ARTS

Exhibitions

Rites of passage: art for the end of the century (Tate Gallery, till 3 September)

Being skinned alive

Marina Warner

Wen did words like 'terrific' and `tremendous' become intensive forms of praise? It must have been an effect of the quest for the sublime, of the taste for yawn- ing abysses and icy wastes and echoing tun- dra, though the OED only gives rather recent examples for the use of such terms of critical delight. Today, 'awesome' is on the street, alongside 'weird' and 'wicked', and the preoccupations and intentions of contemporary artists reflect this shift in val- ues and desires. The Tate's ambitious and fascinating show, Rites of Passage, is mani- festly taking the pulse of times: it doesn't aim to provoke terror, to be 'terrific' in the old religious sense of the word, but several of the works selected deliberately court danger — both for the artist and the audi- ence — others deal in intimate exposure and in flayings of one kind or another; yet others confront disease, annihilation, death. It's subtitled art for the end of the century and an implicit appeal to squeamishness, an lhtention to dismay, to turn the cheek pale and ghastly — to appal — animate the character of the show as a whole, if not the individual artists' enter- prise. So it may be that 'ghastly' and `appalling' will be following the same pat- tern as 'awesome' and 'wonderful' and come to mean the equivalent of 'it knocked me out'.

The sequence of artists has been very thoughtfully orchestrated by the curators, Stuart Morgan and Frances Morris (of the Tate), as a ritual passage in itself, trans- porting the visitor from the embodied and deliberately prosaic (John Coplans's naked self-portraits) to an unearthly and meta- physical conclusion with Miroslaw Balka's concrete effigies. Coplans's huge, headless photographs fill the first room with intima- tions of mortality, and the public then pass- es between two columns of his heroically posed, unflinchingly mapped, ageing flesh, into the next chamber, where Mona Hatoum's self-portrait is playing in a tondo in the floor under a cupola. The convexities here of her mirrored image have been made by state-of-the-art fibre optic surgical cameras probing her to the depths. To a live synchronised sound track of panting and gurgling, we enter her ear, her throat, her innards, and swoop through ridged ravines and swelling pillows of her glisten- ing mucous and rosy interior.

The artists of Rites of Passage reveal the new millennialist obsession with skin, as the ultimate container of self and the boundary between it and all else. Yet skin is so fragile, so unequal to the task of indi- vidual definition. Here is the already noto- rious Vanitas jeu d'esprit by Jana Sterbak, the 'Flesh Dress' made of steak sutured by the artist to hang on a window display dummy; the same artist has made a barbed wire Robe of Nessus which heats up, called 'I want you to feel the way I do.' Pain is the only way to make the body feel real, to guarantee its sensory presence — this is a fine art variation on body-piercing.

But those images of skinning and being skinned are modish capriccios compared to Hamad Butt's delicate explorations of fleshly frailty. Butt called his experiments with a new alchemy `metachemics' (by analogy with metaphysics). Wafer-thin glass alembics and phials contain poisonous halogen gases, and look as if they might shatter any moment. Hamad Butt, who died of Aids last year at the age of 32, took serious risks in the handling of these volatile substances to create a remarkable allegory of his own death, and by extension, the continuing danger to us all.

Butt's work does however offer a way to look at the art in Rites of Passage that dif- fers from a first impression of passive masochism and lip-smacking morbidity. The catalogue includes an interview with Julia Kristeva about her idea of the 'abject' at the fin-de-siecle, and artists' concentra- tion on 'the impossible . . . the disgusting . . . the intolerable', on 'dirt and ugliness and regression'. But this stress may be a bit misleading. Coplans after all clenches his hands defiantly in his photographs, and if you wash your eyes of Drakkar and Calvin Klein ads, his body isn't repellent at all, but dignified (as well as rather sweet and furry); Hatoum's roller-coaster through her own viscera could be seen as a wonder of a kind — it resonates with le gai savoir after all, and again, if you think yourself into a doc- tor's frame of mind, her insides look posi- tively in the pink.

