A PROSPECT OF WHITBY

Roy Kerridge visits

a town of fossils and folk memories

WHITBY Museum in Yorkshire, set in a hillside park, is one of the most interesting places I have visited. I could gaze for hours at the enchanting little toys and carvings made from Whitby jet. Jet working had its heyday in the 19th century, but Kipling fans will remember the poem `Merrow Down', which tells of Phoenicians trading goods for Whitby jet in England long ago. Part of the Just So Stories, this is my favourite poem of all time, for it had a great effect on me as a small child.

Also in Whitby Museum is a 'hand of glory', celebrated in verse and by a macabre picture in The Ingoldsby Legends, later favourites of mine. The hand is a real one, cut off a famous robber after he was hanged. Now brown and withered, it has a rough candle holder inserted. Burglars once believed that, by sympathetic magic, the robber's hand would make every door open and everyone in the house fall into a deep sleep. Whitby's hand was discovered in the rafters of a local house where a burglar must once have stayed.

William Scoresby of Whitby and his son were both Georgian whaling captains who ventured far into the iceberg-haunted seas of the Antarctic. A corner of the museum is reserved for their many trophies, and best of all, for their delightful drawings of South Polar fishes and animals.

Much of the museum is devoted to fossils found in Whitby's cliffs and beaches. The town is noted for its fossil ammonites, which resemble big, grey, curly snail shells.

Down the hill from the museum, in my sidestreet boarding house, were many other fossils. I am not referring to the lodgers, I should explain, for there was only one apart from myself. He was quite a young man who worked as a potash miner. Out on the moors, he told me, the potash mines had been tunnelled a mile below the earth's surface. Here this intrepid man worked, digging and hacking out supplies for the soapmaking and chemical indus- tries. On the mantelpiece, beside photo- graphs of the landlady's `grandbairns', were glittering unusual stones he had found, as well as many fossil ammonites in good condition. One large ammonite was in use as a door-prop. He had found the fossils on the beaches, and the stones below the ground. I couldn't help wonder- ing if they were not more valuable than he and his landlady supposed.

Like every other little house in Whitby, my boarding house always seemed to have a good coal fire buring in the grate. This was very welcome after bus rides into the moors to the south of the town, where all Yorkshire seemed covered with a cold, thick blanket of white fog.

Walking near Pickering, where the moors ended, all I could see from the path were the black tops of trees standing trunkless in the air, in a cotton wool landscape of blank whiteness. At closer range I could see the black trunks dripping with a million droplets. Certain of being stranded, I trudged despairingly between the hedges of a fog-filled country lane, when miraculously the yellow lights of a slow moving bus appeared, going all the way to Whitby.

Halfway across the moors, when night had fallen, I saw a long curve of fire against empty blackness, the flames leaping high, yellow and orange. The bus driver said that the farmers were burning the hedges. In such damp surroundings, I suppose the blaze could not spread. It was a most eerie sight. Perhaps the farmers were unwitting- ly continuing a pagan winter custom of the kind that elsewhere evolved into the blaz- ing Yule Log.

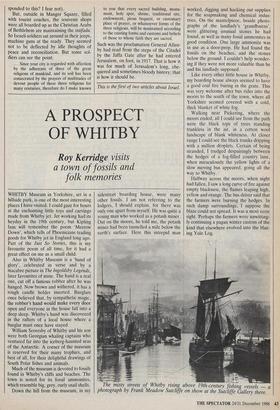

The misty streets of Whitby risin photograph by Frank Meadow Sutch above 19th-century fishing vessels — a e on show at the Sutcliffe Gallery there.

Previous page

Previous page