A ROMANTIC MANIFESTO

Miss Lucinda Tyrrell explains

why she dresses up in funny clothes

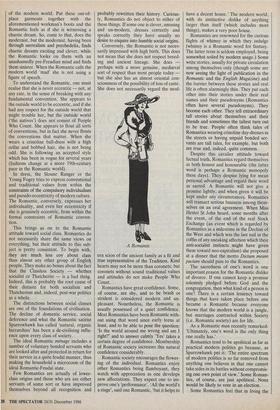

THE average Romantic is female, well- educated, and somewhere between 18 and 45. She is female for what are called `historical reasons'. The Romantic move- ment is said to have been born, or at any rate gestated, in an Oxford women's col- lege which did not at that time admit men. The Romantic inhabits an imaginative world, which, perhaps, women feel freer to do in these days. She genuinely finds the modern world mad and impossible to take seriously and sees her own Romantic 'bub- ble' as an oasis of sanity. When people accuse her of turning her back upon reality one imagines her (if she deigned to answer at all) gesturing disdainfully at the modem world and saying: 'You mean that?'

Her clothes are what one first remarks about her, but, though they may be strik- ing, it is the way she wears them that really marks her out as a Romantic. Whether she wears crinolines or Thirties chic, or one of the 'neo-hyphen' or eclectic styles, she wears them with utter self-consciousness and completeness. It is this self- consciousness, this completeness, both in dress and in manner, which distinguishes the Romantic from other modern types and indicates that she is essentially not modern. The Sloane Ranger will wear jeans under a Savile Row overcoat for 'counterpoint'. The Voguette will wear workman's boots under lacy Victorian petticoats. The Young Fogey will wear the coat of a pinstripe suit with grey flannels and a fawn cardigan. The Romantic sees all these things as modem — a word which needs no further comment as a term of dismissal.

'Modem' in a case like this carries with it an implication of cowardice. The modern person is afraid to do the thing properly; afraid of falling into self-parody — that is, of doing it too completely. He has to supply the inverted commas in what the Romantic would consider a caddishly un- subtle manner, just to prove to the onlook- ers that he is, at root, one of them; that he too knows that one does not really do these things these days.

The Romantic is not one of them, and she (or he) does really do these things — and what are 'these days' anyway? One does not believe one has heard of them. The two keynotes of modern dressing are casualness and individuality. Even when these are not enforced too rigidly, it is de rigueur that the modem dresser should look at ease and himself. Neither of these things is much admired by the Romantic. The phrase 'natural and unaffected' is often used by Romantics to mean that someone is modem and boring. A Romantic should be affected and not too natural. This is not to say that she lacks ease or confidence; on the contrary, a Romantic is one to whom affectation comes naturally.

The Romantic would never, of course, wear Victorian or any other underwear as outerwear. It would be far too modem and predictably eccentric. 'Neurotic' is a word she might use for this type of dres- sing, meaning that it springs from the fragmented and unregulated consciousness of the modern world. Put these out-of- place garments together with the aforementioned workman's boots and the Romantic feels as if she is witnessing a chaotic dream. So, come to that, does the modernist, but the modernist, having been through surrealism and psychedelia, finds chaotic dreams exciting and clever, while the Romantic looks on them with an unashamedly pre-Freudian mind and finds them sinister. When the Romantic calls the modern world 'mad' she is not using a figure of speech.

To understand the Romantic, one must realise that she is never eccentric — not, at any rate, in the sense of breaking with any fundamental convention. She appears to the outside world to be eccentric, and if she had any respect for the outside world that might trouble her, but the outside world (`the natives') does not consist of People Who Count. She appears to flout all sorts of conventions, but in fact she never flouts the conventions that matter. When she wears a crinoline ball-dress with a high collar and bobbed hair, she is not being odd. She is following an accepted style which has been in vogue for several years (fashions change at a more 19th-century pace in the Romantic world).

In dress, the Sloane Ranger or the Young Fogey tries to express conventional and traditional values from within the constraints of the compulsory individualism and pseudo-eccentricity of modern culture.

The Romantic, conversely, expresses her individuality, and even her eccentricity if she is genuinely eccentric, from within the formal constraints of Romantic conven- tion.

This brings us on to the Romantic attitude toward social class. Romantics do not necessarily share the same views on everything, but their attitude to this sub- ject is pretty consistent. To begin with, they are much less coy about class than almost any other group of Englist! people. They make no bones about the fact that the Classless Society — whether socialist or Thatcherite — is a bad thing. Indeed, this is probably the root cause of their distaste for both socialism and Thatcherism and, indeed, post-war politics as a whole.

The distinctions between social classes are one of the foundations of civilisation.