Hamad Butt is no reluctant Faust, either, overcome with disgust at man's corruption; but a seeker, a quester. His room is a remarkable monument to a young and exciting mind enraptured by the Red Room (The Parent), mixed media, by Louise Bourgeois, 1994 possibilities of terra incognita for art using science. His is a huge loss.

In his introduction, Stuart Morgan gently floats the idea that artists today have taken on a priestly role — psychopomps conduct- ing souls through the mysteries. He invokes the French passeur, or ferryman, who pre- sides over rites, and it is the arch-shaman Joseph Beuys who has been placed at the very crux of the show, with his 'Earthquake in the Palazzo', a highly symbolic piece, made in 1981, full of precarious balancing acts, and littered with shattered glass (the violent promise of revolutionary uplift spoiled, to my eyes, by the office grey twill carpet). A conjuror, a magician in the exciting and suspect tradition of Mesmer or Svengali, Beuys was also a can-do, feel- good exhorter to self-improvement and spiritual growth, and his presence interest- ingly undermines the obeisance to terminal gloom which the show sometimes seems obliged to make. Here is an artist in 1981, at the very time Kristeva was diagnosing abjection as the mal-du-siecle, still promis- ing, still believing in, transformation.

The most interesting work of living artists with rites of passage is not ultimately despairing either, in spite of the flayed company it keeps. Some of• it, like Butt's, even relies on those enlightened powers of inquiry and reason to probe mysteries: Susan Hiller's video dramatisation of Punch & Judy (An Entertainment) explores the traditional puppet show as a ritual combat with death: a series of ferocious scarlet, leering Mr Punches pit their irre- pressible vitality against all assailants, including Mister Death. Hiller studied anthropology, and her piece reflects her understanding of ritual as a social ceremo- ny defining a community's experience: Punch is a British Everyman complete with dog, and raucous children's laughter on the sound-track is their only defence against his violence and his sorrows.

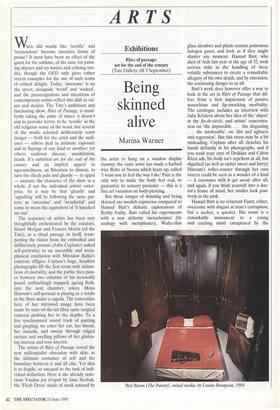

Louise Bourgeois and Miroslaw Balka, in the two most memorable rooms in the show, have made haunting records of more private transitions: Bourgeois's sumptuous scarlet cells are encircled by doors such as open and close in dreams and are filled with enigmatic objects. Her own room as a child becomes transformed into a fairytale spinner's dream chamber, dominated by a strange loom-cum-hatstand holding many large spools of red and blue thread, while whorled glass vials and mirrors stand around, reflecting; sculpted red wax hands appear here and there — a sculptor's affir- mation of her own strength and creative powers. Besides this lair, the parents' bed- room reveals a bright blood-red bed and an ominous bag of plasma above it. (The mar- vellous assembly of pieces makes this visi- tor long to go to the current retrospective of Bourgeois's work at the Pompidou Cen- tre in Paris.) The Polish sculptor Balka's `Remembrance of the First Holy Commu- nion', a concrete sculpture of himself as a child on the day of the ceremony, is the only work in the show explicitly represent- ing a religious ritual, but it is his Shep- herdess, a lone, hooded and faceless phantom pointing with a light from an empty sleeve at a small lost head on the ground, that sums up the show's longing for reparation. For the human failure it pictures and resists is only primarily decay, ageing, disease or the several ills that mod- ern flesh so hates being heir to; the loss it records is above all the loss of reciprocity. There are no conjunctions except the chemical variety in these art works, no unions, no rituals of sex, marriage, procre- ation; only radical solitude, as if imaging the self through the application of imagina- tive and technical ingenuity could turn that appalling vulnerability of surface and skin into protective armour. The promise of these priests encompasses the healing effects of confrontation and analysis, but fails before the discomforts of love.

Previous page

Previous page