Exhibitions

Stephen Conroy (Marlborough Fine Art, till 29 July)

Conroy was here

Giles Auty

Ever since a display of his work in Edinburgh first attracted the attention of London dealers two years ago, the name of Conroy has seemed almost as ubiquitous in its coverage as that of Kilroy. We have learned the intimate details of his unhappy contractual relationship with a group of would-be protectors called Conservation Management on television and in the press yet, until now, have seen little to justify so much fuss made about this youthful Scot- tish artist. Now, at last, our young Lochin- var has not so much come out of, as in the West, with his first one-man exhibition at 6 Albemarle Street, Wi. As this is the London headquarters of Marlborough Fine Art you will surmise correctly that he is contracted no longer to a bunch of relative- ly powerless unknowns but to one of the Western world's major art dealers.

Clearly Conroy has been working hard while the legal and financial squabbles have been taking place elsewhere: the Marlborough exhibition comprises 49 paintings and quite a few drawings. I cannot remember so much attention being given to an artist in his early 20s since all the hullabaloo surrounding Hockney's modish tributes to Dubuffet back in the Sixties. Whatever else Conroy may be, he is not obviously modish in the manner of our Hockney of yesteryear. Perhaps con- tinuing to live near Glasgow and a degree of shyness have protected the young Scot- tish artist so far. Conroy's reputed lifestyle sounds about right for the serious young genius. I do not wish to sound carping and can understand everyone's desire to salute a youthful British master but feel a degree of caution is necessary here.

First to the paintings themselves. All are figure paintings or portraits and range from relatively straightforward studies to com- plex allegories. So far as I recollect all the figures are male, of whom a large number wear hats and/or what we think of now as National Health glasses. Again, quite a proportion of the lenses of the latter catch the light so that no eye is visible under- neath. The device is interesting, up to a point, but tends to be over-used; here we are reminded that the artist is a young man whose pictorial sophistication is not only remarkable but of pretty recent origin.

Conroy was born in 1964 and is the latest precocious talent to emerge from Glasgow School of Art where graduate and post- graduate studies occupied him from 1982 to 1987. His predecessors there include Steven Campbell, Ken Currie, Peter How- son and Adrian Wiszniewski, whose transi- tion from cubs to fully lionised status occupied but the twitching of a whisker. All four have over-produced as a result of the rapidity of their recognition and I hope the same will not happen now with Con- roy. All five young artists took part in the Edinburgh exhibition The Vigorous Im- agination two summers ago and, even then, Conroy probably generated the most active discussion. One does not need to be a trained art historian to spot the allusive nature of Conroy's present productions: Sickert and Degas are obviously exemplary in the nature of Conroy's space, colour and cropped compositions. In 'Something Spe- cial for Tea' Conroy acknowledges Sick- ert's 'Ennui' openly. One may detect fain- ter traces of Seurat, Stanley Spencer and Edward Hopper also. Hopper via Caravag- gio provides a handy potted description of the nature of some of Conroy's interiors.

All these are excellent masters, of course, and the fuss made already about Conroy reveals that painterly reaction has become respectable at last. A few weeks ago I quoted Hilton Kramer's dictum about the urgent necessity for us to 're- negotiate our pact with the past'. His words were written back in 1971, though, and I, too, have been urging a similar course from only a few years later. Yet neither of us would have expected to have been taken too literally or for the process to have taken so long. In urging students to study Veronese and Bellini rather than Schnabel and Polke, say, one had hoped to point out what was possible in paint rather than suggesting avenues for possible pas- tiche.

Conroy is a surprisingly good product of an era when standards of thinking and writing about art have rarely risen above the abysmal. He is still immature and derivative, true, but in time should develop a voice worth listening to.

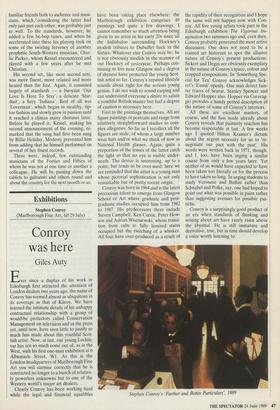

Stephen Conroy's 'Further and Better Particulars', 1989

Previous page

Previous page