FINE ARTS SPECIAL Art

A gentle kick up the macho rump

Clare Rendell on the beneficial effects of a new collection of women's art Ruskin always said that no woman could paint, but even he was fulsome in his praise for Lady Butler, whose sombre com- memoration of the Crimean War had the crowds bursting the barricades at the Royal Academy. A similar mood of enthusiasm has greeted the recently acquired collection of women's art at New Hall, Cambridge. The exclusively female nature of the collec- tion happily forestalls tiresome questions about equality of representation and offers some unexpected benefits, not least the opportunity to reassure latterday Ruskins that overt or tacit feminism need not pre- clude talent. The fact that this collection is also a triumph of private enterprise with some unorthodox economic implications merely underlines its historic status.

Inspired by Mary Kelly's gift of her work `Extase' following her stay as artist in resi- dence in 1986, the president of New Hall, Valerie Pearl, wrote to a number of women artists in Britain to share her hopes of developing a collection of 20th-century art by means of donations from distinguished women artists. It is rather ironic that while she was expressing these hopes the paint- ings on show at New Hall were all by men, although this might simply reflect the bias of the Arts Council collection from which they were borrowed.

Yet, despite New Hall's earlier lack of attention to women's art, an overwhelming majority of the artists approached respond- ed favourably to the president's initiative. The assurance that their gifts would never be de-accessioned and the promise of per- manent showing must have been persuasive inducements, but the general readiness to donate rather than loan the works is harder to explain. I doubt whether the president of Grumbleweed Polytechnic would have elicited the same response: the lure of elitism is obviously a strong one.

The organisers admit that New Hall's status as a women's college was responsible for the success of their appeal and was the reason why men were not approached. But a more accurate explanation of their suc- cess lies in the ability of New Hall staff to make contacts beyond the pale of educa- tion and arouse generosity in a wide variety of people. Their fund-raising efforts began with the foundation of New Hall itself: many years of strenuous campaigns and coffee mornings throughout the 1950s were needed before a college could be built to achieve their aim of increasing the educa- tional opportunities for women at Cam- bridge.

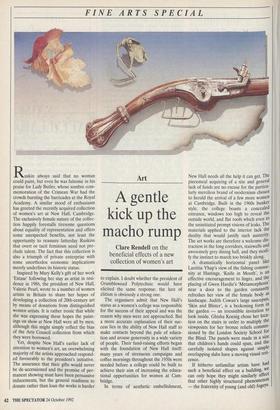

In terms of aesthetic embellishment, New Hall needs all the help it can get. The piecemeal acquiring of a site and general lack of funds are no excuse for the particu- larly merciless brand of modernism chosen to herald the arrival of a few more women at Cambridge. Built in the 1960s bunker style, the college boasts a concealed entrance, windows too high to reveal the outside world, and flat roofs which even to the uninitiated prompt visions of leaks. The materials applied to the interior lack the duality that would justify such austerity. The art works are therefore a welcome dis- traction in the long corridors, stairwells and awesomely grey dining hall, and they modi- fy the instinct to march too briskly along. A dramatically horizontal panel like Laetitia Yhap's view of the fishing commu- nity at Hastings, 'Knife in Mouth', is an effective encouragement to linger, and the placing of Gwen Hardie's 'Metamorphosis near a door to the garden constantly refreshes her view of the female body as landscape. Judith Cowan's large saucepan, , 'Skin and Blister', is a beckoning form in the garden — an irresistible invitation to look inside. Ghisha Koenig chose her loca- tion on the stairs in order to multiply the viewpoints for her bronze reliefs commis- sioned by the London Society School for the Blind. The panels were made in a size that children's hands could span, and the carefully isolated shapes against simple overlapping slabs have a moving visual reti- cence. If hitherto unfamiliar artists have had such a beneficial effect on a building, WC can only hope they might similarly affect that other highly structured phenomenon — the fraternity of young (and old) fogeYs.

This macho rump of romantics has created in its own image a premier league of artists, yet fails to realise that their symbiotic rela- tionship is the very source of the stagnation they deplore in contemporary art. The shattered crockery of Julian Schnabel, the cleverly bleeding television of Richard Hamilton, the restless expressionism of Francesco Clemente and all the other over- exposed exhibitors on the international cir- cuit are a dispiriting sight. But staying within such well-marked territory is evi- dently not so demanding as opening the mind to a broader range of new work.

Perhaps we should take the advice of the greatest fogey of all and pay some attention to the British tradition. In the hands of artists like Freud, Paolozzi, Sandie, Frink and Kitaj, the British tradition has never looked so good. The collection at New Hall reveals many who can enrich this canon. Alongside well-known names like Bridget Riley, Maggie Hambling, Sandra Blow, Paula Rego, Anne Redpath and Valerie Thornton, and younger talents like Sarah Cawkwell, Sophie Ryder, Jo Stockham and Mary Husted, there are other artists who arrest attention. The suffering figure in Evelyn Williams's painted relief 'All Night Through' is almost unbearable to look at. Equally macabre but more objective in their concern for the severed head of a criminal are Ana Maria Pacheco's etchings, inspired by Penderecki's opera The Devils of Loudun. At the other end of the spectrum, Alexis Hunter gives us Essex man at his most androgynous in her photo series Approach to Fear XI— Effeminacy Productive Action. The small abstract watercolour 'Star Yard in Africa' by Mali Morris has a disarming simplicity.

Because of the variety of demands on their time, women artists have found it hard to give high priority to marketing their work and fostering their reputations. It is more common for men to define them- selves as career artists, and this is clearly reflected in the higher proportion of men in contemporary exhibitions. The perma- nent visibility guaranteed to New Hall's collection will make it an ideal reference point for exhibition selectors. The major instigator of New Hall's collection, Ann Jones of the South Bank Centre, is enthusi- astic about its potential as a catalyst for future developments like solo shows and teaching fellowships at the college, attract- ing private as well as public funds. The greatest generosity lies with the artists who have donated their work. To see valuable pieces by famous names hanging alongside those by the relatively unknown is to enjoy a rare pleasure in which questions of mon- etary value do not interfere with aesthetic enjoyment.

Women's Art at New Hall may be viewed by appointment (telephone 0223 351721). A catalogue is available at .f2.

'Blind School: Cooking Class', 1987 bronze relief by Ghisha Koenig (b. 1921)

Previous page

Previous page