'THIS FOOLISH DAY'S SOLEMNITY'

Michael Trend investigates

the attempts to have Christmas abolished

EVERY year in late December, as the wits of the press scratch their heads to come up with a suitable seasonal offering, we hear the suggestion — passed off, every time, as original — that Christmas ought to be privatised. Sell it off to the highest bidder, float it on the stock exchange, or — the next best thing — deregulate it! (How we all roll about laughing.) Then, over the warm British sherry at Mrs Snooks's Christmas drinks party, you often also hear that Christmas was utterly deregulated — abolished — by Oliver Cromwell. This belief, which lies deep at the back of English folk-memory, is one that I had heard often enough to want to know if it really was true.

And true it is. The House of Commons Journals show that for 11 of the years between 1643 and 1656 the House sat on Christmas Day; two of. the three years it missed were Sundays (when the Puritans would not do anything apart from listening to improving sermons) and in the other year the House had already been dis- solved. Parliament did not revert to the old practice of taking Christmas off until the Restoration in 1660. Moreover, the attempt to abolish Christmas for the rest of the population was not a single, isolated event but a continuous obsession with some of the Members. On a number of occasions the Commons, working away at its tedious business on this day, tried to enforce its will — to be 'done with' Christmas — on the populace at large.

There was, first, an ordinance in 1644 that Christmas, which that year fell on a Wednesday, should particularly be observed as a fast day — as all the last Wednesdays of the month were then 'cele- brated' (to use their language). The Puri- tan note was already being clearly sound- ed: the feast of Christ's birth had been turned into 'an extreame forgetfulnesse of him, by giving liberty to carnall and sen- suall delights'. By 1650 the pace had hotted up and the Council, upset that shops were being shut up on 25 December, when the people ought rather to be keeping them- selves busy, thought fit 'that the Parlia- ment be moved to take . . . further Provi- sion and Penalties for the Abolishing and Punishing of those old, superstitious Observations'. Two years later a resolution was passed that the markets and shops be kept open on Christmas Day and that the Mayor and sheriffs of London and Mid- dlesex should ensure that this was done.

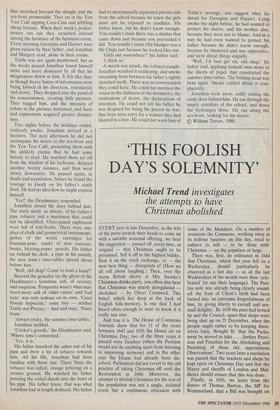

Finally, in 1656, we learn from the diaries of Thomas Burton, the MP for Westmorland, that a Bill was brought on 25 December by Colonel Mathews 'to prevent the superstition [of observing Christmas] for the future'. First to speak was a Mr Robinson who told the House that 'I could get no rest all night for the preparation of this foolish day's solemnity. This renders us, in the eyes of the people, The great debate: Father Christmas warned off by a Puritan and welcomed by a merry-maker. From The Vindication of Christmas', 1653.

to be profane.' Another speaker observed that 'one may pass from the Tower to Westminster and not a shop open, nor a creature stirring'. The House desired the Bill to be given its first reading and to be read for the second time on the morrow. That, however, does not appear to have been done and in the next year Mercurius Politicus tells us (the House was adjourned at the time) that 'his Highness' (as Crom- well had become) had made an express order 'abolishing the observation of the day commonly called Christmas', partly because it was obnoxious to the ruling powers as a religious festival and partly as 'disorderly people are wont to assume to themselves too great a liberty'.

The 'eyes of the people', however, were still firmly on the former liberties and it is clear that throughout this period many were not paying much attention to the Ordinances, Orders, Remonstrances and Bills. There were serious riots at Bury St Edrhunds in 1646 and at Canterbury in the following year brought on by the zealots trying to force those they called the 'Malig- nants' to open up their shops on 25 December.

In Canterbury, a contemporary account tells us, the news that Christmas Day should be 'put downe, and that a Market should be kept' was 'taken very ill by the country'. A riot ensued in which heads were broken; the crowd went to 'one Whites a Barber, (a man noted to be a busie fellow) whose windows they pulled down to the ground'. In Bury St Edmunds the `bloudy Designes' of the 'Malignant Party . . . against the People of God, and the Members of Jesus Christ . . . were frustrated, and [their] mischievous and machivalian Plot discovered'. The pro- Christmas faction appeared, we are told, 'in a most vild and bloudy shape; for these wicked Members of Sathan, and enemies to God and Religion, had so conspired together, against the people of God, that they were resolved to prosecute their Designe, in case that any one of them should presume to open their shops on Christmas day, and to that end had pre- pared divers weapons for the execution of the same'.

There was trouble too in London. The effect of the Commons' resolution of 1652 was reported on the day following Christ- mas in the pro-Parliamentary journal the Flying Eagle: 'Nulls the mother Church, and all her daughters, languishing without the old and usual mirth of Bels, Bellowes and Bag-pipes, Taverns and Taphouses having all the custome, Bacchus bearing the Bell amongst the people . . . it was as rare a thing to see a shop open, as to see a Phenix, or Birds of Paradice.' In 1656 troops were out on the streets again to round up `malignants' and they apprehended the following three preachers — whose names I mention honoris causa — Mr Thisscross in Westminster, Dr Wilde at a meeting in Fleet Street and Mr Gunning at Exeter House in the Strand.

