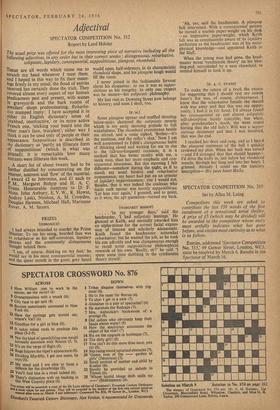

Adjectival

The usual prize was offered for the most interesting piece of narrative including all the following adjectives, in any order but in their correct sens'es : disingenuous, rebarbative. solipsistic, lapidary. consequential, supposititious, plangent, rhomboid.

THESE are all words which cause me to scratch my head whenever I meet them, and I hoped in this way to fix their mean- ings firmly in my mind; the flood of entries received has certainly done the trick. They covered almost every aspect of our human predicament past and present, with scenes In graveyards and the back rooms of Jewellers' shops predominating. Rebarba- IlYe stumped many : I have accepted it in Faller its English dictionary sense of crabbed, unattractive,' or its more active French one, 'sticking your beard into the Other man's face, truculent'; either way I think it can be used only of people or their appearance. Suppositious is described in fly dictionary as 'partly an illiterate form Of supposititious' (which is what was Printed); it is remarkable how many entrants were illiterate this week.

A short list of about twenty had to be further distilled by concentrating on the Interest, neatness and 'flow' of the material. I award £2 to Jebronius, and £1 each to

M., Margaret Bishop and H. A. C. Moss, Honourable mentions to D. F. Moss, John Astbury, E. V. W., R. Howat, Audrey Laski, Nimbus, A. M. Crowden, bouglas Hawson, Michael Hall, Marianne Rover, A. M. Sayers.

PRIZES

(IEBRONIUS)

Minister. had always intended to murder the Prime Minister. To me his smug, bearded face was

as rebarbative as his self-conscious, lapidary Phrases and the consistently disingenuous thought behind them.

I am, of course, thinking on my feet,' he Would say in his most consequential manner;

and the queer mouth in the great, grey beard

would open, half-sideways, in its characteristic rhomboid shape, and his plangent laugh would fill the room.

I never joined in the fashionable fervour about his eloquence: to me it was as suppo- sititious as his integrity. In only one respect was he sincere—his solipsistic philosophy.

My last visit to Downing Street now belongs to history; and soon I shall, too.

(P. tq.)

Some plangent uproar and muffled shouting below-stairs shattered the solipsistic reverie which is my early morning prelude to full wakefulness. The rhomboid prominence beside me stirred, and a voice sighed, 'Bother—it's the coalman, and the cellar's shut.' Now 1 am well accustomed to Edith's disingenuous habit of thinking aloud and waiting for me to rise to the (all-too-frequent) occasions it is a method that has better results with me, a meek man, than her more emphatic and con- sequential utterances. But this morning I felt different—somehow during the night, as if to match my usual hirsirte and rebarbative countenance, my heart had put on an armour of lapidary imperviousness : rise I would not. Besides, that it was indeed the coalman who made such uproar was merely supposititious. `Let him roar again,' I grunted, and to point, as it were, the apt quotation—turned my back.

(MARGARET BISHOP)

'In my younger days,' said the headmaster, 'I had solipsistic leanings' He glanced at Keith, and mentally awarded him an alpha-minus for the correct facial expres- sion of interest and scholarly amusement. Keith found the headmaster somewhat rebarbative; but he wanted the job, so he took his cue adroitly and was disingenuous enough to recall some supposititious philosophical research of his own. 'Really, sir7' he said. 'I spent some time dabbling in the syndianetic theory myself.' 'Ala, yes, said the headmaster. A plangent bell intervened. With a consequential gesture he moved a marble paper-weight on his desk —an impressive paper-weight, which Keith felt was as complacently aware of its lapidary perfection as the headmaster was of his meta- physical knowledge—and appointed Keith to the Staff.

When the young man had gone, the head- master wrote `syndianetic theory' on his blot- ting-pad, surrounded by a neat rhomboid, to remind himself to look it up.

(H. A. C. EVANS)

To make the return of a book the excuse for suggesting that I should visit my cousin Janet's flat was, of course, disingenuous. I knew that the rebarbative female she shared with was away and that this was my oppor- tunity. I had it in for Janet. I'd always found her consequential air and almost solipsistic self-absorption barely tolerable; but when, after grandmother's death, she went round hinting that the old lady's Will was a suppo- sititious document and that 1 was involved, that was the end.

I reached her door and rang, and as I heard the plangent summons of the bell I quickly reviewed my plan. When her back was turned —and I'd arranged that that should happen— I'd drive the knife in, just below her rhomboid muscle, through her lung and into her heart. I grinned. Already I could see the lapidary inscription— Hic jacet Janet Hicks.

Previous page

Previous page