A CUBAN HEEL

Anthony Daniels on

the inflated hero of a nation

ON THE 137th anniversary of the birth of Cuba's 'heroe nacional', Jose Marti, the official organ of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, Bastion, carried a quotation from his works printed in bold lettering:

Two useful truths for Our America: the crude, unequal and decadent character of the United States, and the continued existence' there of all the violence, discord, immorality and disorder of which the Spanish-American peoples are accused.

Actually, it doesn't take long in Cuba before one learns thoroughly to detest the national hero. This has less to do with the man himself than with the use to which he has been put — the cheap busts of him for sale in otherwise empty shops, the prepost- erously orotund speeches that four- and five-year-olds are trained to make before his memorials throughout the country, the little quotations that adorn the walls of post offices (`To create is to be victorious'), art galleries ('Art is life itself. Art knows nothing of death'), and the crumbling streets (Wen come in two types: those who

love and construct, and those who hate and destroy'). Every school has a shrine to him, there is an institute, Estudios Martianos, and his complete works are for sale in every bookshop, alongside Brezhnev's memoirs, the speeches of Konstantin Cher- nenko and Todor Zhivkov, an anthology called Bulgarian Journalists on the Path of Leninism, El joven Erich, The Young Erich (Honecker, of course), and, most touching of all, a book for children entitled Felix significa feliz, Felix Means Happy, the Felix of the title being Dzherzhinsky, the first head of the Soviet secret police who managed in a few years to kill vastly more political prisoners than Tsarism man- aged in a century. One doesn't know whether to laugh or cry.

Marti has two main uses. The first is his anti-Americanism. His attitude to the Col- ossus of the North was actually more subtle than the present propaganda allows, but his writings are nonetheless a rich source of disparagement. The contrast between the poetic, refined, spiritual but impoverished south (Nuestra America, Our America)

and the crass, vulgar, materialistic but rich north (Their America) is one to which he drew attention time and again, in common with other Latin American intellectuals of the time, such as the Nicaraguan poet Ruben Dario and the Uruguayan critic Rodo. This emotionally rewarding but intellectually debilitating comparison, to which proud but politically impotent peo- ples have often resorted when faced with a materially superior culture, has been in- corporated as an article of faith into the state religion of Cuba, and is repeated ad nauseam. Its noble purpose is to promote hatred and contempt as well as self- satisfaction.

I bought a short book in Havana called Estados Unidos, la otra cara (The Other Face of the United States), by Cuba's ambassador to the United Nations. Dedi- cated `to the Indians, to the blacks, to the hispanics, to the homeless, to the poor in North America and to all those who suffer in their own flesh the violation of human rights', it also employs Marti's 'two useful truths' as an epigraph. The burden of the book's denunciation is precisely the same as that of Marti a hundred years earlier, without any intellectual development whatsoever: that amidst the wealth of the United States there is squalor, that free- dom there belongs only to the strong. Every possible discreditable fact is gar- nered (from the American press, of course) to prove that the Monster, as Marti called the country, 'knows only how to suck blood'. Why so odious a country should have attracted tens of millions of immigrants, and why its culture should have so fascinated the world, are not, needless to say, questions fully dealt with in the book. Such truths as it contains are adduced in the service of a Big Lie, and even the title of the book suggests a lie: since rio other face of the United States than the one presented in the book — of racial discrimination, poverty, crime, por- nography and drug addiction — is ever presented to the Cuban public by the omnicompetent authorities.

In a Sunday edition of the newspaper Juventud Rebelde (Rebel Youth — the very name is mendacious, as any youth who had the temerity to rebel would soon discover) there was an interesting account by a Cuban journalist of a journey to the northern border of Mexico, the purpose of which was, of course, to examine the baleful effects of proximity to Sodom and Gomorrah. En route he met some Mexican journalists, and they communed about their financial problems: ... I learnt, in conversations begun in the editorial offices of newspapers and finished in bars.., that this flack of money] was a problem common to all the journalists of the continent. Very few were the journalists of the area who had sufficient income to pay for an investigation into a foreign country. Only the gringos and Europeans — alleged a respected colleague — had enough money to travel through our countries to write about

realities they didn't understand. With us, talent is synonymous with little money.

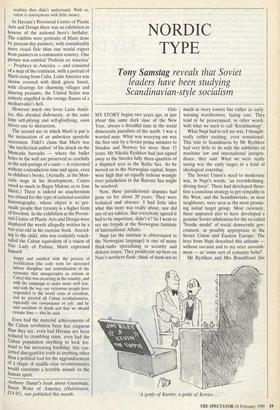

In Havana's Provincial Centre of Plastic Arts and Design there was an exhibition in honour of the national hero's birthday. The exhibits were portraits of Marti done by present-day painters, with considerably more visual flair than one would expect from painters in a communist country. One picture was entitled 'Profecia en America' — Prophecy in America — and consisted of a map of the continent, with a portrait of Marti rising from Cuba. Latin America was Shown covered with thick green forest, With clearings for charming villages and dancing peasants; the United States was entirely engulfed in the orange flames of a mediaevalist's hell.

However much one loves Latin Amer- ica, this abysmal dishonesty, at the same time self-pitying and self-glorifying, soon drives one to distraction.

,The second use to which Marti is put is the insinuation of an unbroken apostolic succession. Fidel's claim that Marti was 'the intellectual author' of his attack on the Moncada barracks — where the bullet holes in the wall are preserved as carefully as the nail-parings of a saint — is reiterated Without contradiction time and again, even in children's books. (Actually, at the Mon- cada stage in his development, Castro owed as much to Bugsy Malone as to Jose Marti.) There is indeed no anachronism too absurd for this type of national-socialist historiography, whose object is to per- suade people that tyranny is a higher form of freedom. In the exhibition at the Provin- cial Centre of Plastic Arts and Design were displayed the words allegedly written by a ten-year-old in his exercise book. Accord- ing to the child, who was evidently vouch- safed the Cuban equivalent of a vision of Our Lady of Fatima, Marti expressed himself happy and satisfied with the process of rectification [the code term for increased labour discipline and centralisation of the economy that masquerades as reform in Cuba] that was occurring in the country, and with the campaign to make more with less, and with the way our victorious people have responded to the world crisis of socialism, and he greeted all Cuban revolutionaries, especially our comandante en jefe, and he said socialism or death and that we should remain firm — this he said.

Even had the material achievements of the Cuban revolution been less exiguous than they are, even had Havana not been reduced to crumbling ruins, even had the Cuban population anything to look for- ward to but increasing hardship, this con- certed disregard for truth as anything other than a political tool for the aggrandisement of a clique of middle-class revolutionaries would constitute a horrible assault on the human spirit.

Anthony Daniel's book about Guatemala, Sweet Waist of America (Hutchinson, £14.95), was published this month.

Previous page

Previous page