A SYMBOL IN SEARCH OF MEANING

Amity Shlaes reports that Germany is a little

divided — over the merits of the use of a million square feet of wrapping

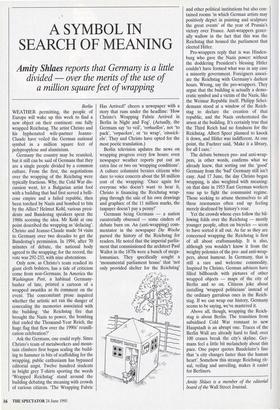

Berlin WEATHER permitting, the people of Europe will wake up this week to find a new object on their continent: one fully wrapped Reichstag. The artist Christo and his hyphenated wife-partner Jeanne- Claude have veiled the German national symbol in a million square feet of polypropylene and aluminium.

Germany the country may be reunited, but it still can be said of Germans that they are a single people divided by a common culture. From the first, the negotiations over the wrapping of the Reichstag were typically fractious. Why, the Cold War dis- cussion went, let a Bulgarian artist fool with a building that had first served a belli- cose empire and a failed republic, then been torched by Nazis and bombed to bits by the Allies? Helmut Kohl, various presi- dents and Bundestag speakers spent the 1980s scorning the idea. Mr Kohl at one point described the wrapping as 'defacing'. Christo and Jeanne-Claude made 54 visits to Germany over two decades to get the Bundestag's permission. In 1994, after 70 minutes of debate, the national body agreed to the wrapping; for the record, the vote was 292-233, with nine abstentions.

Only now, as Christo's team readied its giant cloth bolsters, has a tide of criticism come from non-Germans. In America the Washington Post, a habitual Germany- basher of late, printed a cartoon of a wrapped swastika as its comment on the event. The concomitant prose inquired whether the artistic act ran the danger of concealing the memories associated with the building: 'the Reichstag fire that brought the Nazis to power, the bombing that ended the Thousand-Year Reich, the huge flag that flew over the 1990s' reunifi- cation celebration?'

Ask the Germans, one could reply. Since Christo's team of metalworkers and moun- tain climbers first began scaling the build- ing to hammer in bits of scaffolding for the wrapping, public enthusiasm has bypassed editorial angst. Twelve hundred students in bright grey T-shirts sporting the words `Wrapped Reichstag' stand around the building debating the meaning with crowds of curious citizens. 'The Wrapping Fabric Has Arrived!' cheers a newspaper with a story that runs under the headline: 'How Christo's Wrapping Fabric Arrived in Berlin in Night and Fog'. (Actually, the Germans say 'to veil', `verhuellen', not 'to pack', `vetpacken', or 'to wrap', `einwick- ebe They and Christo have opted for the most poetic translation.) Berlin television updates the news on wrapping progress every few hours: even newspaper weather reports put out an extra line or two on 'wrapping conditions'. A culture columnist berates citizens who dare to voice concern about the $8 million cost of the wrapping: 'Once again for everyone who doesn't want to hear it, Christo is financing the Reichstag wrap- ping through the sale of his own drawings and graphics: of the 11 million marks, the taxpayer doesn't pay a penny!'

Germans being Germans — a nation curatorially obsessed — some cinders of debate burn on. An (anti-wrapping) com- mentator in the newspaper Die Woche parsed the history of the Reichstag for readers. He noted that the imperial parlia- ment that commissioned the architect Paul Wallot in the 1870s were a bunch of mega- lomaniacs. They specifically sought a `monumental parliament house' that 'not only provided shelter for the Reichstag' and other political institutions but also con- tained rooms 'in which German artists may positively depict in painting and sculpture the great events' of the year of Prussia's victory over France. Anti-wrappers gener- ally wallow in the fact that this was the Reichstag that housed the parliament that elected Hitler.

Pro-wrappers reply that is was Hinden- burg who gave the Nazis power: without the doddering President's blessing Hitler couldn't have formed what was in any case a minority government. Foreigners associ- ate the Reichstag with Germany's darkest hours. Wrong, say the pro-wrappers. They argue that the building is actually a demo- cratic symbol and a victim of the Nazis, like the Weimar Republic itself. Philipp Schei- demann stood at a window of the Reich- stag to declare the creation of that republic, and the Nazis orchestrated the arson at the building. It's certainly true that the Third Reich had no fondness for the Reichstag. Albert Speer planned to knock it down, and Hitler was indifferent. At one point, the Fuehrer said, 'Make it a library, for all I care.'

The debate between pro- and anti-wrap- pers, in other words, confirms what we already knew, that sorting out the 'good' Germany from the 'bad' Germany still isn't easy. And 17 June, the day Christo began wrapping, is also weighted with meaning: on that date in 1953 East German workers rose up to fight the communist regime. Those seeking to attune themselves to all these resonances often end up feeling merely deafened by history's roar.

Yet the crowds whose eyes follow the bil- lowing folds over the Reichstag — mostly younger people, often on bicycles — seem to have sorted it all out. As far as they are concerned wrapping the Reichstag is first of all about craftsmanship. It is also, although you wouldn't know it from the weighty polemics of the pro- and anti-wrap- pers, about humour. In Germany, that is still a rare and welcome commodity. Inspired by Christo, German advisers have filled billboards with pictures of other wrapped objects — maps of the city of Berlin and so on. Citizens joke about installing 'wrapped politicians' instead of the ordinary garrulous ones in the Reich- stag. If we can wrap our history, Germany seems to be saying, we've mastered it.

Above all, though, wrapping the Reich- stag is about Berlin. The transition from subsidised Cold War remnant to new Haupstadt is an abrupt one. Traces of the Berlin Wall are already hard to find; over 100 cranes break the city's skyline. Ger- mans feel a little bit melancholy about this pace. One paper quotes Baudelaire's line that 'a city changes faster than the human heart'. Somehow this strange Reichstag rit- ual, veiling and unveiling, makes it easier for Berliners.

Amity Shlaes is a member of the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal.

Previous page

Previous page