England's other province

John Biggs-Davison

Eamon de Valera described Ulster as Ireland's 'fairest province . . that the Irish of every province love best next to their own. The Ulster of Cu Chulainn, the Ulster of the Red Branch Knights, the Ulster of the O'Neills and the O'Donnells. The Ulster of Benburb and the Yellow Ford ...'

The Ulster of Benburb! There, on the borders of what is now Co. Tyrone, the 'Old English' Catholic, Owen Roe O'Neill, scored by 'push of pike' a brilliant victory over forces to be identified in Irish folk memory with the 'curse of Cromwell'. 'Old English' and Gaelic Irish did doughtily then for the Scots King of England and of Ireland—and the Pope attended a Te Deunz in S. Maria Maggiore.

And they sang Te Deum in Catholic Vienna for the victory of the Boyne—which has been made a perverse sectarian myth. At the Boyne there were Catholic soldiers on William's as well as the Jacobite side.

A Paisleyite may invoke the shade of Cromwell. King Billy looks down from his saddle upon the Orange Halls. It was a Pope, admittedly English, who gave Ireland an English or Anglo-Norman King. The Plantations were Catholic under Mary before ever they were Protestant under Elizabeth and James I. Yet Ulster Protestants denounced Cromwell's judicial murder of King Charles I and the Conservative and Unionist Party traces its origins to the constitutional Royalists like Hyde and Falkland who first opposed, then championed, Charles, standing as they did for the Church, the King—and the laws. The titles 'Tory' and 'Whig' arrived with the attempt to exclude the Catholic James Duke of York from the succession to Charles II. Tories were popish Irish bandits, Whigamores Scotch Covenanters. In the vivid language of the Reverend Titus Oates, 'These then for their Eminent Preying upon their Country, and their Cruel, Bloody Disposition, began to show themselves so like the Irish Thieves and Murtherers aforesaid, that they quickly got the name of Tories.' Which name of opprobrium the British Conservative, like the 'Old Contemptibles', proudly bears as a badge of honour.

My grandfather, a Presbyterian minister from Co. Down, told my mother that Tories were people born bad who got worse! A Liberal Home Ruler, he was not far out of line with the tradition of 1798—of the United men of Antrim led by the Presbyterian Henry Joy McCracken or the rebels in his own county of Down incited by the Presbyterian minister of Saintfield.

Ireland then offered, as often in her history, oppurtunities for England's enemies. The ideology of the French Revolution, an ideology hostile to the Church, was exported on the bayonets of Bonaparte, who lamented in exile in St Helena that he had gone to Egypt rather than to Ireland. No more strange then than the myth of the Boyne is the tradition of '98. It is ironic that the rosary should be recited in Bodenstown at the grave of Wolfe Tone who knew no Irish, nor much of Ireland beyond Dublin and Belfast, who sneered at 'poor Pat' and his faith, and rejoiced when his patron, Napoleon Bonaparte, dethroned the Pope and sent hime into exile. By liberating Ireland, he would free her from popish superstition. In his own words, 'The emancipated and liberal Irishman, like the emancipated and liberal Frenchman, may go to Mass, may tell his beads, sprinkle his mistress with holy water; but neither the one nor the other will attend to the rusty and extinguished thunder bolts of the Vatican ...'* But mighty is myth in the distortion of the terrifying simplifiers. Place beside the Orange inventions the extravagances of Padraig Pearse who declaimed at Bodenstown in 1913: 'We have come to the holiest place in Ireland : holier to us even than the place where Patrick sleeps in Down.'

Pearse wrote: 'God spoke to Ireland through Tone.' But for Pearse Christ was not so much the Prince of Peace as the 'King that was born' to 'help the Gael'. There is not much that is Christian about Pearse's detestation of the English (his father was one of them!) as a race inferior to the Gael, morally, intellectually and in their 'mongrel' language. The blood sacrifices of 1798 and 1916 were without santion of the Christian Church. Tone and Pearse were men of hate.