From these and other records one can see that there were two arguments at work here. First, the Puritans had a deep-rooted objection to what they saw as the disorder — both personal and civil — that was traditional at this time of year. The Flying Eagle was disappointed that people still took the opportunity to drink heavily 'as if neither Custome nor Excise were any burden to them'; the people were worship- ping 'their soveraign Lord their belly'. Those on the pro-Christmas side put up a spirited and entirely serious defence of the use of holly, ivy, misletoe, rosemary, bay, 'plum-pottage and minced-pies' which were associated with the former festival.

The Puritans went further, however, and argued that Christmas should not be a festival at all — that it was (as one also often hears said today) a pagan feast: Saturnalia only lightly veneered with the Christian religion. The two arguments were often conflated, as in Thomas Mock- et's work of 1650, which attacked the 'heathenish customes, and Pagan rites and ceremonies that the idolatrous Heathens used, as riotous Drinking, Health- drinking, Luxury, Wantonnesse, Dancing, Dicing, Stage-plays, Enterludes, Masks, Mummeries with all other Pagan sports, and prophane practises'. Moreover, there was a strong attack on Christmas as a feast likely to perpetuate the influence of Rome — 'the Papists Massing day', 'Antichrists Masse'.

But there was also a more theological front to their assault with reviews of Biblical evidence setting out to show that Christ's birth had been `misse-timed', often based on trying to establish the time of John the Baptist's conception (for those who are interested in such matters and are fed up with eating 'minced-pies' the key texts are Luke i 5 and 1 Chronicles xxiv 10). Among other arguments used (which include the old shepherds-in-the-field routine) was one I thought particularly charming: `Seveqthly, neither is it likely that the Wisemen that came to visite Christ, were so unwise, as to take so long a journey to, and from Christ, in the depths of winter.'

The opposition hit back. Their theo- logically-minded pamphleteers also argued over the Biblical evidence. Against the charge of excess one of them, George Palmer, advanced the view that 'the best things have been abused'; moreover, the celebration of Christmas was promulgated to the shepherds and should continue to be spread to the world as it helps counteract those who say that Christ did not come in the flesh (one in the eye for the Bishop of Durham, I thought). We also hear an unusual defence of mince-pies: that one should 'taste and see how Sweet our Lord Jesus is'. Other pamphlets, designed for a more popular appeal, put the matter more dramatically. In one, `Women will have their will', we find Mistress Custome laun- ching a sharp attack on Mistress Newcome on the matter of the Parliamentary ban: 'Fie upon'( . . . I do not know this Parlia- ment, 'tis no kin to me . . . this is worser Authoritie than my husband.' To the charges that people at Christmas misbe- have themselves and make gods of their bellies she puts forward the cunning notion that 'if it were not for the Dancing, Frisking, Playing, Toying, Christmas- Gamboles, and such kind of jogging Exer- cises to shake it down, it were impossible they should devoure so much as they do'.

The pro-Christmas faction presented the Puritans as spoil-sports CI see you are . . . a great Student in Spittle-Colledge,' said Mistress Custome to Mistress Newcome) and as miserly, miserable men of com- merce: in The Vindication of Christmas old 'father Christmas' himself comes to town

where I entered a fair house that had been an Aldermans, but it was now possest with a grave Fox-fur'd Mammonist, who I found sitting over a few cinders to warm his gouty toes; from head to heel he was fur'd like a Muscovite, & instead of a Bible he had a Bond in his hands, which he poar'd upon to see if it were forfeit or no; but when he espyed me, he cry'd Traytor, Traytor.

Worse, it seemed to some of the pro- Christmas camp, was the attack on alcohol: 'our high and mighty Christmas-Ale that formerly would knock down Hercules, & trip up the heels of a Giant' had been struck 'into a deep Consumption with a blow from Westminster'. We learn else- where that business was bad for 'Candle- makers, Cardmakers, Cookes, Pimakers'. The Complaint of Christmas has 'father Christmas' himself, 'put into a Browne study', asking, 'Can any Christian or Col- chester man tell poore old Christmas day where he is? Is this England or Turkey that I am in?'

We can see, then, that during the Com- monwealth the celebration of Christmas was a continuing tension in the country. Old Christmas himself, however, was going to get away in the end. In The Arraignment of Christmas we see this vividly. Here we have Mr John Woodcock, a 'Fellow of Oxford', writing to his lady in London for information on the whereabout of Christmas. In past years he has given her, she says, 'many a hug and Kisse in Christmas time when we have been merry'. Woodcock is trying to raise a hue and cry for 'an old, old, old, very old, grey bearded Gentleman, called Christmas' whom he fears is lost; she replies that 'the poor old man upon St Thomas his day was araigned, condemned, and after conviction cast into prison among the Kings soldiers, fearing to be hanged, or some other execution to be done upon him'. But he escaped. Christ- mas 'broke out of Prison in the Holidays and got away, onely left his hoary hair, and grey beard, sticking between two Iron Bars of a Window'.

Previous page

Previous page