WRIGHT'S LIFE AND REIGN OF WILLIAM THE F 0-U RT

H.

THESE goodly volumes are a singular specimen of the art of making much out of little. The naval career of Prince 1VILLIAM was so uneventful—the life of the Duke of CLARENCE so unim-

portant in public matters, and, with one equivocal exception, so

unmarked in private—that a very very small volume would suffice for his biography until he ascended the throne ; after which, save the back-stairs intrigues in which he was suspected of indulging, the acts of WILLIAM HENRY GUELPH belong not to biography, but to history. Nothing daunted, however, by the paucity of his matter, the Reverend G. N. WRIGHT has contrived to fill the re- quired space by the plan of writing roundabout his subject. Thus— the Sailor King was born in August; which gives occasion to an enu- meration of various events that have happened in that month, so pro- pitious, Mr. WRIGHT says, to the house of Brunswick. Amongst his sponsors, was the Duke of CUMBERLAND; upon which hint, we are favoured with a kind of biographical notice of the hero of Culloden. When Prince WILLIAM HENRY entered the navy, be happened to serve for a while in the fleet under Ronxelt, and was present in the action with LANGARA, (the only action of im- portance, by the by, in which he was ever engaged); whereupon we have a sketch of RODNEY'S career; and the same digres- sion is practised with nearly every Admiral under whom he served, or any officer of mark with whom he was in any way connected. The circumstance of the young midshipman having been in the fleet when some relief was thrown into Gibraltar, furnishes an opportunity of giving a short history of the siege; and a royal procession to return thanks for naval victories, got up to bamboozle the populace during the American war, is described at large, because his hero happened to be present in one of the battles. As his Royal Highness, for very sufficient reasons, was never employed after he had exhibited himself as a post-captain, whilst the Duke of YORK was engaged in active service and high command, this difference causes a diversion to the French Revo- lution and the campaign in Flanders. But as the Prince of WALEs was in the same predicament as his brother WILLIAM, the reader is favoured with an account of the Prince's line of poli- tics, as the probable cause of his disgrace, together with copies of the letters he wrote (or rather signed) to his father upon the subject. And so Mr. WRIGHT proceeds to the end of the chap- ter; except that, as the art of reporting and the practice of penny. a.lining improved with advancing years, he continually gets fuller and fuller as he approaches our own times. Although such a book can only be regarded as a trading compilation, and although it displays no merit beyond an unem- barrassed fluency, whilst it exhibits on the other hand the defects of an inflated style and a High Church spirit of ser- vile submission to the powers that be, yet are the volumes readable enough, and not without a kind of interest. As much of the matter consists of stories and anecdotes, transferred bodily from their original place without the trouble of alteration, they possess considerable character, freshness, and variety, and often give a picture of the manners and feeling of the age : the whole nar- rative takes the reader easily enough over the public and court events of an interesting period, reminding us, if not instructing us, about the American war, the French Revolution, and the Par- liamentary struggles between PITT and Fox, as well as of the dull homeliness of' the court of GEORGE the Third, the dissipated career of his eldest son, and the occasional " family jars" at St. James's. Those who do not dislike an olla podrida of history, biography, scandal, and court gossip, well diluted, will read Mr. WRIGHT'S Life and Times of William the Fourth not without pleasure. The successive steps in the progress of this royal personage are

so naked of circumstances, that they are only fit to be stated in a chronologicel form and put in the margin. In a general view, .his life may be considered under four points,-as a sailor, a peer, a private individual, and a monarch. As to his nautical course of Jife-the notions of strict punctilio which Geoaoa the Third enter- tained, coupled with no small share of skill in the claptrap at of

imposing upon the vulgar, compelled Prince WILLIAM to enter

the service and go through its regular gradations like anybody the. At present this would be a mere form : it is probable that the iron discipline of that day, the then exalted notions of quarter- deck authority, and the singular old English feeling-so regardful 'of the office, so regardless of the person-might render the Sailor King's probation roma] one ; not merely in such contrived effects as attending the Spanish Admiral hat in hand, as midship- man in command of the boat, but in respect of duty, buffets amongst his rnessmates, and exposure on service. Of his be- haviour during his career as a subordinate, only the usual kind of royal anecdotes are preservi d: private reports have whispered that he was by no means creditably distinguished for regularity of conduct, and that his roughness and rudeness so far exceeded what was even then expected from Jack ashore, that he often deserved, if be did not occasionally undergo, expulsion from assemblies into which his rank procured him admittance when in harbour. As a commander, the severity of his discipline is well known. Black Monday was black enough on board his ship ; stories are told of the unnecessary boat-servica to which he wantonly or unthink- ingly exposed his crew on the West Indian station under the mid- day glare of a tropical sun ; and he differed with Howe and NELSON as to the reality of the grievances that caused the mutiny at Spithead. His ideas of discipline, however, only extended to others. When, as a kind of indirect censure, he was ordered from the West Indies toQuebee, inwead of obeying, he sailed home. In snybody else, death i must have been the punishment: in the case of a Prince of the Blood, the Admiralty laid the whole of the papers before his father ; who ordered him to confine himself to the gar- ri-on of Plymouth, which harbour he had made, for as long a time as he ought to have remained on his station; and on the expiration of his durance, be was sent on another voyage -it was whispered to get him out of the way of a lady. But on his return he was shelved for life, though he rose accord- ing to the rules of the service. His frequent applications to the King 14 employment during the war received no answer, or one of formal refusal ; and when he begged, since the sea was closed against him, "to be allowed to ser.c his country by carrying a musket or trailing a pike as a velunteer" under his brother, the

