Old hat

Mark Steyn

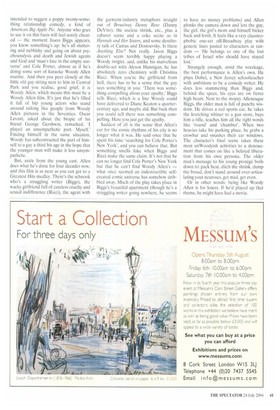

Anything Else 15, selected cmemas

T realised the other day I couldn't 1 remember the last Woody Allen movie I'd seen. I mean, I remember I've seen several in the last seven or eight years, but I've no clue what any of them were, or who was in them, or what happened — except a vague recollection of a rather creepy-looking Woody talking about French kissing. No, wait, that was his public-service announcement for the French government, when Chirac's obstructionism on Iraq alienated so many Americans that it began to have trade implications and Paris decided to launch a promotional campaign. Nothing sums up the yawning chasm between Old Europe and the United States more poignantly than the French government's touching belief that hiring Woody Allen as their pitchman was the way to appeal to Mr and Mrs America.

Drearnworks didn't make that mistake. In their trailers and posters for Anything Else there's not a glimpse of Woody. Just Jason Biggs (the endearing lug from the American Pie trilogy) and Christina Ricci (from everything) and wacky pink lettering

intended to suggest a poppy twenty-something relationship comedy, a kind of American Big Apple Pie. Anyone who goes to see it on this basis will feel sorely cheated — the moment Jason Biggs appears, you know something's up: he's all stuttering and nebbishy and going on about psychoanalysis and death and Jewish agents and God and `man's fate in the empty universe' and Cole Porter, almost as if he's doing some sort of karaoke Woody Allen routine. And then you peer closely at the little old guy sitting next to him in Central Park and you realise, good grief, it is Woody Allen, which means this must be a Woody Allen film. It's just that he's filled it full of hip young actors who stand around talking like people from Woody Allen pictures in the Seventies. Oscar Levant, asked about the biopic of his friend George Gershwin, remarked. 'I played an unsympathetic part. Myself.' Finding himself in the same situation. Woody has subcontracted the part of himself to a guy a third his age in the hope that the younger man will make it less unsympathetic.

But, aside from the young cast, Allen does what he's done for four decades now, and this film is as near as you can get to a Greatest Hits medley. There's the schnook who's a struggling writer (Biggs), the wacky girlfriend full of careless cruelty and sexual indifference (Ricci), the agent with

the garment-industry metaphors straight out of Broadway Danny Rose (Danny DeVito), the useless shrink, etc., plus a cabaret scene and a coke scene as in Hannah and Her Sisters, and some desultory talk of Camus and Dostoevsky. Is there Anything Else? Not really. Jason Biggs doesn't seem terribly happy playing a Woody twiglet, and, unlike his marvellous double-act with Alyson Hannigan, he has absolutely zero chemistry with Christina Ricci. When you're the girlfriend from hell, there has to be a sense that the guy sees something in you: 'There was something compelling about your apathy,' Biggs tells Ricci, which is a line Woody could have delivered to Diane Keaton a quartercentury ago, and maybe did. But back then you could tell there was something compelling. Here you just get the apathy.

Saddest of all is the sense that Allen's ear for the comic rhythms of his city is no longer what it was. He said once that he spent his time 'searching for Cole Porter's New York', and you can believe that. But something smells fake when Biggs and Ricci make the same claim. It's not that he can no longer find Cole Porter's New York but that he can't find Woody Allen's — what once seemed an indestructible selfcreated comic universe has somehow dribbled away. Much of the play takes place in Biggs's beautiful apartment (though he's a struggling writer going nowhere, he seems to have no money problems) and Allen plonks the camera down and lets the guy, the girl, the girl's mom and himself bicker back and forth. It feels like a very claustrophobic one-set off-Broadway play with generic lines pasted to characters at random — 'He belongs to one of the lost tribes of Israel who should have stayed lost.'

Strangely enough, amid the wreckage, the best performance is Allen's own. He plays Dobel, a New Jersey schoolteacher with ambitions to be a comedy writer. He does less stammering than Biggs and, behind the specs, his eyes are on fierce high beam. Next to the mopey Allenesque Biggs, the older man is full of punchy wisdom. He drives a red sports car, he takes the kvetching whiner to a gun store, buys him a rifle, teaches him all the right words like 'round' and 'chamber'. When two heavies take his parking place, he grabs a crowbar and smashes their car windows. The character's final scene takes these most unWoodyish activities to a denouement that comes on like a belated liberation from his own persona. The older man's message to his young protégé boils down to: pack heat, ditch the shrink, dump the broad, don't stand around over-articulating your neuroses, get mad, get even.

Or in other words: being like Woody Allen is for losers. If he'd played up that theme, he might have had a movie.

Previous page

Previous page