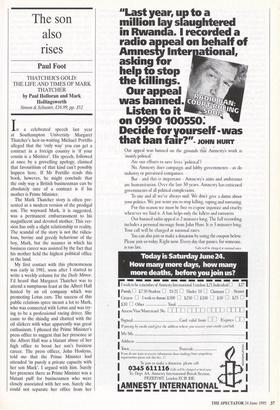

The son also rises

Paul Foot

THATCHER'S GOLD: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF MARK THATCHER by Paul Holloran and Mark Hollingsworth Simon & Schuster, £16.99, pp. 352 In a celebrated speech last year at Southampton University Margaret Thatcher's heir-in-waiting Michael Portillo alleged that the 'only way' you can get a contract in a foreign country is 'if. your cousin is a Minister'. His speech, followed at once by a grovelling apology, claimed t hat favouritism of that kind can't possibly happen here. If Mr Portillo reads this book, however, he might conclude that the only way a British businessman can be absolutely sure of a contract is if his mother is Prime Minister.

The Mark Thatcher story is often pre- sented as a modern version of the prodigal son. The wayward Mark, it is suggested, was a permanent embarrassment to his magnificent and devoted mother. This ver- sion has only a slight relationship to reality. The scandal of the story is not the ridicu- lous, bovine and greedy behaviour of the boy, Mark, but the manner in which his business career was assisted by the fact that his mother held the highest political office in the land.

My first contact with this phenomenon was early in 1981, soon after I started to write a weekly column for the Daily Mirror. I'd heard that Margaret Thatcher was to attend a sumptuous feast at the Albert Hall hosted by an oil company which was promoting Lotus cars. The success of this public relations spree meant a lot to Mark, who was connected with Lotus and was try- ing to be a professional racing driver. She came to the shindig and chatted with the oil slickers with what apparently was great enthusiasm. I phoned the Prime Minister's press office to suggest that her presence at the Albert Hall was a blatant abuse of her high office to boost her son's business career. The press officer, John Hoskyns, told me that the Prime Minister had attended 'in purely a private capacity with her son Mark'. I argued with him. Surely her presence there as Prime Minister was a blatant puff for businessmen who were closely associated with her son. Surely she could not separate her office from her `private capacity' on such a public occasion. Hoskyns did not agree. He, like Margaret Thatcher, as these authors put it, 'could not see anything wrong'. Mark's use of the Thatcher name and the Downing Street kudos to fill his pockets proved only that Mark was 'merely being a Thatcherite'.

Thus the book is full of examples of meals and receptions at 10 Downing Street and at Chequers where the guests, either on their own or with others, were business- men with whom Mark was seeking a favour or a deal. Every one of these, it seems to me, was in clear breach of Churchill's 1952 principle: 'Ministers must so order their affairs that no conflict arises or appears to arise between their private interests and their public duties.' The Thatchers' oblivi- ousness to this was perhaps more than any- thing else responsible for the rapid slide of British politics in the 1980s and 1990s into what is now know as sleaze.

The question which matters, and which this book confronts courageously is: how much is a Prime Minister entitled to assist her family's business? The book is less impressive when it sets off in hot pursuit of two much more trivial questions — how rich is Mark Thatcher, and where did he get his money from? Here, as the authors freely concede, they are balked by the cocoon of secrecy which 'middlemen' like Thatcher weave around them. There are no published accounts, no declarations of income, no responsibility or accountability to anyone at all.

The sources of such information are, therefore, necessarily, political enemies, cheated or disgruntled former colleagues, or plain old-fashioned speculation derived from the show of wealth: the flash cars, the houses, the swimming pools, the butler, which are as likely to disguise reality as to disclose it. As a result, despite constant boasting to the contrary, the authors have conspicuously failed to answer their own questions. Their grandest claim — that Mark took £20m from the Al Yamamah arms deals negotiated by his mother with the Saudi Arabian government — relies in the main on a dubious tape-recording already published in the Sunday Times.

If Thatcher did pocket a hefty Al Yamamah commission, that is probably the nastiest British political corruption story this century. But these authors have only asserted it; they have not proved it. Nor is it even half credible, as they assert, that the reason for the alleged commission was that `Mark supplied a conduit and direct route for Wafic Said and Prince Bandar to nego- tiate with the Prime Minister, by-passing official channels'. If the Saudi Royal family and the British Prime Minister want to make deals, they make deals. They do not need official channels, still less a `conduit'.

The authors rely heavily on stories already told: the shocking story of the Oman University contract was told by the Observer more than ten years ago. Mark's disastrous sortie into the aviation fuel busi- ness with Ameristar was thoroughly exposed by Today. The authors' surveys of Mark's involvement in other areas — Sri Lanka, for example, Kenya or Nigeria end by adducing no evidence of any vast wealth accruing to Mark from any of these places. From Turkey, where Mark and an accomplice went, following his mother's official visit, and, most remarkably, from South Africa where the Thatcher family have been doing business for 50 years, and where Mark was engaged in all sorts of deals, the book has no news at all. Did Mark Thatcher, as Tiny Rowland claimed, go to Brunei to discuss lucrative building contracts with the Sultan? No reply here. Even in Malaysia, where the involvement of Mark's henchman, Steve Tipping, in the huge arms deals of the late 1980s has been well documented, the authors must con- cede that Mark's 'take', if there was one, is `difficult to ascertain'.

All in all, the extent and origin of Thatcher's Gold are almost as mysterious at the end of the book as they are at the beginning. The combination of greed and secrecy which has so effectively enriched the rich in the last decade and a half has bred in the few dissenting journalists a preference for impatient assertion rather than proof, and for half-baked colloquial conjecture which always lets the victims off the hook. There is a kind of snake here all right. These authors have scotched it, not killed it.

Previous page

Previous page