Jacobitism was a more authentic Catholic tradition in Ireland than Jacobinism. The watchword of the Catholic Confederacy of Kilkenny was 'Pro Deo, pro Rege, pro Patria Hibernia unanirnis', The Gaelic-speaking and Catholic peasantry in Monaghan and elsewhere constituted the mass of the militia that defended the British Crown against the French Republic and crushed the United Irishmen. Sinn Fein could be dual monarchist and was only latterly Republican. De Valera himself conceded that Ireland free might choose kingship, but astutely insisted the wearer of the crown should not be of the House of Windsor.

History at least affords no warrant for the identification of Catholicism with separatism—the first great nationalist leaders were

protestant—or of Unionism with Protestantism. The Catholic Lord Edward Talbot contributed to the fighting fund of James Craig, r of Craigavon. True, he added the caveat that 'if 1 find it is•being used in an attack on orthodox, and not Hibernian P,PPerY, I shall have to come over and study the best means of incendiarism on Craigavon.' Yes, there was a Hibernian Popery Which sought to enlist the Church in the nationalist cause and an Ancient Order of 111bernians which played the opposite political role to that of the Orange Order for w. hose disaffiliation from the Ulster Unionist Party I have pressed from Unionist Platforms

In .

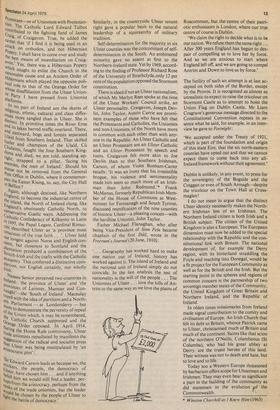

nopart of Ireland are the skeins of 'etIglous, ethnic, cultural and class differences more tangled than in Ulster. She is distinct in primitive times the River Erne arid its lakes barred traffic overland. There, and eastward, bogs and forests separated hurler from Southern Ireland. That skilled nurler and champion of the Ulaid, CCi Chulainn, fought the four Southern Kingdoms and died, we are told, standing up rig strapped to a pillar, 'facing his enemies, the men of Ireland.' Should his statue not be removed from the General p cist Office in Dublin, where it commemorates the Easter Rising, to, say, the City Hall in Belfast?

t, Again, although destined, like Northern cngland, to become the industrial centre of the island, the North of Ireland clung, like fligland's obstinately Catholic North, to Conservative Gaelic ways. Addressing the Catholic Confederacy of Kilkenny in Latin la, 1695, the Papal Legate, Cardinal Rimucclnl described Ulster as 'a province most tenacious of the true faith . . .'. Ulster held out I „ •ongest against Norse and English con',Pest, but closeness to Scotland and the „Piantation produced a combination of the '3cotch-I risfi and the crafts with the Catholic rle,asantry. This conferred a distinctive corn h "r'exion, not English certainly, nor wholly , Nassau Senior perceived two countries in "'eland: 'the province of Ulster' and 'the Provinces of Leinster, Munster and Conilughl'—the 'South of Ireland'. Macaulay toyed with the idea of partition and a Northern Parliament Parliament — at Londonderry — but nl°re to demonstrate the perversity of repeal 0 r the Union which, it may be remembered, the Catholic Church supported and the Orange Order opposed. In April 1914, during urIng the Home Rule controversy, Ulster jade unionists repudiated by manifesto the aggestion of the radical and socialist press 'hat Ulster was being manipulated by 'an aristocratic plot' : :Sir Edward Carson leads us because we, the w..orkers, the people, the democracyof ISter have chosen him ... and if anything h. 'ell him we would still find a leader, perdPs from the aristocracy, perhaps from the ranks of the trade unionists, but the leader ;Pold be chosen by the people of Ulster to light the battle of democracy.'

