Exhibitions 1

The Swagger Portrait: Grand Manner Portraiture in Britain from Van Dyck to Augustus John (Tate Gallery, till 10 January)

Dashing depictions

Giles Auty

This week I welcome an unusual exhibi- tion, the title of which sounds uncannily like someone's specialist subject for Master- mind. To the best of my belief, Andrew Wilton, keeper of the British Collection at the Tate Gallery, who organised this show, has not appeared yet on that entertaining programme.

What is a swagger portrait? Etymologists A typical Spectator reader of his time: 'Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby', 1870, by Tissot might aver that to swagger describes some- thing a touch more active than sitting for a portrait. Clearly it is necessary to move in order to sway or swag. This is just the sort of subject on which my late father used to hold forth at length during strolls through the countryside.

However strained its etymological origin, here is an exhibition to enlighten and entertain, and much the same may be said of the catalogue essay written by Mr Wilton. Regrettably, many of the catalogue essays which seek to explain exhibitions of more modern art have become virtuallY unreadable, their authors struggling des- perately to assemble their thoughts in any coherent form. Thus recent written materi- al accompanying an exhibition at the Tate of Richard Hamilton's work contained the remarkable assertion that God is dead, although where and when this took place was not specified. The Swagger Portrait exhibition, which spans the years 1630- 1930, is a historic record of a time when that remarkable old gentleman was still held to be extant, together with more clear- ly defined human hierarchies than those prevailing today. One of the purposes .of the swagger portrait might be seen as rein- forcing such social divisions. Artists even of the ability of Van Dyck, Batoni and Reynolds were essentially flatterers of the powerful, as were Winterhalter and Sar- gent, and it is this last aspect which is the least agreeable for me of their virtuoso dis- plays of painting skills. It is also the factor that distinguishes artists even of such stamp from their more important counter - parts, not least in portraiture: Velazquez, Rembrandt, Goya, Manet, Degas. The curtain rises on this exhibition with Van Dyck's portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria, painted for Charles I. Like most such paintings of the era, it has its share of interesting symbolism: oranges and a mon- key under restraint referring to the Queen's success in subduing unchaste desires. In an adjacent portrait of Venetia

Stanley as Prudence, Van Dyck summons a full symbolist panoply: this time the virtu- ous lady crushes naughty Cupid beneath her pretty foot.

Most of the portrayers of British nobility were imports during this and subsequent eras: Van Dyck himself, Lely, Huysmans, Kneller, de Wet, Closterman, Grisoni. Indigenous British art made something of a belated start, signalled for many by the dis- tinctive humanism of Hogarth. The latter's virtuous 'Captain Coram', founder of the Foundling Hospital, brings a welcome human robustness to the ranks of gilded sitters, while an adjacent portrait by Grisoni of 'Colley Cibber as Lord Fopping- ton' is held by many who have seen it to be remarkably reminiscent of one of my more distinguished critical colleagues.

It can be an amusing exercise to imagine figures from historic paintings dressed in Contemporary clothes as a way of making the works themselves seem less remote. Such an exercise works especially well with Vermeer's 'A Woman in Blue Reading a Letter', say, and can help stress the true timelessness of works by the greatest mas- ters. However, such exercises are more dif- ficult in the face of many of the works in the current exhibition because the ceremo- nial finery worn often plays an important Part in the creation of visual impact: Gains- borough's wonderful 'John Campbell, 4th Duke of Argyll' being a typical case in Point. By contrast, the same artist's 'Mr and Mrs Hallett (The Morning Walk)' dig- nifies two young people with rio greater claim to fame than an early and successful marriage. It is one of the more touching and beautiful works of the entire 79 on Show.

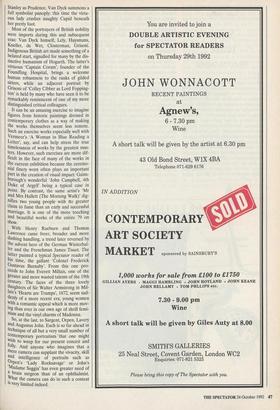

With Henry Raeburn and Thomas Lawrence came freer, broader and more dashing handling, a trend later reversed by the advent here of the German Winterhal- ter and the Frenchman James Tissot. The latter painted a typical Spectator reader of his time, the gallant 'Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby'. From this one pro- ceeds to John Everett Millais, one of the greater and more wasted talents of the 19th century. The faces of the three lovely daughters of Sir Walter Armstrong in Mil- la's's 'Hearts are Trumps', 1872, seem sud- denly of a more recent era, young women With a romantic appeal which is more mov- ing than ever in our own age of shrill femi- nism and the vinyl charms of Madonna. So, at the last, to Sargent, Orpen, Lavery and Augustus John. Each is so far ahead in technique of all but a very small number of cOntemporary portraitists that one might wish to weep for our present conceit and folly. And anyone who imagines that a Mere camera can supplant the vivacity, skill and intelligence of portraits such as ,Orpen's 'Lady Rocksavage' or John's Madame Suggia' has even greater need of a brain surgeon than of an ophthalmist. .A/hat the camera can do in such a context 15 very limited indeed.

Previous page

Previous page