Gallery guide

Philip Kleinman

In Piccadilly you've still got time to visit the Royal Academy summer exhibition at Burlington House or, if you walk down the street, the ISBA exhibition at Reed House. Tastes vary, and you may prefer to pop along to the V and A, where they're showing Chinese jade, or Waterloo Station, where you can see what I'm inclined to consider the outstanding artistic achievement of the year, the new Folon.

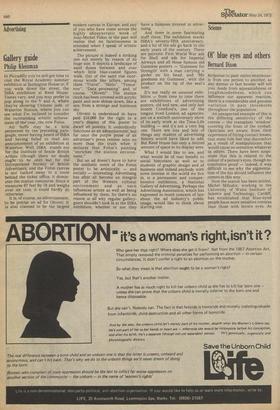

Act buffs may be a little perplexed by the preceding paragraph, never having heard of ISBA and having failed to read any announcement of an exhibition at Waterloo. Well, ISBA stands not for the Institute of Senile British Artists (though there no doubt ought to be one) but for the. Incorporated Society of British Advertisers; and the Folon canvas is not tucked away in a room behind the ticket office, it dominates the station concourse. Since it measures 67 feet by 18 and weighs over six tons, it could hardly do otherwise.

It is, of course, an advertisement, to be precise an ad for Olivetti. It is also claimed to be the largest modern canvas in Europe, and any of you who have come across the highly idiosyncratic work of Jean-Michel Folon in the past will realise that no facetiousness is intended when I speak of artistic achievement.

The picture is indeed a striking one not merely by reason of its huge size. It depicts a landscape of sand dunes between and over which little blue-coated figures walk. Out of the sand rise enormous words like pillars, among them "Travel", "Hello", "Tomorrow", "Data processing" and, of course, "Olivetti". The station clock has been covered with acrylic paint and now shines down, like a sun, from a strange and luminous sky.

Olivetti is understood to have paid £10,000 for the right to a year's display of this poster to dwarf all posters. It undoubtedly functions as an advertisement, but for once the purple prose of an advertiser's press release says no more than the truth when it declares that Folon's painting "enriches the station environment."

But an ad doesn't have to have the aesthetic merit of the Folon poster to be artistically — and socially — interesting. Advertising has after all become an integral part of the Western cultural environment and as such influences artists as well as being influenced by them. So there's no reason at all why regular gallerygoers shouldn't look in at the ISBA exhibition, whether or not they

have a business interest in advertising.

And there is some fascinating stuff there. The exhibition marks ISBA's seventy-fifth anniversary, and a lot of the ads go back to the early years of the century. There are patriotic First World War ads for Shell and ads for Imperial Airways and all those famous old Guinness posters — 'Guinness for Strength' with a man carrying a girder on his head, and 'My goodness my Guinness', with the product on the tip of the seal's nose.

It's not really an unusual exhibition — from time to time there are exhibitions of advertising posters, old and new, and only last month Crawford's, one of the longest lived London ad agencies, put on a sixtieth anniversary show of its early work at the Time-Life building — and it's not a very big one. There are lots and lots of things any student of advertising history would have liked to add. But Reed House has only a limited amount of space in its display area. 7 What I would like to see, and what would be of real benefit to social historians as well as to students of graphic design and of business and indeed anybody with some interest in the world we live in, is a permanent and comprehensive exhibition, a National Gallery of Advertising. Perhaps the Advertising Association, which has expressed so much concern of late about the ad industry's public image, would like to think about slatting one.

Previous page

Previous page