The Good Life

One's own thing

Pamela Vandyke Price

There are many problems involved with being gastronomic: weight, all the frightful wines and ughsome foods one tastes for the benefit of readers who need not, and the bills for the necessities of life which actually require earned cash to procure. But gastronomic people are fortunate because, preoccupied as most are in getting on with the cooking, the tasting, or the churning forth of winged words about both, they have not the slightest wish to do anyone else's job. Never do you hear a cook, dining luxuriously in some temple of cuisine, express a longing to get into that' kitchen. Nor can one imagine Baron Eli de Rothschild scheming to take over Mouton, or Baron Philippe to buy up Lafite.

So we shall not be exposed to what I fear may be a spate of happenings that do not happen, after the recent Albert Hall concert where, one baritone having sunk down overcome by heat, and the understudy — a doctor — tending the casualty, lo! on to the stage surges a singer who happened to be there, who happened to have the score and who happened to be able to sing the part. Nice' Hollywood though that was, I do not relish the prospect of attending operas cheek by, literal, jowl with putative Brunnhildes in plaits and cuirass, evenings at the ballet where my slightest twitch brings a fierce "Mind my tights!" from the embryonic Nureyev in the adjacent stall.

No, people may, in the security of their closets, tell their dearest friends that of course, they mustn't say nasty things about A, B and even C (he's getting on now), but actually they themselves are the world champions in the profiterolle stakes, they make the finest wine, have stocks of the rarest cordials and pen the most succinct tasting notes — without boasting for a second, though they are delighted to see A, B and poor old C tottering on with their own work. Never do we curdle the Béchamel or vinegarise the grand cru with base thoughts. And indeed, in the great restaurant of this world there is, happily, a slice of cake to go round to al].

The Best of Eliza Acton was first published in hardback by Longmans — lucky them, Miss Acton brought them her first manuscript in 1845 — and now Penguin have produced the paperback edition, for the astonishingly low price of 75p. This would be enough, but the contributions of Elizabeth Ray, who edited the selection, and Elizabeth David, who wrote the introduction, make the book a bargain twice over. Miss Acton possessed great elegance of style in writing which, rather like true clothes sense. is never allowed to obscure the important end to which it is a means — in fashion, the enhancement of the individual, in writing about food, the clarity of the instructions and the encouragement of the readet , so that the thing that is cooked or prepared is enjoyable. She has a sense of humour — could one cook or choose wine without it, when one considers the comicality of the odd disasters? — and is wholly practical. Mrs David says of Miss Acton's Modern Cookery "for twenty years the book has been my beloved companion." Mrs Ray says "the recipes are set out as well and as clearly as any I have come across." To read Miss Acton, even without being impelled to the kitchen, is to receive a refreshing stimulus of sense about cooking and a knowledge of what is a reasonable short cut and what is a false economy. Would that she might have castigated the con cocters of bad boeufs Wellington, the producers of battery-bred poussins, farcis, sur canapa, gami en croCite and flambe with the nastiest kind of Balkan liqueur unknown since the end of the Empire! Would, indeed, that I might have been the fourth Elizabeth in this delectable marmite (though as I narrowly escaped Wendy on the distaff side and Gladys on t'other, I cannot really complain). But "the gastronomic person who does not possess their own copy of Eliza Acton" should be cast into sliced bread and uncow everlasting milk.

Pamela Vandyke Price is also wine correspondent of the Times

Previous page

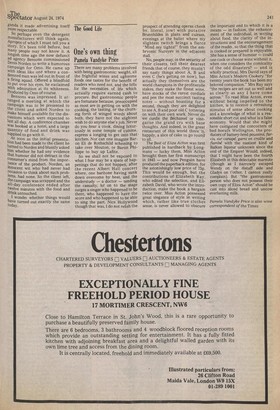

Previous page