request met with no better success. Mr. Witmer racks his brains in conjectures as to the cause. To us it appears as obvious as it was just,-even though his friendship with the Prince of WALes, in disgittee for his debts, and his doings on the Regency Bill, might not have aggravated the offence of disobedience.

As a senator, his want of education, and the narrowness and obtuseness of his intellect, prevented him from reaching beyond a very sober medioerity,-unless, perhaps, in p:actical professional matters, where experience is all in all. Even this experience was

liable to mislead him beyond his depth,-as on the slave-trade, of which he was the constant and unflinching advocate, relying on

what he had "seen" of domestic slavery in holy day trim. Besides nautical subjects, his Royal Ili4hness was great on divorce, both in principle and detail. He strenuously opposed the bill forbid- ding marriage between adulterers ; and opposed Bishop HonsLev in a long and learned speech, during which he took a survey of the law and practice of divorce under the Jewish dispensation, as well as in classical times. Who crammed him for the display, or whe- ther he read up for himself, is not recorded. In private life, he was odd, brusque, and hearty; prompt to

anger, and at times to rudeness, but generally ready to atone. He was exact and regular in his establishmeut; though his regularity did not, at one period, prevent his running into debt. The world is not in possession or the facts necessary to form a correct judg-

ment on his behaviour to Mrs. JORDAN. So far as is known, his conduct is indefensible on one point, and questionable on another.

He. put an end to the connexion suddenly, abruptly, and without assigned cause, or intelligible motive, unless it be the base one of " money," which Mrs. JORDAN conjectured. With respect to the penury, if not the destituti m, in which the molter of his children was allowed to close her life, the only possible excuse to be pleaded Is ignorance; which must have sprung from selfish indolence or

indifference. Even Mr. WRIGHT, though not an austere critic upon royalty, allows

. . . . o that the ca,c of this unfortunate woman wee a distressing one. The • chambers she occupied at Paris were shabby ; and no English comforts solaced her in her latter moments. In her little drawing room a small old sofa was the best-looking piece of furniture. On this she constantly reclined ; and on this she died."

We have so lately been called upon to review the character of WILLIAM the Fourth in his monarchal capacity, that it is unne- cessary to recur to the subject. It may however be observed, that in his kingly demeanour, he confounded plainness, perhaps coarse- ness, with dignified simplicity,-an error into which the unrefined are very liable to full. The heroic statues are mostly undraped, but it is not stripping off his clothes that will make a man a Hercules or a Theseus.

As the volumes tell nothing that seems to us new us regards the sultject, we shall glean a few miscellaneous extracts, which though not new either, have a livelier popular interest than the more germane parts.

accession to the throne, a Drawing-room was held at Sr. JaMes's Palace by the Prince of Wales and his sister the Prineess Royal. The novelty of th spectacle gave it peculiar attraction, and the. court was of course crowded with with the insignia of the Order of the Garter : on his right was the Prince' Bishop of Osnubmg, in blue and gold, with the Order of the Illth; next to him, on a rich sofa, sat the Princess Royal ; end at her tight hand, elegantly clothed in Roman togas, were the junior princes, William Henry, afterwards

Kent.

re appearance of so many fine children excited lively emotions in the cam.

ner in which the Heir Apparent and his sister deported themselves towards the about the Bishop ; and, hearing that Le would he eighty-two next Mnnday, Queen, " will go too." Mr. Bailer then dropped a hint of the additional the King, " requites contrivance ; but if I can manage it, we will all go." On the Monday following, the Royal party, consisting of their Majesties, the Prince of Wales, the Bishop of Osnaburg. Mince henry, the Princes' very modest air. I was pleased with all the Princes, but particularly with Prince William, who is little of his age, but so sensible and engaging, that he woa the Bishop's heart, to whom he particularly attached himself, and natal surprisingly manly and clever for his age; yet, with tile young Bullets, he was Caine, we are both boys, you know.' All of them showed affeetionate respect to the Bishop; and the Prince of Wales pressed his hand no hatd that he hurt

he might be himself unconscious of any greater truth than that be had lost the show. The procession was a very grand one, to return thanks for naval victories, and to deposit the captured co.

