COMPETITION

Self-review

Jaspistos

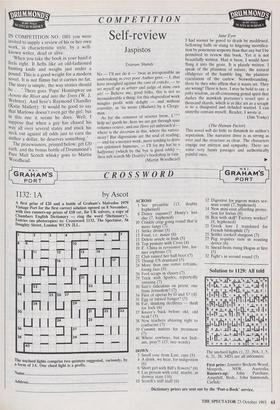

IN COMPETITION NO. 1801 you were invited to supply a review of his or her own work, in characteristic style, by a well- known writer, dead or alive.

`When you take the book in your hand it feels right. It hefts like an old-fashioned hunting knife and weighs just under a pound. This is a good weight for a modern novel. It is not flimsy but it carries no fat. The story is simple, the way stories should be • • .' There goes `Papa' Hemingway on Across the River and into the Trees (W. J. Webster). And here's Raymond Chandler (Katie Mallett): 'It would be good to say that Marlowe doesn't even get the girl, but in this one it seems he does. Well, I suppose that when a guy has chased his way all over several states and stuck his neck out against all odds just to earn the author a dollar, he deserves something.'

The prizewinners, printed below, get £20 each, and the bonus bottle of Drummond's Pure Malt Scotch whisky goes to Martin Woodhead. Tristram Shandy

No — Fll not do it — 'twas as irresponsible an undertaking as ever poor Author gave — I, that have inveighed against the cant of criticks, — to set myself up as arbiter and judge of mine own art! — Believe me, good folks, this is not so inconsiderable a thing: for this rhapsodical work mingles profit with delight — and without scurrility, as 'tis wrote (Madam) by a Clergy-

man.

As for the censurer of severer brow, L*** help us! quoth he, here we are got through nine volumes octavo, and our Hero yet unbreach'd where is the decorum in this, where the ratioci- nicity? But digressions are the soul of reading; — and for a merrier work, more tending to drive out splenetick humours, — I'll lay my hat to a halfpenny (which by the bye is good odds) thou wilt search Mr Dodsley's bookshop in vain.

(Martin Woodhead) Jane Eyre

I had sooner be gored to death by maddened, bellowing bulls or stung to lingering mortifica- tion by poisonous serpents than that any but I be permitted to review this book. Yet it is not beautifully written. Had it been, I would have flung it into the grate. It is plainly written. I speak of the plainness of nature; the natural effulgence of the humble ling, the plaintive ejaculation of the curlew. Notwithstanding, there be they who affirm that it wants art. They are wrong! There is here, I may be bold to say, a pithy wisdom, an all-consuming genial spirit that dashes the mawkish poetaster's vessel into a thousand shards, which is as like art as a seraph is to a dissipated and deluded wastrel. I can unnethe contain myself. Reader, I wrote it.

(Jim Yorke) (The Human Factor) This novel will do little to diminish its author's reputation. The narrative drive is as strong as ever and the structure as clear. The characters engage our interest and sympathy. There are some very funny passages and authentically painful ones. However, there are one or two small awkwardnesses (the first hints of age, perhaps?). Why does Daintry use the Americanism bring for take (page 16)? The Passiontide hymn serves a purpose, of course, and might be sung in October (page 67); similarly, Daintry, who didn't like beer (page 31), could have thought with regret of the strong beer at Stone's old chophouse (page 105), but both seem a trifle perverse. Why was Muller's chauffeur delayed in Watford (page 125), which has had a bypass for many years?

These are trifles, which can easily be put right in the not inconceivable event of a second edition; but wouldn't Castle have secured a passport for Sam years before?

(M. R. Macintyre) Under Milk Wood This is a Welsh froth, broth of a boiling play, meat-full of early summer soup, simmering in the kitchen's soul. It is night and daylight, song and sadness, and whining, rich as claret. It is drunk on the glasses of men's dreams, washing down the cheese and pickle suppers of a hundred indigestible heartburns. It is pub- punch-drunk in its phrases and popular pop peccadilloes. It is immortal in the immense immoralities of Nogood Boyo, petty-prim in the punctiliousnesses of Mrs Pugh. This is good beer with all the whisky chasers of the wet and watching world snuggling warm down the throat's welcome. This is money in the tight- pinching wallets of the wax-faced bankers, mopping up the spilled dregs of past misdoings, wiping out the glasses of dark-eyed debts and drubbings. This is Bells and Ballantynes, Glen- fiddich and Grants, Jamiesons and Johnnie Walker, bottles and (D. A. Prince) Rural Rides Now here is a book of inestimable worth, by a writer who thoroughly knows his business. He deeply loves his country, wore its red coat many years beyond the seas, knowing poverty and privation yet rising to the highest military rank attainable by those denied the despicable advan- tages of Privilege and Wealth. Mr Cobbett's

essays render in plainspoken, ringing tones his penetrating observations while ranging the country a-horseback. Himself a farmer's son, he excellently well informs our understanding of agricultural wretchedness, rural distress and the accursed oppression and neglect occasioning these conditions. Unafraid to condemn roundly, albeit in restrained language, the rapacious financiers, loathsome tax-gatherers and reptilian excisemen of the Great Wen, he is equally quick to marvel at the incomparable beauties of England's rolling downland and lovely vales, hanging woods and well-tilled fields. Truly, I would see this book, after the Bible, in every honest Englishman's hands.

(W. F. N. Watson)

Previous page

Previous page