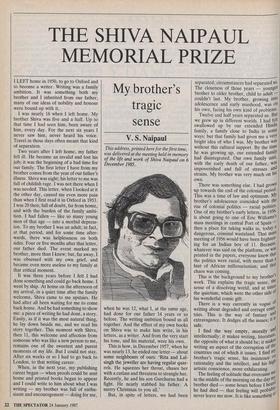

THE SHIVA NAIPAUL MEMORIAL PRIZE

I LEFT home in 1950, to go to Oxford and to become a writer. Writing was a family ambition. It was something both my brother and I inherited from our father; many of our ideas of nobility and honour were bound up with it.

I was nearly 18 when I left home. My brother Shiva was five and a half. Up to that time I had seen him, been aware of him, every day. For the next six years I never saw him, never heard his voice. Travel in those days often meant that kind of separation.

Two years after I left home, my father fell ill. He became an invalid and lost his job; it was the beginning of a bad time for our family. The first letter I have from my brother comes from the year of our father's illness. Shiva was eight; his letter to me was full of childish rage. I was not there when I was needed. This letter, when I looked at it the other day, caused me even more pain than when I first read it in Oxford in 1953. I was 20 then; full of doubt, far from home, and with the burden of the family ambi- tion, I had fallen — like so many young men of that age — into a morbid depress- ion. To my brother I was an adult; in fact, at that period, and for some time after- wards, there was helplessness on both sides. Four or five months after that letter, our father died. The event marked my brother, more than I knew; but, far away, I was obsessed with my own grief, and became even more useless to my family at that critical moment.

It was three years before I felt I had done something and could go back home. I went by ship. At home on the afternoon of my arrival, in a quiet time after the family welcome, Shiva came to me upstairs. He had after all been waiting for me to come back home. And he had something to show me: a piece of writing he had done, a story. Easily, as if it was the most natural thing, he lay down beside me, and we read his story together. This moment with Shiva, then 11, this welcome and affection from someone who was like a new person to me, remains one of the sweetest and purest moments of my life. But I could not stay. After six weeks or so I had to go back to London, to that writing career.

When, in the next year, my publishing career began — when proofs could be sent home and printed books began to appear and I could write to him about what I was writing — my brother was full of enthu- siasm and encouragement — doing for me,

My brother's tragic sense

V. S. Naipaul

This address, printed here for the first time, was delivered at the meeting held in memory of the life and work of Shiva Naipaul on 6 December 1985.

when he was 12, what I, at the same age, had done for our father 14 years or so before. The writing ambition bound us all together. And the effect of my own books on Shiva was to make him write, in his letters, as a writer. And from the very start his tone, and his material, were his own.

This is how, in December 1957, when he was nearly 13, he ended one letter — about some neighbours of ours: 'Rita and Lal- singh the jeweller are having regular quar- rels. He squeezes her throat, chases her with a cutlass and threatens to strangle her. Recently, he and his son Gurcharan had a fight. He nearly stabbed his father. A merry Christmas to you all.'

But, in spite of letters, we had been separated; circumstances had separated us. The closeness of those years — younger brother to older brother, child to adult -- couldn't last. My brother, growing int° adolescence and early manhood, was on his own, facing his own kind of problems. Twelve and half years separated us. But we grew up in different worlds. I had felt swallowed up by our extended Hindu family, a family close to India in some ways; but that family had given me a very bright idea of who I was. My brother was without this cultural support. By the time he was growing up, our extended family had disintegrated. Our own family unit, with the early death of our father, was impoverished and full of stresses and strains. My brother was very much on his own.

There was something else. I had grown 'up towards the end of the colonial period. This was a time of law and optimism. MY brother's adolescence coincided with the rise of colonial politics — racial polities. One of my brother's early letters, in 1956, is about going to one of Eric Williams's mass meetings in central Port of Spain then a place for taking walks in, today a dangerous, criminal wasteland. That mass meeting of 1956 would have been frighten' ing for an Indian boy of 11. Because' whatever was said on the platform, or was printed in the papers, everyone knew that the politics were racial, with more than a hint of African millenarianism; and that chaos was coming. This is the background to my brother's work. This explains the tragic sense, the sense of a dissolving world, and at times the quietism, which were the other side ° his wonderful comic gift. There is a way currently in vogue of writing about degraded and corrupt courlj tries. This is the way of fantasy an extravagance. It dodges all the issues; it , safe. I find the way empty, morally and intellectually; it makes writing, literature' the opposite of what it should be; it makes writing an aspect of the corruption of u," countries out of which it issues. I find 111„Y brother's tragic sense, his insistence 0" rationality and the intellect, and his bir artistic conscience, more exhilarating. e The feeling of solitude that overcame In in the middle of the morning on the day and brother died — some hours before I hear he had died — that feeling will probaul never leave me now. It is like something a the tips of my fingers; something of which I am reminded by the very act of composi- tion, the family vocation we shared. But there is his work. That revivifies. It is a large body of work and it will hold its own: the record of a growing knowledge of the world, an ever-deepening response to the world, and of a skill developing to match knowledge and response. My brother aimed high; the better he became the higher he aimed. What an instrument his prose became. And consider the aston- ishing completeness of his Jonestown book. What ;a labour he imposed on himself there, finding a narrative — which was also an analysis — to link the now congruent, now complementary, corrup- tions of black Guyana and sunny Califor- nia. He could so easily have got away with less.

His development in the last eight or nine years was prodigious. This was more or less the period of his association with the Spectator. The welcome and freedom and fellowship he found on the paper answered his need; and he flourished. The manifold elegance of the paper is not a matter of literary style alone. It is also an elegance of mind, an expression of a high civilisation.

Men cannot do more for other men than to express fellowship with them. This meeting is an expression of fellowship; it is very moving.

Previous page

Previous page