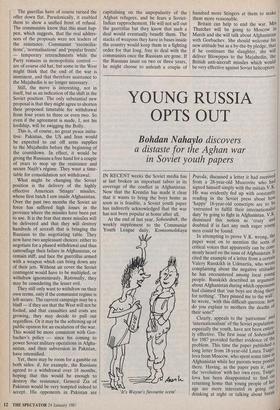

ODDS AGAINST AN AFGHAN PEACE

Radek Sikorski on the

snags in the Soviet-backed amnesty proposals

I TOOK a bet with a Social Democratic peer before the recent hullabaloo that by next Christmas there will still be Russian soldiers in Afghanistan. Needless to say I will gladly lose a bottle of Bollinger if that means the end of suffering for the Afghans. His lordship is probably already licking his lips but I am not rushing to Oddbins yet. Major-General Najibullah announced last week that the Afghan army and the Soviet contingent 'suspended combat op- erations'. There will be a general amnesty and Islam is to be the national religion of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. The leaders of the resistance are invited to negotiations and might be allowed to join a Government of National Unity. It is hinted that if the Mujahedin respond favourably the Russians might consider withdrawing in the near future.

General Najib's offer of an amnesty should be welcomed. His regime is one of the nastiest in the world today. First as a security police chief, and now as the Communist Party first secretary, he is personally responsible for 'widespread' and 'systematic' torture of political prison- ers, to quote the recent Amnesty Interna- tional report. Freeing the thousands of victims from the notorious Pul-i-charki prison could become a tangible proof of his intentions. But his amnesty is only to apply to deserters from the Afghan army. Those who redefect will not be punished. The embassy spokesman clarified that of the `few' political prisoners that there are, only those who renounce counter-revolution will be released. In other words the regime will not release its opponents, but only those who have been broken by the harsh conditions and torture, or blackmailed into collaboration.

There are a couple of other snags about the proposals. As everybody who has read Flashman knows, the Afghan winter is savage, so there is no fighting now anyway — most passes are blocked by snow and it is too cold for the soldiers to ramble the mountains.

The army is to confine itself to its permanent .postings and to 'guarding the borders'. If the Mujahedin continue to supply their bases from Pakistan and Iran, the ceasefire will be revoked. But sealing the borders is precisely what the Afghan and Soviet armies have in vain tried to do for seven years. If the offer is conditional on the Mujahedin voluntarily starving themselves of supplies, while the govern- ment can safely hold on to the positions which have been under their constant harassment, then the advantages may seem less than reciprocal.

What of the pledge to make Islam the national religion? As they say in Poland: the devil got dressed up in a cassock and is ringing the altar bell with his tail. In wartime desperation, Stalin too allowed orthodox services and exhorted the Red Army soldiers to fight Hitler for Mother Russia. But the Afghans know the practic- al value of constitutional guarantees of religious freedoms north of the border. This regime, together with the Soviet army, has destroyed Herat, the Lourdes of central Asia, and hundreds of mosques, religious colleges and shrines. This offer is not likely to be taken seriously.

But maybe an agreement could be reached through negotiations? The com- munists are offering safe passage to any `bandit' leader who wishes to come to talk to them; the proclamations say that 417 groups numbering 37,000 members have already come forward. (This is an absurd figure only days after the offer was made, but by the government's own admission it suggests the scale of popular resistance.) What is proposed, however, is not that leaders such as Masud, Rabbani, Khalis, Gailani or Hekmatyar, sit down at a table with Dr Najib and after a good deal of tough talk iron out a historic compromise. No, the men who command tens of thousands of guerillas, have thousands of bases all over the country, and are better equipped than ever, are expected to join the National Fatherland Front, and make submissions to what they regard as a Quisling regime. To take part in the National Unity Government the counter- revolutionaries (`misled brothers' since last week) would have to accept the irreversi- bility of the revolution and the leadership of the Communist Party. The guerillas have of course turned the offer down flat. Paradoxically, it enabled them to show a unified front of refusal. The communists know that this must hap- pen, which suggests, that the real addres- sees of the proposals were not leaders of the resistance. Communist 'reconcilia- tions', `normalisations' and 'popular fronts' — temporary retrenchments while the Party remains in monopolistic control are of course old hat, but some in the West might think that the end of the war is imminent, and that therefore assistance to the Mujahedin is no longer necessary.

Still, the move is interesting, not in itself, but as an indication of the shift in the Soviet position. The only substantial new proposal is that they might agree to shorten their proposed timetable for withdrawal from four years to three or even two. So even if the agreement is made, I, not his lordship, will be swigging the Bolly.

This is, of course, no great peace initia- tive: Pakistan, the US and Iran would be expected to cut off arms supplies to the Mujahedin before the beginning of the countdown. In effect, it would be giving the Russians a free hand for a couple of years to mop up the resistance and secure Najib's regime. They want a time- table for consolidation not withdrawal.

What might be changing the Soviet position is the delivery of the highly effective American `Stinger' missiles, whose first batch I saw inside Afghanistan. Over the past two months the Soviet air force has suffered high losses in the province where the missiles have been put to use. It is the fear that more missiles will be delivered and that they will destroy hundreds of aircraft that is bringing the Russians to the negotiating table. They now have two unpleasant choices: either to negotiate for a phased withdrawal and thus camouflage their failure in Afghanistan, or remain stiff, and face the guerrillas armed with a weapon which can bring down any of their jets. Without air cover the Soviet contingent would have to be multipled, or withdraw ignominiously. Rationally, they may be considering the lesser evil.

They still only want to withdraw on their own terms, only if the communist regime is left secure. The current campaign may be a bluff — if they see that the West will not be fooled, and that casualties and costs are growing, they may decide to pull out regardless. Or it may be the softening up of public opinion for an escalation of the war. This would be more consistent with Gor- bachev's policy — since his coming to power Soviet military operations in Afgha- nistan, and their subversion in Pakistan, have intensified.

Yet, there may be room for a gamble on both sides: if, for example, the Russians agreed to a withdrawal over 18 months, hoping that this would be enough to destroy the resistance, General Zia of Pakistan would be very tempted indeed to accept. His opponents in Pakistan are capitalising on the unpopularity of the Afghan refugees, and he fears a Soviet- Indian rapprochement. He will not sell out the guerrillas but they know that such a deal would eventually benefit them. The stacks of weapons they have in bases inside the country would keep them in a fighting order for that long, free to deal with the communists once the Russians are gone. If the Russians insist on two or three years, he might choose to unleash a couple of hundred more Stingers at them to make them more reasonable.

Britain can help to end the war. Mrs Thatcher will be going to Moscow in March and she will talk about Afghanistan with Gorbachev. She should welcome his new attitude but as a by-the-by pledge, that if he continues the slaughter, she Will deliver Blowpipes to the Mujahedin, the British anti-aircraft missiles which would be very effective against Soviet helicopters.

Previous page

Previous page