidered pressing enough to allow them to skip the waiting list.

Has the project benefited the area around it? In Halifax things certainly appear to be looking up: both the Northern Ballet and the Eureka children's museum have made their homes there; and the old Square Chapel has been restored as a cen- tre for the performing arts. The rest of the region may take a while longer, particularly after the blow dealt to it by the recent pit closures — though Hall is less despondent than some about this development:

`Three generations ago people were determined that their children shouldn't work down the pit. Now they say there's no future because there's no pit for their chil- dren to work in. People must be freed from this destructive idea that you can depend on the State, or society, or a company for your life; it is only through the increasing power of the individual that we can achieve economic prosperity. This is what I'm try- ing to promote here: the idea that miracles can happen — that people who have no apparent ability can develop incredible ability, given the right circumstances.'

Don't open the window, Agnes, some of those humans can be downright dangerous.'

Previous page

Previous page