painter, and not to Barry, as sonic publications have stated. In the course of

Mr. Forbes, who was then a member of the Admiralty, Board, refused signing

King, but without effect. Admiral Forbes then indignantly gave up his seat, During the Administration of Earl Shelburne, afterwards Marquis of Lane downe, Admiral Forbes was asked to resign the office of General of Marines, as they proposed giving him a pension of three thousand a year and a peerage, to descend to his daughter. Admiral Forbes sent for answer, that the Generat. ship of Marines was a military employment, given to him by his Majesty as a and that he could not condescend to accept a pension, or to bargain for dpeer-

prove himself unworthy a the funnier honours he had received, by ending the

continued him in his military honours, and to the day of his death showed hue

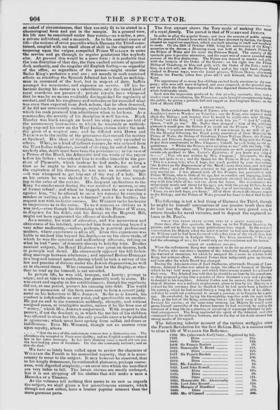

The following tabular account of the various strttggles since the French Revolution for the first Reform Bill, is a curious scrap to close a life of WILLIAM the Reformer.

1793. Mr. (afterwards Earl) Grey Negatived by 241. 1797. Ditto 165.

1800. Ditto 15429..

1809. Sir Francis Burdett

1810. Honourable T. Brand 111217)

1812. Ditto

1817. Sir Francis Burdett 189.

1818. Ditto 106.

1819. Ditto 95.

1821. Mr. Latubton 12.

1821. Lord John Russell 31.

1822. Ditto 105.

1623. Ditto 98.

1824. Ditto

1825. Honourable Mr. Abercrotnhy 24.

1826. Lord John Russell 124.

1829. Marquis of Blandford 74.

1830. Ditto 119.

11330. Mr. O'Connell :306.

to pay their compliments to Mrs. Chapone; himself, he sod, being an old at. quaintance. " Whilst the Princes were speaking to me," adds the lady, "Xs it-.' (This ode was written by Mrs., Chapone.] Afterwards, the King [the Letters on the Improvement Te the Iliad,] more than once, and will read Royal, and Princess Augusta, visited the Bishop. The King wint the Priam

cettain ode ptefixed to Mrs. Carter's Epietetns; if you know soy thing of

Arnald, the sub-preceptor, These gentlemen are well acquaiuted with a

came and spoke to Us; and the Queen tel the Princess Royal to me, s:Lying,

' This is a young lady, who, I hope, has much profited by your instructions them often ; ' and the Princess assented to the praise which followed with a

of a royal family. The period is that of WILKES and JUNtus.

into the peaceful channel from which it had been diverted by faction, the Queen adopted an ingeninus expedient, which was both pleasing in itself and ben • In order to allay. the popular frenzy, and turn the current of public opinion

The first extract shows the Tory mode of making the emfieoiseti

to trade. On the 25th of October 1769, being the anniversary of the King's persons of the first distinction. The Prince was dressed in scarlet and gold William the Fourth, (then four years old !) and Edward, the late Duke of

pany.; who were still more delighted, and even surprised, at the graceful man- whole fashionable circle. Such was the impression prodneed by this pleasing spectacle, that, with a similar view to conciliation, the Prince was again brought conspicuously before the public, by giving a juvenile ball and supper at Buckingham House; on the lath of March 1770.

A REGAL VISIT,

Mr. Buller (afterwards Bishop of Exeter, who married one of the Bishop daughters) went to Windsor on Saturday ; t‘aW the King, who inquired much

" Then," said the King, " I will go and wish him joy." " Anil I," said the pleasure it would give the Biehop if he could see the Princes " That,'' said

stay with him while all the test ran about the house. His conversation WH

quits the boy ; and said to John Buller, by way of encouraging him to talk, it."

The following is not a bad thing of GLORCE the Third, though

lours in St. Paul's.

WHAT THE FIRST STATE ACTOR SEES IN A STATE PAGEANT.

Some days after this spectacle, the King sat to Sir William Beechey, the conversation, his Majesty tidied the artist whether lie hail seen the proce-sion? Sir William said he had been favoured with a tine view of the whole line, from an excellent situation in Ludgate Street. The King answered, " Then you

had the advantage of lime; for I could only see the coachman and his horses." SPIRIT OF ADMIRAL roanes.

When the unfortunate Byng was sentenced to die for an error of judgment, the warrant of execution, for which he assigned his rsasons in a letter to the and soon after the whole Board was changed.

which he ba1 held many years, and which Government wanted for a Li lend of their own. The Admiral was told that he should be no loser by his compliance, reward for his services; that he thanked God he had never been a burden to his country, which he had set ved during a long life to the bet of his ability; age. Ile concluded, by laying his Generalship, together with his rank in the Navy, at the feet of the King, entreating him to take both away if they could forward his service; at the same time assuring his Majesty he would never

remnant of a long life on a pension, or accepting of a peerage obtained by pole

tical arrangement. The King applauded the spirit of the Admiral, ever after strong marks of his regard.

Previous page

Previous page