THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Annus Horrendus In. Urbe

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

TN the forecourt of the remarkable new Roths- 'child ollice in St. Swithin's Lane (which no student of modern architecture should miss) there is a vast slab of stone or concrete which seems to be an empty altar waiting for the image of the golden calf. A wit told me in passing that it was the altar on which the bank sacrifices its clients. But I have thought of a better use—a *statue of Mr. James Callaghan strangling the professional investor whose limp hand is drop- ping a bundle of dollar securities.

This has been a year of near-disaster for the professional investor and a year of austerity for the jobbers and brokers who make a living out of the capital market. The Budget with its twin revolution in the taxation of capital gains and corporate profits was the prime cause of it all. The successful management of an invest- ment portfolio depends on clever and continual 'switching.' As markets move up and down under the influence of changing money rates and profits the managers have always tried to switch from the securities they consider temporarily dear into those they consider temporarily cheap. It is a skilled and risky job but by and large it pays. It is surprising how regularly the investment trusts managed to beat the market indices in the annual reports of their funds. But put a heavy tax on all this 'switching' and the investment business dries up. The life assurance companies who are the biggest investors in the market—with about £5,000 million of Stock Exchange securities— have to pay capital gains tax at the corporation tax rate with a ceiling of 374 per cent. The investment trusts with £3,000 million and the unit trusts with £520 million of• securities have to pay on gains at the rate of 30 per cent (a con- Cession rung out of Mr. Callaghan to bring them into line with the individual taxpayer's rate). A gains tax ranging from 30 per cent to 374 per cent makes 'switching' in equity shares far too risky for the average cautious professional in- vestor. So the turnover in equity shares on the Stock Exchange ,has fallen sharply—from £981 million in the first- quarter of the year to £704.8 million in the third. It is small wonder that several jobbing firms in the industrial markets have closed down and left the City. In the gilt-edged market the tax on switching has made the managers of life funds throw in their dealing hands. In November the turnover in British government bonds had dropped to 11,112 million from the quarter's monthly total of 11,625 million. Several jobbing firms in the gilt- edged market have closed down and more have

merged with or have been taken over by bigger firms. Throgmorton Street, as I have said, has become virtually a distressed area. I appreciate that this will not trouble most readers of this column but I warn them not to expect in the next five years such good results from their holdings in the unit trusts and investment trusts or such good bonuses from their with-profit life policies over the next ten.

Here is a warning also to the brave man who tries to look after his modest capital on his own account. This year's experience will per- haps make him regret that he ever followed the so-called 'cult' of the equity. It is true that the Financial Times index of industrial ordinary shares will finish the year at a slightly higher level than it started, but see what has happened in the markets since the Budget. After a hopeful pre-Budget rise share prices fell sharply and horribly for six months and the recovery which followed in the last three months was due simply to the fact that the professional managers were bringing home a lot of money from Wall Street and having to reinvest it in a market which was short of stock.

The Budget, of course, hit some groups more than others. The property companies and the oil companies and others operating overseas had the biggest taxation shock of all. All these groups have suffered market falls from 20 per cent to 334 per cent and are recovering now mainly because of technical market conditions. Heavy underwriting losses from American hurricanes and riots added to the taxation troubles of the composite insurance companies and some of

their shares are still 30 per cent to 40 per cent below their high prices of 1964. Steel shares have also behaved in a maddening fashion. On the nationalisation proposals they rose by over 25 per cent and then lost half the rise in the last six months as company profit margins wor- sened. Breweries, ordinarily a stable group, fell by nearly 20 per cent between February and July and recovered only half the fall thereafter. On the whole it has been a dismal story and in- dividual investors will have been lucky to have ended the year with their portfolios, like the Financial Times index, slightly higher in value than at the beginning of the }ear.

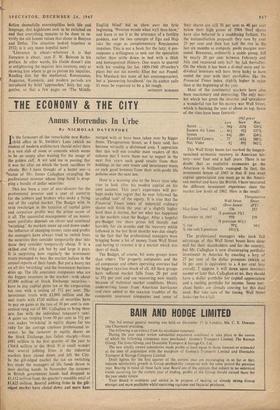

Most of the continental markets have also been reactionary and depressing. The only mar- ket which has given the investor and speculator a wonderful run for his money was Wall Street, which is finishing the year at about its top. Some of the rises have been fantastic:

Low 1903 prices Now Rise

Xerox .. 94} 2134 124% Eastern Air Lines .. 414 97.4 137% Syntex

64;

209 224%

Fairchild Camera .. 27

1634 500%

Nat. Video .. 8;

894 962% This Wall Street boom has marked the longest- sustained economic recovery in American his- tory—over four and a half years. There is no doubt that as capitalist economies go the American is brilliantly managed. In fact, the investment lesson of 1965 is that if you want capital appreciation you must go to the Ameri- can market and leave the British. I have measured the different investment experience since the market low levels of 1962. Here is the result:

Throsmorton Wail Street Street (Dow Jones) (FT) 536 253 premium 3%) 959 339 premium 16%) 79% 34% 1014%

The professional managers who took full advantage of this Wall Street boom have done well for their shareholders and for the country, but Mr. Callaghan is now discouraging portfolio investment in America by exacting a levy of 25 per cent of the dollar premium (which at 16 per cent is equivalent to a 4 per cent levy overall). I suppose it will dawn upon investors sooner or later that, Callaghan or no, they should have a dollar portfolio for capital appreciation and a sterling portfolio for income. Some mer- chant banks are already catering for this dual need. But take care of the timing. Wall Street looks ripe for a fall.

•

May-June 'lows' 1962 ($ December 16, 1965 ..

% rise % rise with $ premium

Previous page

Previous page