A newfangled and funny romp

D. J. Taylor

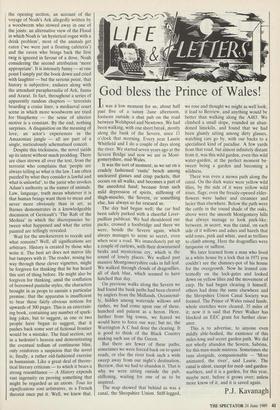

A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 101/2 CHAPTERS by Julian Barnes

Cape, £11.95, pp.309

You can already picture the judges of this year's Sunday Express fiction prize, that fine middlebrow institution, puzzling over Julian Barnes's new novel. 'But it isn't a novel', somebody will say. 'Is it supposed to be funny?', somebody else will wonder. 'Where are all the characters?', a third person will demand. 'It hasn't got a plot', all three will cry in unison. These com- plaints — and they are the usual com- plaints directed at this type of book — are almost wholly accurate. For A History of the World in 101/2 Chapters is not a novel, according to the staider definitions; it possesses no character who rises above the level of a cipher and no plot worth speak- ing of. It is sharp, funny and brilliant without suggesting that this sharpness, humour and brilliance is sufficient to carry through its purpose to any satisfactory conclusion. Yet it is a significant novel, if only because it provides an inventory of the hoops through which the contemporary novelist has to jump if he wants to be taken seriously.

The dilemma of the modern novelist is not often enough appreciated by the reader of fiction who imagines that all you have to do is invent a few characters and send them shuffling off through a more or less plausi- ble story. A skim through the latest Carey or Ackroyd might suggest that what lies at the heart of contemporary writing is arti- fice, but a better word would be self- consciousness. Any serious novelist worth his advance knows, you see, that fiction is a trick, a lie, a piece of sleight-of-hand. Consequently, there exists a whole pack of modern writers who delight in giving the game away, in telling you that they are making it up, in indulging in outrageous manipulations of character and plot. The result is that hardly anyone in these novels — brilliant novels, swimming with lively conceits — has that most necessary fiction- al quality, a life of their own.

A History is another of these newfangled romps, a series of neat, artfully stage- managed stories which combine to create a bizarre, off-centre view of world history. Most of its conventions are established in the opening section, an account of the voyage of Noah's Ark allegedly written by a woodworm who stowed away in one of the joists: an alternative view of the Flood in which Noah is 'an hysterical rogue with a drink problem', most of the animals get eaten ('we were just a floating cafeteria') and the raven who brings back the first twig is ignored in favour of a dove, Noah considering the second attribution 'more appropriate'. It is intensely funny — at one point I simply put the book down and cried with laughter — but the serious point, that history is subjective, endures along with the attendant paraphernalia of Ark, fauna and Ararat. In fact, throughout a series of apparently random chapters — terrorists boarding a cruise liner, a mediaeval court scene in which more woodworm are tried for blasphemy — the sense of ulterior motive is a constant. By the end, nothing surprises. A disquisition on the meaning of love, an actor's experiences in the Amazonian jungle — all are part of a single, meticulously schematised conceit.

Despite this tricksiness, the novel yields up its intent without much prodding. There are clues strewn all over the text, from the terrorist who complains that 'people are always telling us what is the law. I am often puzzled by what they consider is lawful and what is unlawful', to the jurist who invokes Adam's authority as the namer of animals. Law, language, truth mean whatever it is that human beings want them to mean and never more obviously than in art, as Barnes demonstrates in a knowledgeable discussion of Gericault's 'The Raft of the Medusa' in which the discrepancies be- tween what happened and what the artist painted are tellingly revealed. Wait for the smokescreen to recede and what remains? Well, all significations are arbitrary. History is created by those who write it. The best art does not mirror life but tampers with it. The reader, nosing his way through these clever vignettes, might be forgiven for thinking that he has heard this sort of thing before. He might also be forgiven for thinking, amid the conflation of borrowed pastiche styles, the characters brought in as props to sustain a particular premise, that the apparatus is insufficient to bear these fairly obvious notions for upwards of 300 pages. This is an entertain- ing book, containing any number of spark- ling jokes, but to suggest, as one or two people have begun to suggest, that it pushes back some sort of fictional frontier would be a mistake. The final section, set in a hedonist's heaven and demonstrating the eventual tedium of continuous bliss, only reinforces a suspicion that the novel is, finally, a rather old-fashioned exercise in humanism. Like a great deal of theore- tical literary criticism — to which it bears a strong resemblance — A History expends vast ingenuity on proving something that might be regarded as an axiom. Tous les significations sont arbitraires, as a French theorist once put it. Well, we knew that.

Previous page

Previous page