My table thou hast furnished

David Ekserdjian

THE ALTARPIECE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY by Jacob Burckhardt edited by Peter Humfrey

Phaidon, £75, pp.240 Peter Humfrey could probably sell sand to a sheik. Anyone who can inspire a publisher to produce such a gorgeously and lavishly illustrated translation of an ex- tended essay published nearly a century ago must have uncommon powers of per- suasion. In the event, Burckhardt's text does not require special pleading in the form of a glossy package, but one cannot help wondering if Dr Humfrey's consider- able talents are not being wasted at the University of Saint Andrews.

Although Burckhardt's collected works run to 14 volumes, it is for his masterly Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy of 1850 that he is chiefly — and rightly — remembered. Sadly, he never wrote the companion volume on art that he regarded as its essential complement. Instead, we have a study of the architecture of the period, of which there exists a recent English translation, and three essays on Collectors, Portraits, and Altarpieces. This book is an almost invariably accurate annotated edition of the last.

Burckhardt wrote from memory in Switzerland without the resources of a modern photographic or slide library. In- evitably, his choice of examples both in painting and in sculpture reflects the tastes of his age, as well as his particular affection for the art of northern Italy. Francia, Garofalo, and Gaudenzio Ferrari all loom large here, whereas Parmigianino and Pon- tormo are virtually ignored, and Andrea del Sart° is condemned for his lack of spiritual feeling. Predictably, Raphael re- presents the supreme pinnacle of art.

The period feel is even more apparent when it comes to matters of connois- seurship. We owe so much to the often despised lists compiled by Berenson that we tend to forget just how difficult even the most obvious attributions had some- times previously proved. For the great Burckhardt, Piero della Francesca's cele- brated altarpiece in the Brera was by the obscure Fra Carnevale. Now any student would recognise its correct authorship at a glance. Fortunately, Burckhardt's essay is much more than a fascinating episode in the history of taste. On the larger issues he remains exceptionally interesting, at times to such an extent that the lack of subse- quent progress is almost embarrassing. By discussing the altarpieces in terms of `Auf- gaben' (here translated as 'tasks' or 'chal- lenges), he succeeds in giving his subject a shape, and scrupulously ensures that like is compared with like. Burckhardt's original German is not broken up into chapters, but Humfrey's decision to provide headings is a wise one. The 21 divisions also serve to clarify the fact that Burckhardt categorises the altarpiece in two different ways, name- ly in terms of its format (`The Survival of the Polyptych in the Renaissance') and in terms of its subject-matter (`Scenes from the Lives of the Saints'). This pigeon- holing is occasionally over-neat, but the overall effect is generally illuminating, and incomparably preferable to an aimless chronological survey.

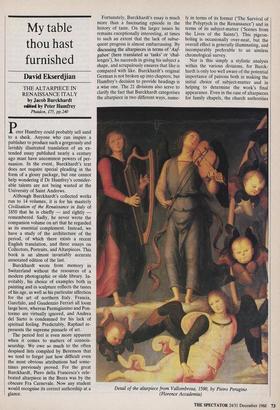

Nor is this simply a stylistic analysis within the various divisions, for Burck- hardt is only too well aware of the potential importance of patrons both in making the initial choice of subject-matter and in helping to determine the work's final appearance. Even in the case of altarpieces for family chapels, the church authorities Detail of the altarpiece from Vallombrosa, 1500, by Pietro Perugino (Florence Accademia) were frequently involved, and Burck- hardt's understanding of the significance of relics in this context has still not been universally recognised. Some modern cri- tics will no doubt dislike Burckhardt's willingness at times like this to go beyond what he can document, but that is one of his great strengths. He has the courage to risk saying things that may ultimately prove to be wrong.

Previous page

Previous page