Similarly, in the countryside Ulster tenant right gave a popular basis to the natural leadership of a squirearchy of military tradition.

Self-determination for the majority in six Ulster counties was the concomitant of selfdetermination in the South. An embittered minority gave no assent at first to the Northern-Ireland state. Yet by 1969, according to the finding of Professor Richard Rose of the University of Strathclyde, only 12 per cent of the population opposed the Stormont constitution.

There is ideed if not an Ulster nationalism, of which Mr Merlyn Rees spoke at the time of the Ulster Workers' Council strike, an Ulster personality. Craigavon, Joseph Devlin, John Taylor, Austin Currie are prominent examples of those who have felt that the Protestants and Catholics, the Unionists and non-Unionists, of the North have more in common with each other than with anyone in the Republic. An Ulster Catholic and an Ulster Protestant are an Ulster Catholic and an Ulster Protestant by speech and roots. Craigavon felt more akin to Joe Devlin than to that Southern Irishman, Carson, of whom Violet Bonham-Carter recalls: 'It was an irony that his irresistible brogue, his violence and sentimentality made him seem so much more of an Irishman than John Redmond.'* Frank McManus, formerly Republican Irish Member of the House of Commons at Westminster for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, discussed reunification of the nine counties of historic Ulster—a pleasing conceit—with the hardline Unionist, John Taylor.

Father Michael Flanaghan, who after being Vice-President of Sinn Fein became chaplain of the first aid, wrote in the Freeman's Journal (20 June, 1910):

. . Geography has worked hard to make one nation out of Ireland; history has worked against it. The island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide. In the last analysis the test of nationality is the will of the people . . . The Unionists of Ulster .. . love the hills of Antrim in the same way as we love the plains of Roscommon, but the-centre of their patriotic enthusuasm is London, where our true centre of course is Dublin.

'We claim the right to decide what is to be our nation. We refuse them the same right ... After 300 years England has begun to despair of compelling us to love her by force. And so we are anxious to start where England left off, and we are going to compel Antrim and Down to love us by force.'

The futility of such an attempt is at last accepted on both sides of the Border, except by the Provos. It is recognised as almost as unrealistic to expect to raise the tricolour on Stormont Castle as to attempt to hoist the Union Flag on Dublin Castle. Mr Liam Cosgrave's generous message directed to the Constitutional Convention repeats in essence what he said, for example, in an interview he gave to Fortnight: 'We accepted under the Treaty of 1921, which is part of' the foundation and origin of this state Eire, that the six north-eastern counties have opted out and that we cannot expect them to come back into any allIreland framework without their agreement.'

Dublin is unlikely, in any event, to press for the sovereignty of the Bogside and the Creggan or even of South Armagh—despite the tricolour on the Town Hall at Crossmaglen !

I do not mean to argue that the distinct Ulster identity necessarily makes the Northern Irishman less of an Irishman. The Northern Ireland citizen is both Irish and a British subject. The citizen of the United Kingdom is also a European. The European dimension must now be added to the special relationship with the Republic and the constitutional link with Britain. The national development of, for example the Derry region, with its hinterland straddling the Foyle and reaching into Donegal, would be a fit project for the European Community as well as for the British and the Irish. But the starting Point in the spheres and regions of common concern is the partnership of two sovereign member states of the Community, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland.

In olden times missionaries from Ireland made signal contribution to the comity and civilisation of Europe. An Irish Church that felt its debt to Britain, whence Patrick came to Ulster, christianised much of Britain and much of the continent. Saints like that scion of the northern O'Neills, Columbanus (St Columba), who had his great abbey at Derry, are the truest heroes of this land. Their witness was not to death and hate, but to love and to life.

Today too a Western Europe threatened by barbarism offers scope for Ulstermen and Irishmen. They may even bear as significant a part in the building of the community as did statesmen in the evolution of the Commonwealth. 1`, • Winston Churchill as I Knew Him (1963)

Previous page

Previous page