TYRANNY OR LICENCE

Richard West on Spain's

continuing tension between Right and Left

Avila THE campaign leading up to the general election on 22 June, is matched for interest in the Spanish press by the torrent of reminiscences on the 50th anniversary of the Civil War, which started on 18 July, 1936. Most of the articles and the serials concern the battles, featuring interviews with the ancient survivors, most of whom are as fierce and partisan as ever, although I did see a photograph of two former opponents shaking hands, where they had once tried to kill each other, beside the Ebro. The most disturbing, because the most savage memoirs are those that deal not with the war itself, but the civil commotion leading up to Franco's in- surgency, especially the murder and persecution of priests and nuns by anarch- ist gangs, and the kidnapping and murder of left-wingers by fascist gangs. The pre- sent municipality of Madrid, which is run rather like Ken Livingstone's Greater Lon- don Council, had published a very tenden- tious account of what went on in Madrid in May 1936, provoking a savage reply in the pro-Fascist newspaper El Alcazar, which has a big sale in towns such as Avila. A columnist has described how, as a child in May 1936, he was kept awake by the moans and sobs of a nun, who had been beaten up by `socio-communists'.

The violence and terror, coming on top of bloody industrial disputes (not unlike our coal strike and riots at Wapping) created an atmosphere in parts of Spain like Beirut today, or Belfast. Yet the elected government and the Republic itself undoubtedly had the support of the great majority of the Spanish people. The terror- ists of the Left and Right were fringe minorities. The Civil War did not come as a thunderstorm in a blue sky; yet few people could have predicted at the begin- ning of 1936 that Spain would so suddenly slide towards anarchy and then war.

The recollection of 50 years ago, con- stantly aired in the press and television, has brought a certain unease to Spaniards. Once again there is a popular Socialist government, likely to win at next month's election. The rival parties also contend for the moderate middle ground. The anarch- ist, anti-clerical Left has virtually dis- appeared, and the Communists have a moth-eaten appearance. The clerical, monarchist section of society now can content itself that Spain once more has a Christian king, even if I have heard him described, here in Avila, as a pawn of the Socialists. Although Spain has 20 per cent unemployment, those who are in work consider themselves to be much better off then they were five or ten years ago. Spain is glad to be in the Common Market and Nato; it is losing its sense of inferiority, or backwardness. Most of the politicians call themselves by the strangely old-fashioned title 'progressive', although here in Avila, one man told me proudly that he was 'not a conservative but a reactionary'.

