ARTS

The Sistine Chapel

Restoring the light

Juliet Reynolds

To the Vatican!' I burst out breath- lessly as I fell into a yellow Roman taxi early one morning last September. 'Are you in a hurry to go and pray?' queried my driver with amusement, or do you have a meeting with the Pope? He's always in a hurry himself, so you may have trouble catching him. But don't worry, I'll get you there in ten minutes.' Relieved by his good-natured assurances, I explained that the cause of my haste was neither prayer nor the pontiff, but an appointment with a Vatican Museums official who would escort me to the Sistine Chapel before the hordes of tourists descended, for which purpose the utmost punctuality had been urged upon me. 'Just think,' continued my driver rather ruefully, 'in all my years I've never been to the Vatican Museums, have never seen Michelangelo's frescoes.' But did he know anything of the storm that had been raging on and off for the past several years over the cleaning of these frescoes, I inquired. Yes, he had vaguely read some- thing in his newspaper about 'explosive new colours, and that some people are saying the Vatican is destroying the fres- coes, while others say the real Michelange- lo is appearing. Of course I don't under- stand these things,' he confessed un- ashamed. 'Such arguments are only for the scholars. But if you ask me, the Vatican must be right. They're too shrewd to make a mess of things.'

As soon as he spoke, the words 'Messing with the Master, Making the Sistine Pris- tine' ran across my mind. It was the title of an article I had read only the day before while researching the Sistine Chapel clean- ing in the Vatican Museums Archive. Here I had discovered that since 1981, when Maestro Gianluigi Colalucci and his team of restorers had begun their onerous task, a veritable flood of activities had already flowed under, on and over their bridge, four years before the project is due for completion. The most noteworthy of such activities include: the shooting of nearly 40 hours of film on the various stages of the cleaning by the Nippon Television Cor- poration of Japan, the project's sponsor; the publication of three books, two of them in favour of the cleaning and the other (published, perhaps significantly, by the House of Usher in Florence) strongly opposed to it; the holding of two political debates on the subject, one in the Italian Chamber of Deputies, the other in the European Parliament in Strasbourg; the organising of hundreds of lectures and conferences by the Vatican in Italy and abroad so that the international art com- munity might be kept au fait with the project's progress; the writing of umpteen letters to the Pope by various artists and scholars requesting him to halt the project, none of which has ever been answered; and the installation of special carpets at the entrance to the Sistine Chapel so that all polluting elements may be removed from tourists' soles.

The polemics of this politically charged affair have remained essentially the same sine 's/he early years of the project. Those again it claim that Agent AB-57, the solvent used to remove the blackened layer of resinous grease and animal glue from the frescoes, is also removing a dark layer applied a secco (dry) by Michelangelo for the purpose of toning down the excessively bright colours with which he first painted the frescoes. In order to support this view, they claim that the strident, disbalanced colours of the cleaned frescoes are totally out of keeping with Michelangelo's palette and they accuse those who accept these colours as authentic of being influenced by modern visual phenomena such as colour television and photography. The restorers and their supporters counter their oppo- nents by providing powerful evidence that the luminous, often violent and dissonant colours of the cleaned frescoes are perfect- ly in keeping with other paintings by Michelangelo as well as with the colours normally used in fresco painting by the Florentine masters of that age. Moreover, they have frequently demonstrated (their bridge has been open to their critics from the beginning of the battle) that before application with AB-57 each tiny part of the painting is rigorously examined by the most scientific and accurate methods (in- cluding computer data) and that any secco applications are identified and treated with fixatives and non-water based solvents so as not to remove them. They further demonstrate that in the process of cleaning they leave a very thin patina of the glue/dirt layer on the painting so that the danger of wiping out Michelangelo, either a fresco or a secco, is entirely eliminated.

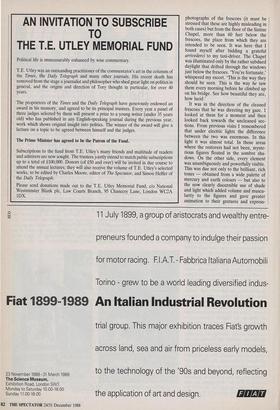

Yet however much the opposition may rant and rave against the restorers, and however frequently the latter may patient- ly counter their charges, the proof of the cleaning is in the seeing. By this I mean seeing not from `before' and 'after' colour Part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling before and after restoration: Photo Vatican Museums — courtesy of NTV Tokyo

photographs of the frescoes (it must be stressed that these are highly misleading in both cases) but from the floor of the Sistine Chapel, more than 60 feet below the frescoes, the place from which they are intended to be seen. It was here that I found myself after bidding a grateful arrivederci to my taxi-driver. The Chapel was illuminated only by the rather subdued daylight that drifted through the windows just below the frescoes. 'You're fortunate,' whispered my escort. 'This is the way they should be seen. This is the way he saw them every morning before he climbed up on his bridge. See how beautiful they are, how lucid.'

It was in the direction of the cleaned frescoes that he was directing my gaze. I looked at them for a moment and then looked back towards the uncleaned sec- tions. From previous visits I remembered that under electric lights the difference between the two was enormous. In this light it was almost total. In those areas where the restorers had not been, myste- rious figures floated in the sombre sha- dows. On the other side, every element was unambiguously and powerfully visible. This was due not only to the brilliant, rich tones — obtained from a wide palette of mercury and earth colours — but also to the now clearly discernible use of shade and light which added volume and muscu- larity to the figures and gave greater animation to their gestures and express- ions. Also now crystal clear was the artist's highly inventive architectural design painted to divide scene from scene, figure from figure, and which held the ceiling firmly together as a grand, sweeping, unified whole.

Casting my eyes in head-spinning admiration across this majestic vision, I remembered that Michelangelo's contem- porary Giorgio Vasari had written of the ceiling's 'restoring light to a world that for centuries had been plunged into darkness'. Was it possible that Vasari was referring to the obscure, subtle Michelangelo so pre- cious to the members of the opposition, or was he referring to the bold, fiery Michel- angelo of the vivid, luminous palette? Standing there, looking from one Michel- angelo to the other, common sense told me there could be no doubt, and I understood why one supporter had said of this cleaning that it is 'restoring light to a work of art that for centuries has been shrouded in a layer of darkness'.

Previous page

Previous page