The decline of domestic service, social deference and what the Romantic satirist Sparrowhawk has called 'natural, organic hierarchies' has been a de-civilising influ- ence upon every class of society.

The ideal Romantic ménage includes a number of voluntary bonded servants who are looked after and protected in return for their service in a quite feudal manner, thus making the household a microcosm of the ideal Romantic-Feudal state.

Few Romantics are actually of lower- class origins and those who are are either servants of some sort or have improved themselves beyond all recognition and probably rewritten their history. Curious- ly, Romantics do not object to either of these things. If some one is clever, amusing and un-modern, dresses correctly and speaks correctly they have usually no desire to enquire into humble social origins.

Conversely, the Romantic is not neces- sarily impressed with high birth. This does not mean that she does not respect breed- ing and ancient lineage. She does — perhaps with a more genuine, mediwval sort of respect than most people today — but she also has an almost oriental con- sciousness of the possibility of loss of caste. She does not necessarily regard the mod- A Romantic ern scion a the ancient family as a fit and true representative of the Tradition. Kind hearts may not be more than coronets; but coronets without sound traditional values and attitudes do not make People Who Count.

Romantics have great confidence. Some, of course, are shy, and to be brash or strident is considered modern and un- pleasant. Nonetheless, the Romantic is usually possessed of a quiet confidence. Most Romantics have been Romantic with- out using that word since early teens at least, and to be able to pose the question: 'Is the world around me wrong and am I right?' and to answer calmly 'Yes' takes a certain degree of confidence. Membership of Romantic society increases this natural confidence considerably.

Romantic society encourages the flower- ing of the individual. Romantics enjoy other Romantics being flamboyant, they watch with appreciation as one develops new affectations. They expect one to im- prove one's 'performance'. 'All the world's a stage', said one Romantic, tut it helps to have a decent house.' The modern world, with its instinctive dislike of anything larger than itself (which includes most things), makes a very poor house.

Romantics are renowned for the curious flights of whimsy in which they indulge (whimsy is a Romantic word for fantasy. The latter term is seldom employed, being somewhat soiled by modern usage.) Some write stories, usually for private circulation among themselves only (though some are now seeing the light of publication in the Romantic and the English Magazine) and the barrier between these stories and real life is often alarmingly thin. They put each other into their stories under their real names and their pseudonyms (Romantics often have several pseudonyms). They become each other. They tell extraordinary tall stories about themselves and their friends and sometimes the tallest turn out to be true. People often think tales of Romantics wearing crinoline day-dresses in the streets or having unpaid bonded ser- vants are tall tales, for example, but both are true and, indeed, quite common.

Despite this cavalier attitude toward factual truth, Romantics regard themselves as both honest and honourable (the latter word is perhaps a Romantic monopoly these days). They despise lying for mean personal advantage and regard their word as sacred. A Romantic will not give a promise lightly, and when given it will be kept under any circumstances. Romantics will transact serious business among them- selves on an oral agreement. When Miss Hester St John heard, some months after the event, of the end of the real Stock Exchange (an event which is regarded by Romantics as a milestone in the Decline of the West and which was the last nail in the coffin of any sneaking affection which their anti-socialist instincts might have given them toward neo-capitalism) she proposed at a dinner that the motto Dictum meum pactum should pass to the Romantics.

The sacredness of one's word is one important .reason for the Romantic dislike of divorce. If one cannot keep a promise solemnly pledged before God and the congregation, then what kind of a person is one? There is a certain leniency toward things that have taken place before one became a Romantic because everyone knows that the modern world is a jungle, but marriages contracted within Society (i.e. Romantic society) are for life.

As a Romantic man recently remarked: 'Ultimately, one's word is the only thing one really has.'

Romantics tend to be apolitical as far as practical modern politics go because, as Sparrowhawk put it: 'The entire spectrum of modern politics is so far removed from anything one believes in that one cannot take sides in its battles without compromis- ing one own point of view.' Some Roman- tics, of course, are just apolitical. None would be likely to vote in an election.

Some Romantics feel that in living the life they do they are preparing the way for a gentle transition to a civilised future. They believe that the time has not come for any sort of action even if they were inclined to take it, but that the real changes in the world's history begin in the hearts and minds of men (and girls). By saying the things that no one else is saying, and practising those things in their lives, they are the first breeze of a necessary and inevitable change which will come upon the cultural climate of the world.

Many Romantics, of course, do not think anything so grandiose. They just enjoy having a jolly time and staying, as far as possible, out of the rain of modern vulgarity; but most Romantics believe, in their heart of hearts, that they are fun- damentally right and that history, in the end, must be on their side.

Previous page

Previous page