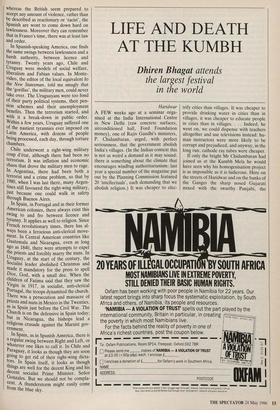

Yet stable as Spain appears to be, the fear remains that it all might suddenly crumble. There are still some elements of the authoritarian Right, in the armed forces especially. They tried five years ago to seize the Parliament in a coup d'etat that was put down largely thanks to the firm- ness of the King. As reported last week, a senior army officer and venous anti-semitic Christian fanatics have been applying for funds to Colonel Gaddafi, who also fi- nances the Eta or Basque terrorist move- ment. Eta have been busy recently. They blew up and killed five policemen in Madrid; they nearly killed a judge; and they murdered a 71-year-old Communist in San Sebastian, a case of mistaken identity as they admitted afterwards. The Eta leader, or anyway the most publicised gangster, Domingo Iturbe Abasolo, known as 'Txomin', was recently jailed again by the French and may be extradited. From the articles on 'Txomin' (pronounced Cho- min) it seems he started life as a fanatical football supporter, only later transferring his zeal to separatist politics. Although he seems to have no ideological interests, `Txomin' has acquired the jargon of Marx- ism. Once, rejecting a government amnes- ty, and promising that the 'executions' (ie. murders) would go on, Txomin explained to his followers that executions accentu- ated the contradictions in bourgeois demo- cracy, bringing to light the real powers in the state, the army and capital. Another Eta leader said recently that they would not be content with talks with the King or the head of the army. They wanted to talk with the Pentagon. In Spain, as in most countries afflicted with terrorism, the mania can appear in national, ideological form, or as a separat- ist movement. It has appeared as an ideological movement in for instance West Germany (the Baader-Meinhof gang), Ita- ly, Argentina, and Uruguay, but as a regional separatist movement in the British Isles, India, Sri Lanka and Yugoslavia. Strangely enough, it seems that the terror- ist instinct is satisfied by either the ideolo- gical or the separatist movement. English left-wing terrorists find a satisfactory outlet for their violence in the activity of the IRA. Sicilian separatists can sympathise with the northern sociology graduates of the Red Brigades. In Spain, 50 years ago, the Basque and Catalan separatists were content in the knowledge that anarchists were murdering nuns in Castile. The, anarchists in Madrid today are satisfied with the work of 'Txomin'. The two kinds of terrorists, the ideological and the separ- atist, are not in fact trying to achieve an end, such as classless society or an inde- pendent Basque or Irish state. They want death, destruction and terror, for their own sake. This explains why in Spain, as in Ireland, the terrorists of ostensibly rival, opposed factions can all get support from Colonel Gaddafi.

The terrorism in Spain is not perhaps as serious as the great rise in the level of crime and public violence. In Seville, mugging is rampant. Housebreaking has made life almost insupportable for the retired people from northern Europe vvh° live on the south coast. Parts of Marin', and Barcelona are terrorised by gangs of `punkies'. I hasten to point out that no- where in Spain has reached the state of crime and lawlessness that is found say, Liverpool, or south London. But

whereas the British seem prepared to accept any amount of violence, rather than be described as reactionary or 'racist', the Spanish are wont to come down hard on lawlessness. Moreover they can remember that in Franco's time, there was at least law and order.

In Spanish-speaking America, one finds the same swings between lawlessness and a harsh authority, between licence and tyranny. Twenty years ago, Chile and Uruguay were models of social welfare, liberalism and Fabian values. In Monte-

video, the editor of the local equivalent fo the New Statesman, told me smugly that

the 'gorillas', the military men, could never take over. The Uruguayans were too fond of their party political systems, their pen- sion schemes and their unemployment benefits. Then the terrorism started, and with it a break-down in public order. Within a few years, Uruguay suffered one of the nastiest tyrannies ever imposed on Latin America, with dozens of people being processed, each day, through torture chambers.

Chile underwent a right-wing military coup d'etat, although there had been no terrorism. It was inflation and economic chaos that drove the military men to rage. In Argentina, there had been both a terrorist and a crime problem, so that by 1980, when I was last there, many Argen- tines still favoured the right-wing military, just because one could walk in safety through Buenos Aires.

In Spain, in Portugal and in their former American colonies, there always exist this swing to and fro between licence and tyranny. It applies as well to religion. Since French revolutionary times, there has al- ways been a ferocious anti-clerical move- ment. In Central American countries like Guatemala and Nicaragua, even as long ago as 1840, there were attempts to expel the priests and forcibly marry the nuns. In Uruguay, at the start of the century, the Socialist leader abolished Christmas and made it mandatory for the press to spell Dios, God, with a small dee. When the children of Fatima said that they saw the Virgin in 1917, in socialist, anti-clerical Portugal, the troops dynamited the church. There was a persecution and massacre of priests and nuns in Mexico in the Twenties,

as in Spain just before the Civil War. The Church is on the defensive in Spain today; but in Nicaragua, the bishops lead a religious crusade against the Marxist gov- ernment.

In Spain, as in Spanish America, there is a regular swing between Right and Left, or whatever one likes to call it. In Chile and Paraguay, it looks as though they are soon going to get rid of their right-wing dicta- tors. In Spain itself, it looks as though things are well for the decent King and his decent socialist Prime Minister, Senor Gonzales. But we should not be compla- cent. A thunderstorm might easily come from the blue sky.

Previous page

Previous page